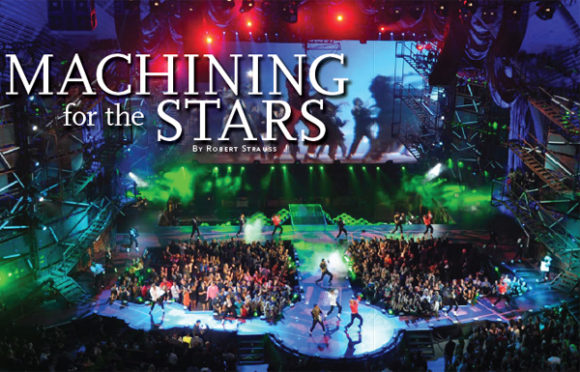

Michael Tait threads his pinky through a loop of fabric on the side of a piece of the stage for Bon Jovi’s “The Circle World Tour.” It’s one of more than 40,000 moving parts that Tait’s company, Tait Towers, has designed and predominantly manufactured for the massive tour stage.

“You think this looks simple, but roadies come in and tell us that this should be up three inches or to the right a bit. We’ve got to be precise, got to get it right,” said Tait, a former roadie and lighting director himself back in the early 1970s for the

band Yes. “We have some of the world’s most demanding customers and they can’t bear to have things screwed up.”

Tait Towers is the premier builder of sets for rock tours and elaborate casino and set shows. It’s a fun business, Tait admits, but it would be nowhere without his sophisticated machine shop filled with CNC machines. His designers and machine operators play the computer keyboards like Rachmaninoff at the piano and most often come up with staging as mellifluous and intricate as any of the great composer’s concertos.

When it isn’t Bon Jovi counting on Tait’s headquarters way out in Pennsylvania’s Dutch country it’s Bruce Springsteen, for whom Tait developed a now-ubiquitous click-and-lock, thus nut-and-boltless connecting system for decking and modular parts.

“This is a business that relies on getting from place to place, mostly on a daily basis,” said Tait. “The easier we can make it to take apart and put together these sets, the more valuable we are. And I have to say that CNC has made our growth, production and our advances really possible.”

Tait studied engineering at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in his native Australia before wandering off to England, entranced by the rock scene. The Clair brothers, owners of a leading audio, video and lighting/design firm, invited him to sleep on their couch when he wanted to devise what was then an elaborate set for Yes. It was circular and cut in pie-shaped pieces so the band could play in the round and, thus, have a bigger audience encircling them.

“But we did it with saws and rulers and whatever passed as modern in the 1970s,” laughed Tait, leaning on his Haas CNC lathe, one of a dozen CNC machines the company uses in its four-building campus. “When one part didn’t fit because it was too wide or not straight enough, we sanded it and did it again.”

“It’s almost laughable now that we have minute tolerances from the CNCs, but you did with what you had back then. Now you can do just amazing stuff without worries,” said Tait.

Teaming up with the Clair brothers, Tait built up his rock staging reputation and soon, like the better mousetrap maker, everyone started beating a path to his remote door in Lititz—ironic because also headquartered in Lititz is Woodstream, the makers of the Victor

mousetrap, the largest-selling trap in the world.

“With Woodstream, our businesses and Wilbur Chocolates and others, we have an amazing workforce here,” said Tait, who employs about 120 workers, almost all hailing from the Lititz/Lancaster area.

One of them is Jared Keim, who at 25 is Tait Towers’ machine shop manager. Keim was an avowed motorhead in high school and didn’t think he would ever go to an academic college. Instead, he headed to Thaddeus Stevens, a local technical school, and discovered that

working with computers and machines was his thing.

“I really didn’t know that Tait was this rock business. It was just a job where

I could use the CNC training I got,” said Keim, talking while squeezing a box on his computer that would display a part for the stage of Lady Gaga’s tour. He showed off a coffin lock, perhaps the most integral part of any rock stage, he said. It comes apart like those Russian dolls-within-dolls, a set of three larger pieces, each containing several smaller metallic and plastic parts. The coffin locks bind together the larger slab parts of the staging—which for Tait usually measure four by eight feet. The coffin locks have both springs to make sure the staging has a little give for the always-bouncing rock stars and, on the outside, a plastic sheathing that keeps it tight as well. Tait laughs and says that in the rock world, that piece is called a “fluffer.” “That’s what they call the woman in porn movies who, well, keeps things rigid,” he said.

