Responding to customer demands

Globalization. Whether you hate it or not, it’s dramatically changed the way business in the United States and elsewhere is done. Initially, only Fortune 500 companies were big enough to play in the global environment. Although they started about 10 years later than large companies did, small and medium-sized businesses eventually went global, too. Now, even companies with fewer than 10 employees, like Central Screw Products of Detroit, Michigan, can have a big international presence.

Central Screw Products went global in response to customer demands, but the experience gave it many more advantages than just cheap labor. Houston-based Tech-Seal International, founded and owned by Mark Adamson, went global for other reasons. For both companies, the experience taught them a lot and changed their businesses in many ways.

Going abroad to expand capabilities

Banks’ current reluctance to lend capital to businesses is nothing new to Mark Adamson, founder and owner of Tech-Seal International in Houston. After starting his company in 1989, Adamson wanted to expand. “The banks wouldn’t buy me a Coke, much less anything else,” Adamson says. “I couldn’t afford the $400,000 to $500,000 I needed to buy a machine, so I decided to go overseas.”

On the advice of Michael Mai, a friend Adamson had met before opening his Houston shop, he tried China first. Adamson wanted to eventually create his own products, but the Chinese factory was only interested in mass production. So Mai, a Vietnamese national, suggested his home country.

The two of them, partners by then, went to the Southeast Asian nation in 1992. Two years later, they started manufacturing commodity oil and gas industry parts in Ho Chi Minh City. Mai stayed in Vietnam to manage the operation.

“We bought manual machines on credit cards and used cheap labor to run them,” Adamson says. “I’d wire Michael $1,500 or $2,000 at a time, and he’d buy more machines.”

Headaches of doing business in Vietnam

In 1995, Adamson and Mai left the first location and built a facility in Lam Dong Province, about four hours northeast of Ho Chi Minh City. Adamson didn’t have his own products yet, so this new facility was also initially for commodity oil and gas parts.

There, Adamson and Mai ran into one of the perils of doing business in Asia-corruption. “There is a lot of bribery,” says David James, president of Business Strategies International in San Francisco, a consulting firm for American businesses that want to establish operations abroad.

United States law prohibits citizens from bribing foreign government officials, but James says, “In most Asian countries, things don’t get done without acknowledging that favors are being asked. It may look like bribery, but it is the way things get done.”

In Adamson’s case, the problem wasn’t outright bribery. “If you want to get your electricity hooked up, you can always get it done faster [by paying someone a bribe],” Adamson says. “But I don’t do that, because they always come back for more.” Beyond the hook-up issue, “they wanted to charge me a fortune for power,” he says.

Instead, Adamson installed his own diesel generators. “Then electricity got cheaper,” he says. The generators are still there, on standby, because power is unreliable in Vietnam.

Developing their products

In 2003-2004, Adamson finished developing his own specialty flow-back equipment, mainly valves and manifolds, to handle liquids involved in oil and gas production. He had also purchased a new product, a solar-powered pump. He began using the Vietnamese facility to produce parts for these products.

“We developed a good workforce there,” Adamson says. “It took several years. It’s tough to build a workforce from an agricultural society, because they aren’t used to clocking in to work every day. If you’re working a coffee field, you can go and work today or not—whenever you feel like it.”

Despite the money and employment Adamson provided, the government aggravation in Lam Dong Province continued. So, he and Mai leased 22 acres for 50 years in Binh Phuoc Province, which is closer to Ho Chi Minh City.

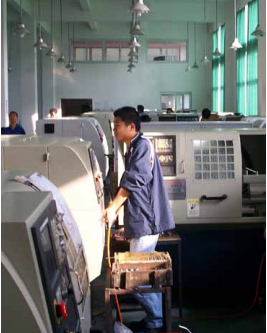

“My partner’s wife is an ex-Communist, and she got the land on the promise of jobs,” Adamson says. In 2005-2006, the company started building a one-million-square-foot facility in the new location. Upon completion, Adamson equipped it with more than 100 used CNC machines purchased from Japanese dealers in Vietnam. He also purchased forging hammers and presses stateside and transferred them to the Binh Phuoc facility.

