Energy extraction can coexist with native peoples and forests

PASSENGERS arriving on the sole daily flight to the Las Malvinas gas-processing plant by the lower Urubamba river in Peru are ushered into a waiting room and shown a video. This contains a long list of “don’ts” for the Camisea gas project’s 600 permanent workers, including bans on bringing food and having contact with the Amerindian peoples of the surrounding forest. To get on the flight, which is chartered by Pluspetrol, the Argentine firm that operates the gas concession, passengers must have a medical pass, issued only after vaccination against flu and yellow fever.

PASSENGERS arriving on the sole daily flight to the Las Malvinas gas-processing plant by the lower Urubamba river in Peru are ushered into a waiting room and shown a video. This contains a long list of “don’ts” for the Camisea gas project’s 600 permanent workers, including bans on bringing food and having contact with the Amerindian peoples of the surrounding forest. To get on the flight, which is chartered by Pluspetrol, the Argentine firm that operates the gas concession, passengers must have a medical pass, issued only after vaccination against flu and yellow fever.

These conditions embody bitter lessons. Camisea is Peru’s most important source of energy, pumping 1.6 billion cubic feet of gas a day. Since 2004 it has provided the government with more than $6 billion in royalties. Gas from Camisea’s Block 88, which has the biggest probable reserves in the Peruvian Amazon, is sold at a regulated price of $1.80-3.30 per million British thermal units, which has helped fuel Peru’s stellar economic growth of the past dozen years. (By contrast, energy-short Chile imports gas at $8-11 per million Btus.)

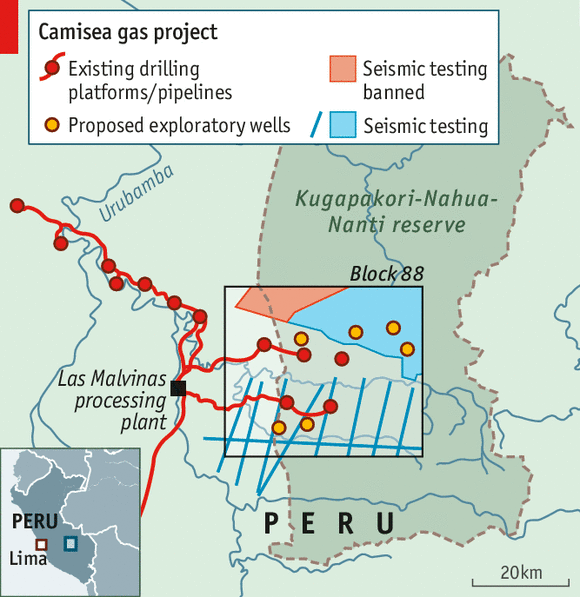

But most of the block lies in the Kugapakori-Nahua-Nanti reserve, created by the government in 1990 to protect Amerindians who have shunned contact with the outside world. Pluspetrol has drawn up plans, approved by the government in January, to conduct seismic tests and develop up to six new well-sites in the block. Foreign NGOs such as Survival International accuse Pluspetrol and the government of threatening the survival of these isolated tribes. “There is a serious risk to people in initial contact,” says Vanessa Cueto of DAR, a Peruvian NGO.

So Camisea has become a test of whether hydrocarbon exploitation can coexist with fragile environments and native peoples. “Camisea is a world environmental hotspot,” admits Germán Jiménez, Pluspetrol’s boss in Peru. In particular it could be a model for Ecuador, which recently agreed to allow oil exploration in the Yasuní national park.

The NGOs cite a dark antecedent: when Shell began exploring Camisea in the 1980s, it built an access road. This was used by illegal loggers, who enslaved isolated Nahua Indians; 300 of them died from diseases to which they had no immunity.

Yet the lessons of that tragedy have been learned. Camisea was developed with a loan from the Inter-American Development Bank, which set rigorous environmental safeguards. Pluspetrol uses an “offshore inland” method for developing the field, as if the forest were an ocean. There are no roads in Block 88: access is by helicopter. Horizontal drilling minimises surface sites. The five well-sites are each no bigger than a couple of football pitches; they are surrounded by dense forest, as your correspondent saw on a flight last month as a guest of Pluspetrol.

Maintenance crews come by helicopter to the remotely operated wells with their dismantled equipment, reassembled on site. They are accompanied by local guides; the company says they have never encountered any isolated Indians. The bright yellow pipelines that carry the gas to Las Malvinas are buried, visible only when they cross watercourses. A scheme funded by the company but run by an NGO employs a small team of Indians as environmental monitors. Cristóbal Rivas, a Machiguenga Indian who is the scheme’s president, says they have investigated small leaks of diesel but that in 11 years there has been no serious impact on the forest.

Peru recently overhauled its laws to incorporate international norms on the rights of indigenous peoples. The government imposed conditions on the expansion, barring seismic testing in the north-west of the block, where there are unconfirmed reports of visits to streams by nomadic Pukirieri Indians, and placing limits on night-working, to avoid interfering with hunting. Pluspetrol will pay $5.8m into a compensation fund for the 850 or so Indians who live in the reserve.

Counting the unknown

This includes about 90 Machiguenga believed to be living in initial contact inside the part of Block 88 that lies in the reserve. Mr Jiménez says that last year, during consultations with the settled Indian communities outside the block, some of the 90 canoed downriver to take part and asked for identity documents so that they could get jobs with the company.

James Anaya, the UN’s special rapporteur on indigenous rights, issued a broadly favourable report last month on the expansion project. He noted that “in many cases” the claims of NGOs are “speculative and imprecise”. But he found that official information on Indians in the reserve was “out of date and incomplete”. He urged the government to complete a study of who might be living in the block, and to organise a consultation with those in initial contact.

The government is hastily doing both these things before work starts on the expansion in June. For some Indians, the work cannot start soon enough. Among those in favour of the expansion is José Dispupidiwa Waxi, the chief of 470 Nahua Indians in the north of the reserve who are classed as being in “initial contact”. Initial contact includes trips to Washington, DC, where Dispupidiwa Waxi has just been to denounce the NGOs that want to block the expansion. The Nahua stand to gain from the compensation fund, which they would spend on more classrooms and a nurse. “We want people to know that we don’t go around naked—we want to be recognised as a settled community,” says Elsa Dispupidiwa, his daughter.

Camisea has changed the lives of the people of the lower Urubamba. “Communities forget their traditional customs,” says Mary Luz Trigoso, a Machiguenga environmental monitor. “The positive thing is that there is work, the children can go to school and there is health provision.” The main complaints are aimed at the local and regional governments, which pocket half the royalties from Camisea; all there is to show for that in the main Machiguenga community is an unfinished secondary school and a 500-metre bog that serves as the main street.

For Peru, the benefits of more cheap gas from Camisea are clear. How to weigh them against the right of, at most, a few hundred indigenous people to live the life they choose is a difficult question. But it is not an impossible one. The Indians “can’t go back, like it or not. History has taken its path and the people too,” says Patricia Balbuena, the deputy minister with responsibility for indigenous peoples. “We have to respect and accompany its process. You can’t say to them, ‘You don’t know what you want’. Tutelage is never positive.”