by Mary Ethridge

Today’s Machining World Archives June 2010 Volume 06 Issue 05

In the shadow of the hulking Goodyear blimp hangar, on a precisely paved and paint-lined hill in south Akron, Ohio, Corbin Bernsen shakes a rolled up sheaf of papers at a dozen of his crew members. It is early April, chilly and windy, and everyone appears tense. They are about to film the first scene of 25 Hill, a family-oriented movie Bernsen was inspired to write after learning last summer in USA Today about the financial trouble and potential demise of the All American Soap Box Derby.

The scene begins but the actor’s words are swallowed by the spring wind. No matter. I know them by heart now.

I would have relished my life’s U-turn at 21, but now, at 51, I find it a little terrifying.

It all started because of a phone call I made last summer to a writer friend of mine at USA Today. I asked her if someone there would be interested in writing a story about the Derby’s financial problems. Someone was and did. Corbin Bernsen read it, and seven months later I’m helping the Hollywood actor produce the movie he says will unify Akron and help save the Derby.

I knew who Bernsen was, of course. I’m a fan of Psych, the USA Network’s longest-running original series in which the now-nearly bald Bernsen plays the main character’s father. I remember him best in those bespoke double-breasted suits as the handsome womanizer Arne Becker in the 1990s hit, L.A. Law. He’s beloved in Northeast Ohio for his role as the Cleveland Indians’ fussy third baseman Roger Dorn in Major League.

Until late last summer, I hadn’t had much to do with the Soap Box Derby, which has been headquartered in my hometown of Akron, Ohio, since 1933. As a writer for the Akron Beacon Journal for 18 years, I’d covered some of its events on occasion. And one of my personal claims to fame is that I went to high school in New Hampshire with a cousin of the Derby racer who cheated in 1972.

But last summer when I heard the Derby was heading into its third year without a title sponsor and falling deeper into debt, I felt surprisingly indignant. My civic pride was insulted. The Derby may be seen as old-fashioned by some people, a little hokey perhaps or too slow-moving in these days of turbo tweeting techies, but it has been ours—Akron’s—for decades, and it is a very good thing.

To build a Derby car—which is powered only by gravity—children work closely with an adult, usually a patient parent. During that one-on-one time, the garage becomes a place where things that might not be said otherwise are said. The children learn about math, physics, communication, teamwork and the vital lesson that if you hope to win; you have to finish what you start.

I couldn’t believe a corporation wouldn’t step up to support such a rare program. It just seems like a no-brainer for a marketing team: spend $250,000—pocket change in the multi-million dollar sponsorship world—help kids, and be associated with a wholesome bit of Americana with a 75-year legacy. Beyond that, racers come from 150 cities in 43 states and seven countries. Although its image may be local-yokel, Fourth of July and Main Street USA, its reality is far more than that. The All American Soap Box Derby is a year-round effort that requires a paid staff of engineers, machinists, marketers, secretaries and maintenance workers, as well as a board of directors, to steer it. In the spring and summer race season, its volunteers number in the thousands.

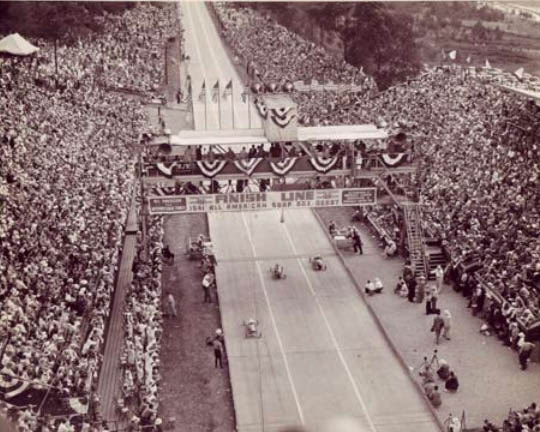

Chevrolet sponsored the All American Soap Box Derby from 1936 to 1972. In the Derby’s heyday in the 1950s, Chevrolet spent millions of dollars sponsoring and marketing the race. Chevrolet’s presence attracted smaller sponsors as well as plenty of Hollywood glamour. Celebrities including then-actor Ronald Reagan, Rock Hudson, Evel Knievel and O.J. Simpson came to mingle with corporate executives and fans. The late actor Jimmy Stewart attended six times.

Back then, crowds numbered in the 60,000s, compared to the 15,000 who’ve come in recent years. Despite the financial troubles of the Derby, it’s more popular than ever among young people. In 1975, about 100 competed in the championship race in Akron. Last year a record 603 did, although that includes a new Ultimate Racing League for competitors 18-21. (Standard races are for children 7-17.)

When I met Bernsen, he expressed other reasons to save the All American Soap Box Derby. The United States is a relatively young country, said Bernsen, and we must preserve those few traditions that have become part of the fabric of the nation. As something that sprouted from a unique time in the nation’s history—the Great Depression—the Soap Box Derby certainly qualifies as a living piece of America’s heritage. Although it has remained the same at its core, the derby has also changed with the times as its tricked-out cars attest; its history is ours. In this time of war, Bernsen believes, the American-grown Derby provides a patriotic rallying point for the country’s declared and instinctive values of family, faith and freedom.