Adamson uses the forging tools to make valve bodies and ancillary parts for the flow back product—the tech seals—for which his company is named. He also makes the tech seals in Houston, “but we focus more [in Houston] on the job shop business for local companies,” he says. There’s no forging in Houston.

Making money

Adamson doesn’t limit Vietnam operations to forging. “There is no sense in just forging there and shipping all that weight over here to finish,” he says. “I may as well take advantage of the labor. We forge the raw material, heat-treat it, and then machine it over there. We control the cost and quality for every step; it gives us a good cost advantage.”

“There are a lot of machinists that own businesses who run them like machine shops,” Adamson says. “I’m interested in running my company like a business. I want it to get me to where I want to be—to have my own product lines. I’m developing other product lines, like pumps. I want to delegate and get into other businesses.”

Adamson is also extremely loyal to his employees. “I’ve had three good months in a row [in Houston], and I’ve given out $25,000 in bonuses in each of those months,” he says. “My people are wonderful and work very hard. If you treat people well, you can be happy. That’s what matters.”

Competing globally

Founded in 1924, the niche for Detroit-based Central Screw Products was a “low-to-medium volume of non-standard parts,” says Matthew D. Heller, chief operating officer of the family-owned firm. “In the late 1990s, we started to get lots of pressure from customers about lower global pricing.”

After investigating India and China as possible manufacturing locations, the company chose China. “The big decision when you go international is whether you’ll contract, create a joint venture, or open your own facility,” Heller says. “We didn’t set up our own factory. Manufacturing parts is one level of difficulty, having a workforce is another. We didn’t want to get into human relations and politics.” So when Central Screw Products went to China in 2000, the decision had already been made to contract the work out.

Creating relationships

Central Screw Products worked with a consultant to locate potential companies in China who would be a good fit as partners. “In the beginning, there were language and cultural barriers,” Heller says. “It was good to have help.”

Language and cultural barriers are the two biggest for Americans who travel to Asia for business. “Asians are more reticent and are slow to establish relationships,” Business Strategies International’s James says. “They believe more in relationships than in signing paperwork. Americans tend to be awfully forthright, and that can be an impediment in dealing with Asians. They object to people who come on too strong.”

Asians won’t sign agreements until trust can be established. That takes a lot of groundwork before meeting a possible Chinese business partner. “You must find out a lot about them first so you’re not just asking them to tell you about themselves and so you can demonstrate your knowledge of them and their business,” James says.

In the early stages, consultants or others with expertise and contacts in a specific country can help. “It is very useful to approach contacts through formal channels,” James says. “Get a trustworthy source in the country who can introduce you to sources and contacts.”

And don’t expect to establish trust or build relationships long-distance. “Face-to-face is best, although much of the groundwork can and should be done beforehand,” James says.

Getting busy

Getting busy

Once Heller met the potential partners, “we worked with our customers and decided there were some flagship products they wanted to try out,” he says. Those products were pins and bushings. The orders were placed in mid- to late-2000, and the parts were delivered in 2002. “That’s set-up, making and proving samples, then making the parts and arranging shipping,” Heller says. After that, the company signed with several partners and began manufacturing products in China in 2002 and 2003.

“Doing business in China really requires a serious review of your business model and practices,” Heller says. “One of the pressures in the U.S. is less lead time, but internationally, a four-week timeframe isn’t feasible. You need a commitment from your customer and your own business for this change.”

Central Screw Products (CPS) worked closely with its stateside customers, explaining that things worked differently in China in a lot of ways. “When we went international, some customers were willing to change their model so CSP could make products abroad, but others weren’t,” Heller says. “When customers are willing to change their model, it lets us show both our international and domestic capabilities. We give our customers options.”

