Today’s Machining World Archives March 2011 Volume 07 Issue 02

By Bridget Mintz Testa

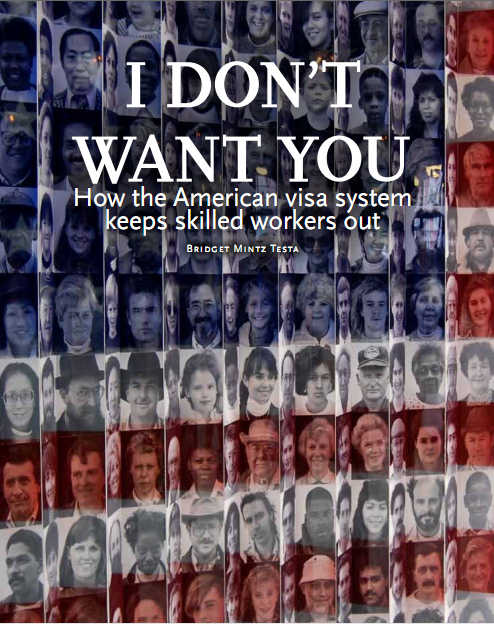

Although the nation-wide shortage of workers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (the “STEM” fields) is well-known, the comparable and equally critical shortage of skilled workers in fields like manufacturing has hardly been publicized at all.

Most efforts by American industry, including those specific to machining, have focused on improving programs and training for young adults; even trying to grab the interest of students as young as 12 or 13 to entice them into a career in the skilled trades. Despite these efforts, nobody knows if the U.S. will produce enough skilled laborers to support the manufacturing sector in the coming years.

Unlike in the STEM fields, there have been few government- sponsored visa programs to bring skilled trade workers to the U.S.—so the affected industries have been left to solve the problem by themselves. One part of the solution to the skilled labor shortage could be to hire skilled trades-people from Europe’s strong apprenticeship system and bring them into local machine shops. But how does a shop go about doing this, and is it worth the time and cost? These questions bring up the role legal immigration could play in supplying the necessary amount of talent to support the U.S. manufacturing industry in the coming years.

An intro to the U.S. visa system

Each year the U.S. makes available 140,000 employment related visas that can lead to permanent residency by awarding a permanent resident card, or “green card,” and 65,000 H-1B visas, which are strictly employment-related and have an expiration date. Another 225,000 family-related “green cards” are also issued annually, but these have nothing to do with employment. All “green cards” are permanent, although they sometimes have conditions and must be renewed periodically, like drivers’ licenses. Employment related visas are issued based on the applicants’ education level, and there are multi-year backlogs to get one, said William A. Stock, an attorney specializing in business immigration with the Philadelphia law firm Klasko, Rulon, Stock & Seltzer, LLP.

The H-1B visa, which is good for six years, is one of an alphabet soup of temporary visas that companies can use to sponsor foreign nationals to come and work in the U.S. Other visas used for this purpose include the H-2A, H-2B, L and E visas. H-1Bs are different from the other temporary visas in that someone in the U.S. with one is eligible to apply for permanent residency.

The recession lessens demand for workers from abroad

For fiscal years 2007 and 2008, all 65,000 H1-B visas were taken by the end of the first day they were made available, said Lynn Shotwell, executive director of the American Council on International Personnel. ACIP is an organization of U.S.-headquartered companies from all industries with more than 500 employees that have an interest in employment immigration.

Since the recession began, it takes as many as six to eight months for all H-1B visas to be taken. Companies are now able to hire from within our borders because of the surplus of American workers available. For fiscal year 2011, it took from April 1, 2010, until January 26, 2011, for all 65,000 H-1B visas to be taken. No more applications can be accepted until April 1, when the 2012 visas become available. In any year, after they receive their H-1B visas, recipients can’t start work until the following October 1. So individuals who received visas on April 1, 2010, are eligible to start working on October 1, 2011.