Sadly, the world of corporate sponsorship has changed drastically, according to Roger Rydell, a public relations executive with Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. and a new member of the Derby board.

“Corporations are looking for return on investment,” Rydell told the Wall Street Journal in a recent story about 25 Hill. “It could be that the metrics associated with that return have become a little more mercenary than in the past.”Nevertheless, I expressed my outrage to William Evans, president of the board of the Soap Box Derby. Knowing of my media background, Evans asked if I could help get the word out nationally that the Derby needed help. That’s when I called the columnist friend at USA Today, and she passed it on to her colleague, marketing writer Bruce Horovitz. In early September, USA Today published Horovitz’s story that outlined the seriousness of the Derby’s financial trouble and its efforts to modernize itself without a pile of cash.

The Derby had lost money four out of the past five years and was, according to Horovitz, “living hand to mouth.” It owed its lender, Akron-based FirstMerit Bank, more than $500,000. It had been making interest-only payments on its loan some months and the bank had cut the line of credit the Derby uses to buy materials to make car kits—a primary source of revenue. If the Derby didn’t get help soon, Horovitz wrote, it would be bankrupt within months. Our hope with the USA Today story was to attract a new national sponsor. What we got was Corbin Bernsen.

As Bernsen tells it, he had nothing to read on that September afternoon as he was stuck on a plane stranded on a tarmac. He grabbed a discarded USA Today from a nearby seat pocket and read about the Derby’s woes.

He felt so upset about the possibility of losing an American tradition; he decided to write a screenplay about it. Seven weeks later, screenplay done, he wanted to come to the Derby’s racetrack, Derby Downs, to see the place for himself.

At the Derby Downs office, Evans, Huntsman and I listened as Bernsen outlined the story for us, which incorporates the real-life troubles of the Derby. In the film, the Derby dreams of 11-year-old Trey Caldwell are threatened, first when his father is killed fighting in Afghanistan, and then when the Derby is shut down because of money troubles. Nathan Gamble, a 12-year-old whose credits include major studio films Marley & Me and The Dark Knight plays Trey. Tim Omundson, who stars with Bernsen on Psych, plays Trey’s father. Through the efforts of Trey and his peers the Derby is eventually saved.

Bernsen then told us he needed about $1 million to make the movie. He envisioned 40 investors at $25,000 each. Then, he turned his intense, blue-eyed gaze on me. “Mary, do 40 people in Akron have $25,000?” he asked. I felt the color leave my face; I could sense what was coming. Rather than turning to his usual Hollywood sources, Bernsen said, he wanted 25 Hill to be an Akron movie—funded and made possible by the people of the community that has nurtured the Derby all these decades. “If I went to L.A. for funding, they’d have only the bottom line in mind. They’d want to make it where and how it would be least expensive,” said Bernsen. “But if the project is funded by the Akron area, then it’s Akron’s movie, not L.A.’s.”

I told him that yes, more than 40 people in Akron had $25,000, but getting them to part with it to invest in a movie would be a challenge.

“Well, let’s do it, Mary. Get me a dozen or so of these people in room and we’ll just talk and I’ll tell them what I have in mind,” Bernsen told me. I wanted to run and hide but I just nodded. I knew what we were in for. Akron is a conservative community that is willing to change, but changes very slowly. Filmmaking is about as far out of Akron’s realm as tire building is out of Hollywood’s.

Two weeks later, I managed to gather a group of wealthy community leaders to listen to Bernsen speak about the Derby and the proposed movie. He gave a speech I would hear over and over, in various forms.

“Computers and televisions are great. Nothing wrong with them, but that’s not all there is to the world. Every kid has the instinct to put wheels on a piece of wood and make it go, and we need to nurture that kind of creative thinking,” Bernsen said. The Soap Box Derby is also a way of life. It’s about families coming together to make something with their hearts and hands.

“It’s spirited competition rooted in community and innovation,” Bernsen said. “We just can’t lose that. If the Derby disappears, the world won’t fall apart, but what will go next?”

Two weeks later, Corbin made the presentation to another group I put together, and two weeks later to another. After four visits to Akron, Bernsen didn’t have one check in the account for 25 Hill Akron Filmworks, the LLC we set up for the investments.

There were two primary obstacles. People wanted the Derby fixed first; then we could talk about a movie. Bernsen explained to those people that a movie would bring thousands of new “eyeballs” to the Derby, which meant a higher profile, a better chance at sponsorship and more awareness among kids. Also, potential investors had little idea how an independent movie makes money and seemed skeptical that they do. They were also tired of throwing money down Akron’s gaping booster hole. After awhile the good feelings run out.

So Bernsen gave them a mini-lesson in film industry finance, dancing painfully around statements that might get him in trouble with the Ohio Securities Commission. He talked about a “typical” independent film of the sort he wanted to make. Such films, he said, can possibly double or triple an investment over a period of 30 to 36 months, a relatively long lag time because of the post-production work that needs to be done on such a “typical” film as well as the hashing out of agreements with distributors.