Learning the ropes

How do things work differently in China? “It is not true that manufacturing in China is the same as here, just cheaper,” Heller says. “Things are made differently. In the U.S., we’ll use a CNC machine with bar stock. There, a part may start as a cast or forged product. You start with different material and process it on different types of machines. We’ve had to use our manufacturing and quality knowledge to make sure that even though a part is processed differently in China, it will still work for the customer.”

Heller explains that, for example, raw materials in China aren’t the same as they are in the U.S. “In the U.S., 12L14 steel is readily available and machines well,” he says. That’s not so in China, so Central Screw Products must determine if it’s the specific chemical properties of 12L14 that are needed—low-carbon steel with a lead additive—or if another low-carbon steel with no lead would suffice. “We have to find what works in China and bring it to the customer,” Heller says. “The workforce is entirely capable of making a part, but it’s not the same part if it’s a different process. That can either be a problem or a significant competitive advantage.”

In 2008, Central Screw Products added a new division, CSP Global Inc., to reflect its proven international capabilities. That was also the year the company invested and built its own technical center in Jining, a city in Shandong Province, roughly halfway between Beijing and Shanghai. However, no core people from CSP Global stayed permanently in China to run the technical center.

The goal of the technical center was to “let us do things faster, better and more efficiently,” Heller says. Unfortunately, with no CSP Global personnel there at all times to take ownership of the center and its relationships with the Chinese partners, “it became a scapegoat for quality and timing issues.” If there was a problem with a product, the technical center got the blame. “We shut it down in 2009,” Heller says.

CSP Global also tried using third-party quality inspectors to check part shipments before they left China and assure that they met specifications. That experiment didn’t work out quite as planned, either. Parts arrived that didn’t meet expectations, and the Chinese factories blamed the third-party inspectors. That experiment was canceled, too.

“The difficulty we’ve run into again and again is the lack of ownership outside of CSP,” Heller says. “Consultants, third-party inspectors…at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter to anyone else if our customer gets its parts. The overriding theme of our nine years in China is that it’s not easy, you must be persistent, and you must own what you do 100 percent in terms of accountability. You must own your processes from start to finish.”

After nine years in China, CSP Global is sold on its partnerships and the benefits of manufacturing abroad. “It allows us to bring a new set of skills to customers,” Heller says. “It lets us find and utilize the strengths of our business. It’s given us a lot more opportunity in areas we wouldn’t have had before—parts we couldn’t have produced on our own floor, like rubber and plastic, and parts that were best to make in Asia for competitive reasons. Now we’re able to get that business.”

Sources for help in setting up business abroad

China Council for Promotion of International Trade: www.english.ccpit.org

U.S. International Trade Administration: www.trade.gov

Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry: www.english.korcham.net/

Hong Kong Government and Trade Offices in the U.S.: www.hketousa.gov.hk/usa/index.htm

U.S. Small Business Administration, International Trade: www.sba.gov/aboutsba/sbaprograms/internationaltrade/index.html

U.S. China Chamber of Commerce: www.usccc.org

U.S. embassies in the foreign country of interest

Foreign embassies and consulates in the U.S.

U.S. business/commerce organizations in the country of interest

Shipping machine tools abroad from the U.S.

Any citizen of the United States can start a business in an-other country (as long as it’s legal in that country) without stateside government involvement. If you want to transfer goods abroad from the United States, though, for export or to set up a shop, you must abide by the federal Export Administration Regulations and Commerce Country Charts. Both documents are created and maintained by the Bureau of Industry and Security in the Commerce Department.

The EARs specify what equipment or other goods can or cannot be transferred and if you need a license (export licenses are free). Machine tools are on the list. The other crucial factor is where you plan to ship the goods. That’s where the Commerce Country Charts come in. Find both of these documents and other kinds of help, both online and by phone, via the Bureau of Industry and Security’s Website, www.bis.doc.gov.

Today’s Machining World Archives September 2010 Volume 06 Issue 07