Unlike these temporary visas, “green cards” award permanent residency and the right to work in the U.S. on the same terms as a citizen. “The normal “green card” process takes two to 10 years,” Stock said, “but it can take more. The higher the level the job is, the faster the “green card” will be issued.” With jobs requiring only a bachelor’s degree getting a “green card” can take six to 10 years.

Who gets first dibs?

“The 140,000 employment-related visas (‘green cards’) issued every year go first to highly educated people, such as scientists, authors, corporate executives—known as the ‘first call’ people,” Stock said. “Forty-thousand of these visas are reserved for ‘first call’ people.”

The “second call” category is made up of doctors and lawyer types, “those at a master’s degree level or above,” Stock said. Another 40,000 visas are reserved for this category. The third level includes everyone else—those with only bachelor’s degrees and skilled and unskilled labor, he said.

The problem is that in practice the categories aren’t clear. Because so many people are interested in working in the U.S., there is a lot of spillover from one level to another. There may be 60,000 people in the “first call” category, so 20,000 of them spill over to the “second call” level, which means they get priority. Now there are only 20,000 “second call” visas left that year, and perhaps 60,000 applicants in that category as well. This group gets the remaining “second call” visas and all the remaining category three visas, too.

It can take years

On top of the spillover problem, there’s an enormous backlog. “In 2000, 2002 and 2003, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (now the USCIS) didn’t process half the visas,” Stock said. “In 2007, the State Department and USCIS had a feud over visas. The State Department told the USCIS to process all new applications as though there were no backlog.”

Today, there’s a backlog of more than 100,000 visas being worked on at a rate of 140,000 visas per year. But that doesn’t count new visa applications coming in. “Every year is the same—they start at the top and work down in terms of skills,” Stock said. That is, it’s not first in, first out. It doesn’t matter how long your application has been on file; what matters is whether you’re in the “first call,” “second call” or “third call” group. “So the immigration process [can] take 10 years,” Stock said. “Unskilled workers can’t get in at all, and the laws don’t work for skilled labor, like machinists, either.”

An option for the well educated

H-1B visas can only be used for jobs that require a college degree, and the people who get H-1B visas must have a degree related to their profession to get the visa. “My American Council on International Personnel (ACIP) members are spread across all industries, and they’re hiring people with a minimum of a bachelor’s degree,” Shotwell said. “Frequently, they’re hiring people with higher educational levels.” And when Shotwell’s members are hiring via H-1B visas, they use them as a way to allow the person to work here while they wait on a “green card.”

“When our members are recruiting at college campuses in the United States, they find that more than half of the graduates in science, technology, engineering and math are foreign nationals—especially in the advanced degrees,” Shotwell says. “So they have to use the visa system to hire these people.”

Little help for the skilled trades

There are some visas available for trade positions, but they don’t help machining companies or other industries trying to recruit skilled labor. H-2A visas are specific to agricultural workers, only last for about nine months, and can’t be renewed. H-2B visas could be used for machinists, but like the H-2A visas, they only last for nine months and can’t be renewed. Additionally, both the H-2A and H-2B visas take so long to get that by the time the sponsored employee arrives, your need for them may have passed.

Strangely enough, there are two visas, the L and E visas, available strictly for companies based outside the U.S. but with facilities on U.S. soil, or for U.S. companies that have foreign facilities. But these visas are good for just a few months and focus on special projects. They too can take a ridiculous amount of time to process. “It may take an employer anywhere from three to five months to get H-2A and H2–B visas, and four to eight weeks for L and E visas,” said business immigration attorney William Stock.

You said, how much?

Besides the hassle and time commitment of working through the USCIS system, another deterrent for companies trying to hire from out of the country is the cost. It takes several thousand dollars to obtain an H-1B visa, including the legal costs. “The legal fees to hire someone on an H-1B visa and then get them a “green card” can run more than $30, 000,” Shotwell said.

