Today’s Machining World Archives September 2006 Volume 02 Issue 09

As testimonials go, it is hardly the usual.

“I spray WD-40 on the hinges of my cooler so I can sneak a beer in the middle of the night,” claims Kevin Meany, identified as a “school district mechanic/volunteer fire chief.”

Even in these days of “Dr. Z,” the voice of the Daimler-Chrysler chief touting his cars somewhat humorously and the return of the “speecy-spicy meatball” commercials for Alka-Seltzer, the website for the WD-40 Fan Club is a bit goofy. There you find not only the above Mr. Meany, but also six other folks who comprise the alleged “WD-40 Fan Club Board of Directors.”

“It’s not like they ever meet or anything. It is just for fun. They don’t talk to the press,” said Jesse Lovejoy, a spokesman for the company. “We just like to have fun here.” What is not to be fun when you have a product with an odd name and, so the company claims, an 80% penetration rate.

“That means that 80% of homes have around or have used WD-40,” said Tim Lesmeister, the WD-40 vice president for marketing. “We have got to believe that even Coca Cola doesn’t have that kind of penetration. There are at least other colas. When you think of the kinds of things this product does, WD-40 is what you think of.”

The legend of WD-40 is somewhat similar to that of Tang, which allegedly was developed so those early astronauts like Scott Carpenter and John Glenn had something to drink while orbiting the Earth while Walter Cronkite sang their praises. It is one of those post-World War II sagas worthy of a Norman Rockwell cover and a “Saturday Evening Post” story.

The aerospace industry was centered in Southern California in the late 1940s and early 1950s for many of the same reasons the movie business nested there a generation before. There was a lot of room to build big plants for what were presumed to be huge planes and missiles and, frankly, the weather was good year-round to attract employees. It is true that there were a bunch of naval bases, Army camps and Air Force installations in California, but the real attraction was land and weather – presumably aircraft performed better in a long dry summer season. And, workers might perform better if they knew in their off-hours they could easily get to the luscious Pacific Ocean waters.

The problem was that when aerospace companies built their plants too close to the ocean, the damp air started to corrode the parts of the new planes and missiles.

Still, the new industry not only attracted pilots, factory workers and marketing folks, but also dreamers and inventors willing to solve these kinds of problems. Three of those research types at the San Diego Rocket Chemical Company came up with a formula in 1953 that they thought would inhibit such corrosion. They had tried 39 times to find a solvent that would both degrease those parts and then provide a rust inhibitor that would stand up to that damp ocean air.

On the 40th time, though, the water displacement solvent did what it was supposed to do: ergo, W D, as in “water displacement,” and 40, as in “the 40th try.” It was like Chanel’s famous No. 5. No one cares what the first 4 were, just like no one in the machine industry – or in any of those 80% of American households – gives a hoot about the first 39 formulas.

“Everyone, I think, is just happy the researchers didn’t give up at, say, 25,” said company marketing guru Lesmeister. “It is one of the world’s great products.”

The first big contractor to use the product was Convair (later a division of General Dynamics Corp.), which was making the Atlas missile, which soon became the most important missile in the United States arsenal. With its inflated steel tank style, the Atlas had, and still has, the lowest empty weight ratio of any missile without a reliability penalty.

Eventually, Convair’s employees discovered the wonders of WD-40 for personal use. They started spiriting the cans home from the plant. They found out it could do, well, most anything. They could clean and protect their tools with it; lubricate their lawnmowers and their new suburban kitchen items, too. It loosened bolts and nuts and degreased the kids’ bicycles. Heck, it sometimes even degreased the kids.

In 1958, the bosses at Rocket found out about the inhouse smuggling at Convair and decided to make lemonade out of lemons. They put WD-40 in aerosol cans and hired a few salesmen to get it into local hardware stores. According to a company history, by 1960, they were selling 45 cases of the stuff a day.

Then Hurricane Carla hit the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. In order to help rebuild, contractors from Texas to the Florida Panhandle needed all sorts of everything. They had heard of this semi-miracle product from San Diego and got a truckload sent out. The cult had finally spread east, and through the 1960s, the aerosol can with the funny name became ubiquitous in carpentry and machine shops and on construction sites. By 1969, with only one product, albeit a good one, in its line, the Rocket Chemical Company offcially became the WD-40 Company, four years later going public.

Now more than one million cans of WD-40 are sold each year, and annual revenues top $150 million.

Adding to its mystique, like with Coke and Pepsi colas, is the secret nature of WD-40’s formula. Company officials say there are only four people who really know the formula and only a couple who deal with it day to day.