It’s CNC technology, said Tait, that keeps things going at Tait Towers, which he said is set to be a $50 million business in 2010.

“When I bought my first Komo 15 years ago people thought I was nuts,” he said. What was the purpose of that? How was I going to make enough use of it?

“In the end, though, rock bands wanted more and more bells and whistles. With those CNCs, we were able to make whatever parts we could design,” he said.

Take the Bon Jovi tour set, for instance. Bon Jovi wanted innovative video as part of his tours. Tait Towers came up with a sort of Venetian blind effect, with doublesided video screens that open and close, expanding from 10-by-10-feet to 10-by-30 feet. When they are closed, crowds see full video 360 degrees around. When they separate, the crowd sees Bon Jovi live.

“As you may imagine, there has to be precise tolerance for all of that,” said Tait. “It is used many times and has to be packed away carefully to go to the next stop. You just couldn’t do that before CNC. We discovered that first, so we got the reputation and the business.”

Back in his Yes days it was a big deal to have two trucks to cart sets around. Now, Tait said, it is not unusual to have 20 trucks carrying a set from a Friday night show in Seattle to a Saturday show in Portland, or wherever. He estimated that the Bon Jovi set Tait is currently working on would need 23 trucks. For the last U2 tour, the group’s elaborate set had to go by plane to its opening show in Barcelona—a cost of $300,000 just to start.

“We are not cheap, at least up front,” said Tait, who would not reveal any particular charges but noted that seven-figure design and

construction costs were the norm. “What we save them in road workers and break-down and put-together costs are immense later on.”

Tait moves his hand along a piece of staging from Metallica’s last tour. The ends are rounded, the connecting parts smooth and with precise tongue-and-groove fits, no bolts are seen. With shipping and tight corners in trucks, he said, jagged corners are intolerable. There are no jigsaws or power drills in rock-roadie hands any more.

“We machine everything as smooth as we can,” he said. In her 2006 tour, Barbara Streisand wanted to come down a long staircase with sparkling railings along the side. Naturally, those railings had to come in pieces, but Streisand was going to slide her hands down them. “Each piece had to fit seamlessly together. Imagine Streisand gasping after she caught her hand on some edge, or if she even looked unsteady. Our machines were able to make it seemless, and have it be taken apart and put back together just as precisely at each stop.” Tait repeated that seamless railing for the Michael Jackson show that never happened because of the singer’s death. It’s not only older singers who need such joints on long, cylindrical items—as is apparent in Britney Spears’ pole-dancing sets or Lady Gaga’s almost-maniacal acts.

Down the road a bit from Tait’s unobtrusive building in the middle of a small industrial park is Tait’s new warehouse. It stores lots of old sets and items that rock groups either don’t want any more or couldn’t store anyway. In a way, it is a sort of rock museum. There are

the spray-foam guns that Tait designed for the Jonas Brothers, Britney Spears’ mainstage decks, Elton John’s piano deck and Springsteen’s video walkway. Each piece still has its sign and coding along the facing, so it could be snapped together again if another date came up—Metallica, the Eagles, Radio City, celebrating the stages of life.

“You could say this is just another boring machine shop, because in some ways it is what anyone would do—have an order and get it done,” he said. “But then these orders are from some of the great artists of our time who know what they want—or at least have cocktail

napkins that say what they want.”

Tait said that his company has thrived, ironically, because the recording business has dived.

“They have to make their money on tours, and thus they want everything newer and newer, but want to know it won’t fail them,” he said. “Our reputation as a machine shop is important. We’re not just pie-in-the-sky, but people who can talk to their tech guys and assure them that it will all go together and come apart, so all [the artists] have to do is play the music and dance.”

Actually, said Tait, few if any musicians come to Lititz. The rock tour business is larger—the design and tech employees outnumber the musicians these days, and that is who Tait deals with. He had lunch with Bette Midler in downtown Lititz once, but he said no one even asked for her autograph.

“The people out here are respectful of your business, and they keep to theirs,” he said. Tait recalls a story that his sound-company friend, Roy Clair, told him about the day Billy Joel came to Clair Brothers to do a little testing.

“He was on the main street in the back of a car and was a bit lost,” said Tait. “He rolled down the window and asked someone where Clair Brothers was. The person said, ‘Oh, I can’t tell you that. They like to be private.’

“This is why I am in Lititz,” said Tait with another Australian chuckle. “Billy Joel, be damned. We are a good machine shop.”

1 Comment

Pingback: Machining for the Stars | Todays Machining World