Training at home

Ted Toth, president of the third-generation family-owned firm, Toth Technologies, and secretary-elect for the National Tooling and Manufacturing Association’s (NTMA) 2011 board of directors, started the organization’s Precision Jobs for American Manufacturing program and ran it for four years. “It’s a means of supporting training centers,” Toth said. “It helps support recruitment and training of manufacturing, placement and retention of employees, and how to build a good advisory board. We want to start recruiting in elementary school,” he says. Toth also mentioned the NTMA’s National Robotics League’s competitions as a strong recruitment device, and Toth Technologies is currently sponsoring a student in community college.

Roger Sustar, president of precision manufacturing company Fredon Corporation in Mentor, Ohio, started sponsoring high school and vocational students in 1992 to build annons so they could learn machining skills. Sustar has hired about 350 “graduates” of the Cannon program since its start. It is a feeder system for Fredon.

Just last year, the northeast Ohio Alliance for Working Together, also initiated by Sustar, partnered with Lakeland Community College to develop a two-year manufacturing associate degree. It’s intended to help address the area’s projected need for 60,000 skilled workers in the next 10 years.

For the long-term, Sustar foresees no machinist shortage for his company or community thanks to the Cannons of Fredon and the Lakeland Community College programs. “For my company there is no shortage because I work hard on it with the local community,” he said. “The community college system will feed the community. These kids are our future.”

Where the system stands now

Even with the efforts of people like Sustar, the number of people graduating with the skills to work in machining is not enough. And it doesn’t seem like visa sponsorship programs or legal work-based immigration will be able to fill in the gap any time soon. Neither of the two pieces of legislation that address immigration reform, the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2010 nor the DREAM Act, were passed in the last Congressional session. That means efforts to craft bi-partisan, far-reaching immigration reform starts all over again with the new Congress.

The new Congress’ first effort concerning immigration was a hearing convened on January 26, by the House Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement. Its goal was to determine whether the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s worksite verification practices were strict enough. This is what is known as an “enforcement only” solution, but in no way does it address actual immigration reform. In lieu of such reform, industries that need trained, skilled labor are still on their own.

Immigration Reform Today

Many proposals have been made to fix the U.S.’s broken im-migration laws. Last September, Senators Robert Menendez (D-NY) and Patrick Leahy (D-VT) introduced the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2010. The bill included demands from both Republicans and Democrats concerning employment visa systems, a legalization plan for undocumented aliens, and mandatory employment verification.

Many proposals have been made to fix the U.S.’s broken im-migration laws. Last September, Senators Robert Menendez (D-NY) and Patrick Leahy (D-VT) introduced the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2010. The bill included demands from both Republicans and Democrats concerning employment visa systems, a legalization plan for undocumented aliens, and mandatory employment verification.

In December, Senate Majority Leader, Harry Reid (D-NV), and Majority Whip, Dick Durbin (D-IL), introduced a new version of the DREAM Act, which would have given legal status to undocumented aliens who were brought to the U.S. as children, grew up there, did well in school, and wish to attend college or join the U.S. military.

There are so many stakeholders in the immigration debates, and they can’t agree,” says H. Robert Sakaniwa, associate director of advocacy for the American Immigration Lawyers Association. Truly comprehensive immigration reform must address legalization of undocumented aliens. As long as the anti-amnesty champions focus on preventing any change in that one issue, no immigration reform can succeed.

There is a whole faction that is totally opposed to providing legal status to those who are currently undocumented,” Sakaniwa says. “They will work hard to stop anything with this type of reform from moving. Even if they support business im-migration reforms, their priority is to prevent the creation of a path to legalized status for those who are here now. [They will do that] at the expense of the other reforms they support.”

2 Comments

I have read about companies doing OJT with apprentice programs. With all the American people out of work, crying that not enough foreigners can come in is BULL_____.

Manufacturing should link up with unemployment benefits to recruit people to train. I know they’re out there. Most people would rather work than collect.

Good article. I have a very tough time trying to find good experienced skilled technical people. Its not just about finding people. Its about finding good people with a strong work ethic. Lets face it, many long term unemployed are voluntarily unemployed. People with good skills and work ethic are already working. I rather hire an eager foreigner than train someone who thinks they are entitled to a job. We need to ask ourselves, why do foreigners have such good work ethic?