“There is one guy who is part of WD-40 who gets up every morning and makes the brew,” said marketing chief Lesmeister. “We have three locations (in Sydney, London and San Diego) that make the secret sauce, but primarily it is made in the same warehouse in San Diego that has been there for many years. He does have a back-up or two, but even the CEO doesn’t have anything to do with making it. In fact, almost no one here knows whether it is something really complicated or really simple.”

Garry Ridge, who has been CEO of WD-40 since 1997, plays along with cult status. On the fi ftieth anniversary of the company, he rode into Times Square in a suit of armor, carrying the secret formula. On the other hand, he doesn’t want the company to stand too pat. He told the Wall Street Journal earlier this year that more people used WD-40 in a year than used dental floss, but worried that the future wouldn’t always look like the present.

“We decided we were going to be in the squeak, smell and dirt business,” he told The Journal. “I felt that there would always be squeaks. There will always be smells. And there would always be dirt. That was the strategy as we started looking for brands that we could acquire.”

So now the company owns products like 2000 Flushes®, the X-14® cleaner line, the Lava® line and 3-In-One® dry lube.

Still, the bulk of the business, and the fun, comes from WD-40. Even Consumers Union, that tough-minded find-faultwith-most-anything group, touts WD-40 on its Consumer Reports 4 Kids recommendation page, saying it is marvelous for removing decals and stickers.

The WD-40 Fan Club came about, according to Lesmeister, after people started emailing oddball uses for the product. Now the company website lists more than 2,000 uses for WD-40, from the mundane and predictable (“Keeps garden tools rustfree”), to the sensual (“Loosens crud around stoppers on antique perfume bottles”) to the just plain nutty (“Removes stains left from Silly String”).

The company even did a poll to ask residents of each state what the best use for WD-40 would be for their states. In Pennsylvania, for instance, it was to keep the Liberty Bell from squeaking, while in Kansas, it was “lubricates breakaway rims for easier slam-dunking by the Jayhawks.”

What is even more amazing is that competitors rarely speak ill of the product.

“We’re a good lubricant and at least its [WD-40’s] equal in corrosion protection,” said Gary Nieberle, the product manager for 3-36, the top-line similar product for CRC, the Warminster, PA-based company. “But I would never knock WD-40. We like our product better, but theirs is also good.”

About the only thing consumer watch groups do criticize WD-40 for is its flammability, which the company certainly acknowledges.

“But I think people are careful of that. Every product has to have some minor downside, but we have never had any problems with that,” said Lesmeister.

Lesmeister even gets a good chuckle when oddball stories, even seemingly negative ones, come out about WD-40.

Last year, for instance, police in England started to use WD-40 to thwart cocaine users. In Avon, Somerset and Bristol, cops started spraying toilet seats in pubs with WD-40 after figuring out that, first, lots of coke was being snorted there, and, second, the WD-40 made the stuff congeal. Then, when people would try to snort it, the mixture of WD-40 and cocaine would inevitably cause nosebleeds,

and the subjects would be caught, if not red-handed, at least red-nostriled.

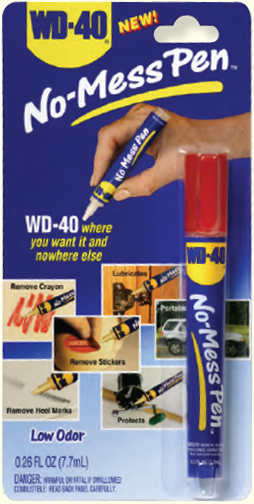

Recently, the company has decided to branch out just a little bit in getting WD-40 in cracks and crevices that had eluded it. There is a new super-sized can, the 18-ounce Big Blast, mostly for big machine-shop or automotive bay use. On the other end, there is the WD-40 No-Mess Pen, a felt-tip marker-like dispenser for tight applications.

“We got it out this way to people who hadn’t used it before, specifically women, and into crafts and hobby shops, and places like Office Depot, another vehicle for distribution,” said Lesmeister.

“I guess the motto here is we won’t rest until everyone is using WD-40, for something, all at once,” he said with a chuckle. “It may not be so far-fetched.”

4 Comments

If you are looking for another story about a successful company with a unique product that’s been around for a while, check out our web site. Bearing Buddy is a product that was invented in the 1960’s to solve a particular problem and has been used in other unique applications due to the creativity of people in other fields.

SInce most oils floats on water it took a while to find a oil that would displace water. Fish don’t float so guess what oil they tried.

You might want to look further at a disease called Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Disease of Bone Marrow Blood Cells, which is caused by exposure to benzene, a component of WD-40. You may find that there is a class-action lawsuit against this common product alleged to have caused the disease in many people who have used the stuff.

How does a company get an 80% penetration rate in the US and $150 million in revenue by selling only 1 million cans a year?

“Now more than one million cans of WD-40 are sold each year, and annual revenues top $150 million.”