Harvard grad student Jared Friedman is a designer who is trying to use one of the most precise industrial tools on the planet to produce architectural facades with the earthy charm of your grandmother’s macramé. The budding architect, and his classmates Olga Mesa and Hea Min Kim, were tired of the smooth glass and concrete skins of modern buildings and wanted to create a new architectural style by employing 3-D printing technology.

Harvard grad student Jared Friedman is a designer who is trying to use one of the most precise industrial tools on the planet to produce architectural facades with the earthy charm of your grandmother’s macramé. The budding architect, and his classmates Olga Mesa and Hea Min Kim, were tired of the smooth glass and concrete skins of modern buildings and wanted to create a new architectural style by employing 3-D printing technology.

Low-cost 3-D printers that produce tchotchkes made of melted plastic wouldn’t satisfy Friedman’s architectural ambitions, so he had to build his own machine. “We were tired of seeing the same things over and over being 3-D printed within the design community,” he says. “The scale was always very small due to the size of standard 3-D printing machines and everything relies on a ‘layer upon layer’ process.”

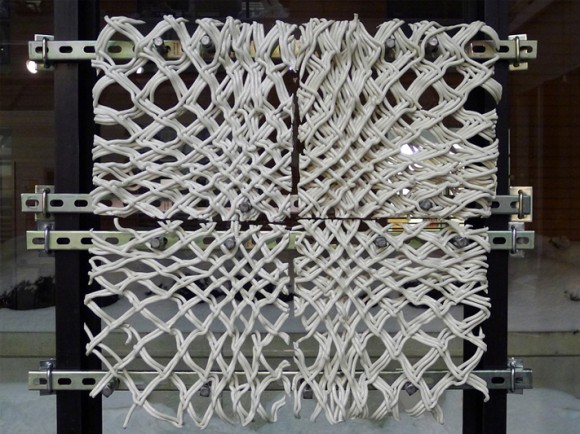

Friedman appropriated a robotic arm from a factory floor and bolted a giant clay-filled syringe to it. He created CAD files that specified paths for the robot to follow and as it progressed clay was squeezed like toothpaste from the metallic cylinder onto an irregular surface forming a two-foot square panel. Half-inch thick clay coils were woven, braided, and built-up in patterns on the panel, but despite their futuristic pedigree they were actually inspired by much older manufacturing processes. “Tools such as the industrial robot can allow for designers to revisit techniques such as weaving, and leverage the abilities granted by the robot to produce new and unique products,” says Friedman. After the pattern was completed the panel’s edges were trimmed, they were fired in a kiln, and assembled on a steel scaffold.

Turning an industrial robot into an artistic tool required fine tuning of the controller software as well as the mixture of clay it extrudes. Friedman’s goal was to create subtle variations in the panels while maintaining tight control at points where the panels would be anchored to the buildings.”The biggest challenges involved striking the right balance between what was controlled and what was uncontrolled,” he says. “We wanted to have enough control to print a panel with a fair degree of accuracy to the initial design, but we also wanted to allow for some of the irregularities to occur that make each panel unique.”

Combining dozens of these panels provides architects with an opportunity to create architectural facades that have the warmth of handwoven fabrics while stretching for hundreds of square feet. Friedman and company have no plans to commercialize their creations, but are excited to have wrung new possibilities out of old hardware.