Long gone are the days when movies went automatically to the theater; long gone even are the days when going straight to DVD was seen as the mark of schlock. The marketing costs associated with putting a movie in theaters across the country are so enormous now, in part because of the skyrocketing number of advertising outlets (millions of Web sites; thousands of cable stations), that even if a film does well at the box office, it may lose money for investors. Today, we can get our movie from a vending machine, on our computer, at the video store or straight from our cable company in addition to seeing it at a theater.

In a late night phone call with Bernsen—and there were dozens—he told me he’d never done anything so difficult in his life. It took two months and a lot of ups and downs to get our first check. It came from someone who wasn’t even at any of our meet-and-greets with Akron leaders and Bernsen.

An architect in an Akron suburb had happy memories of the Derby from his childhood in the 1940s and 1950s. He’d heard about the project and thought it would be “fun” to invest in it. Where were more of those people? How could I find them?

Looking back, I think I turned to the obvious choices first to find investors, which meant I was mining a tired, compassion-fatigued lot. And although we did get support from some of those traditional Akron leaders, most of the money came from sources that surprised me or of whom I’d never heard—mainly doctors, lawyers and other professionals whose names aren’t found on city buildings. These were primarily average upscale Joes, not the Fortune 500 executives and medium-sized business owners I expected. As this issue goes to press in June, we’re still seeking a few investors so we can finish up the movie the way Bernsen envisions. The filming for 25 Hill is scheduled to finish on July 24, at the real-life International Championship of the All American Soap Box Derby.

The Derby is also faring better financially. In December, Akron-based FirstMerit Bank, which held the Derby’s loan, sued the Derby for the $623,000 it was owed. It looked more and more like the Derby would be put on the auction block. But within weeks, the City of Akron stepped in with a plan to back the Derby’s loan, and the bank set up new, more favorable terms.

If the Derby failed, Akron would have to take over the $42,000 annual principal payments, which the city pointed out are less than the $60,000 a year the city has been giving the nonprofit.

“The last thing we want to see is Derby cars coasting down the hill in another city,” Akron Councilman Mike Freeman told the Beacon Journal. The Greater Akron Chamber agreed to help with a business plan and fundraising. The Derby board was remade to include more members of the corporate community, including representatives from Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. and FedEx Custom Critical.

One thing hasn’t changed since the Derby’s early days: “You’re going to Akron,” are the sweetest words a soap box racer can hear. Having lived in Akron most of my life, I’ve suffered through every Rust Belt, Rubber and Dacron joke imaginable. It’s a bit startling and wonderful to hear my hometown’s name said with such reverence and longing.

That, to me, is a reason to save the All American Soap Box Derby.

There are plenty of them, just ask me. And bring your checkbook.

5 Comments

This article is a masterpiece, and thank you for writing it, and being involved with the derby and the movie. I am a secretary at Springfield High School, where the first scenes were shot. I’m hoping to get out to be an extra when the crew returns to shoot in Green. It totally amazes me that Summit Racing in Tallmadge has not stepped up to the plate for sponsorship, or took over as the MAIN backers.

I was the Director of the Troy, Ohio, Soap Box Derby in the late 60’s. Our race was run by our local Optimist Club. My year, our largest, we had over a 100 kids. We ran a tight race. We made sure our kids built their cars. Consequencely, one of our kids was never going to win the All American because too many of the cars that won there were built in shops, not Johnny’s dad’s garage.

Too many parents who want to win at any expense ruined the All American Soap Box Derby. It’s the same old story. Ask any coach what their biggest headache is and he or she will say one or perhaps several of their kids parents.

The premise is great. Let Dad and Johnny spend some time together, planning the car, teaching Johnny how to use tools and make something with his hands. The car is his creation. And frankly it should look like a kid built it. Even so, it’s something he made and something he can be proud of. I saw a lot of disapointed boys when they saw the professionally made cars they had to race at Akron. I suspect the kits help level the field in later years.

I’m a parent and a grandparent…let’s let kids be kids. Let’s not teach them that winning is everything even if you have to bend the rules. The rule bending became so obvious at the All American that it lost its credibility. There’s a lesson in there, but those that need that lesson will never see it. That’s too bad. The kids are the big losers.

You brought a lot of old memories. From the chevy dealership to the friends of two brothers I helped build 2 cars.

I’m looking foreward to seeing this movie!

Knowing I have a fine early original photo of Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth presenting a Soap Box Derby Championship Trophy to a teen at Cleveland Stadium and Tris Speaker & Chris McAllister of Chevrolet looking on, I would like to know the value of this item. I became very excided to learn that a movie had been produced dedicated to the thrilling life of Soap Box Derby Kids & Fans. This is wonderful! We can’t wait to see it!

I have a 1937 soap box derby trophy, my father won the first soap box derby race in Charleston WV. Ive had it all these years but the wood base is missing. I would like to see a picture of one. so I can make one or get it restored. Any enfo would be welcomed.