Lloyd and Noah Graff are in California goofing off this week. This is a favorite column from the magazine archives

by Lloyd Graff

I have never written about my military career, but Robert Strauss’s piece is the impetus forme to come to grips with it in print.

My view of military service was shaped by my father’s war stories. He riveted our family with his stories of World War II, when he desperately fought to stay out of combat. He became a manufacturer of critical aircraft and munitions components in order to avoid getting drafted. In the process he made a considerable sum of money, but staying alive and out of the service was his primary motive. Same for his brother Jerry and partner Aaron Pinkert. Their war was with the draft board, and they sweated every meeting.

They all stayed out because they were doing critical military work. Strictly above board. When I grew up in the 1960s, Vietnam raged. I was sure I was going to be drafted, sent to Southeast Asia and end up dead or in a wheelchair. It was the daily nightmare I lived, and it affected almost everything I did.

After I graduated from college, I went to Law School just to keep my deferment. But as the war was getting hotter and hotter, it appeared that school wasn’t going to hide me forever. I signed up for every Army Reserve and National Guard unit I could find. My dad had some political connections through a Congressman and played that card. Late in 1967, I got the call from the Illinois Guard and reported to Basic Training January 2nd, 1968 at Fort Jackson, outside of Columbia, South Carolina. These were the days of the “Tet Offensive” in Vietnam, the tipping point in the war.

I was the only Guardsman in my training company of 300 men, most of whom would soon face combat. I thought they would hate me because I was probably going home in eighteen weeks, but they didn’t.

About half of the guys in my unit were just out of college and none of them relished going to war. Almost every night we discussed the war with some of the guys weighing the odds of fleeing to Canada, and others trying to figure out the best way to break a leg.

The fellow who had the bunk just beneath me did avoid Vietnam. He was a tough kid from Pittsburgh who fell ill to spiral meningitis. He died in the infirmary during the fourth week of Basic. I had a terrible sore throat that fourth week and wondered if I was coming down with it. I hung in there until I got my first pass and immediately headed for the emergency room at the best hospital in Columbia. The doctor said, “Son, you don’t have meningitis, but that’s one of the worst sore throats I’ve seen. Take this antibiotic and you’ll be fine.” I think I felt better in 24 minutes.

I called CBS News in New York to report the meningitis outbreak. I don’t know if they ever followed up.

I went home to Chicago in May of ’68. Martin Luther King had been murdered in April, and my Guard unit had been mobilized to keep order in Chicago, but I was still at Fort Jackson. I was back on duty for the Democratic Convention in 1968 but the Captain did not put me on the street in Chicago with a bayonet. I stayed back at the Armory writing lesson plans for artillery training, which was never done.

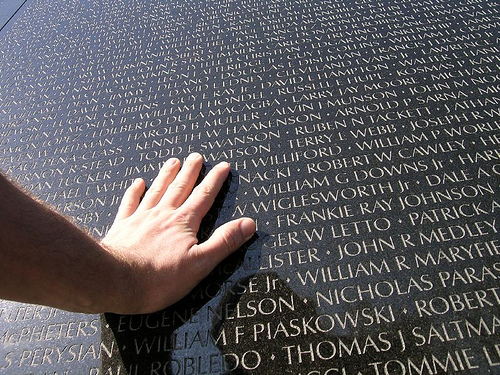

The closest I ever got to Vietnam was the black granite Memorial in Washington. I cried there for the classmates and friends who died in that awful place.

And now we have Iraq, and I’m grateful my boys are not there. And I’ve supported the war and Bush, and I grieve for the men and women who have fallen in the savagery.

I am a draft dodger, son of a draft dodger, with just a little tinge of guilt, yet so grateful to have had a life without having to kill or be killed. I am a soldier who never had to soldier. I am reconciled to never being reconciled to war.