Usually I live my business life talking to people who are extremely skilled at cutting bars of metal into a lot of useful widgets and selling them for a modest profit to a company that assembles them into useful industrial products.

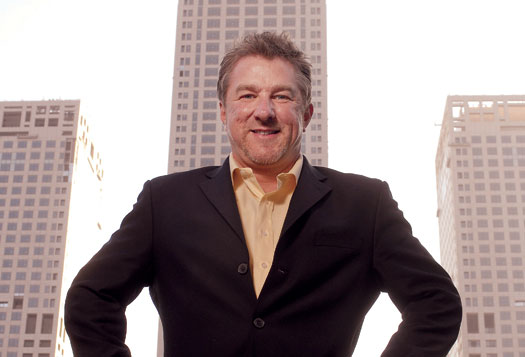

But a few days ago I had a lengthy chat with Mitch Free, who is playing the game somewhat differently than most of the folks in the machining business.

Mitch Free’s name is appropriate because he has freed himself from the conventional wisdom of the business, even though he happily runs a nice assortment of CNC lathes and mills at ZYCI, his shop in Atlanta. Mitch is a born and bred machinist, but he doesn’t think like one. He has wholeheartedly embraced 3D printing of both plastic and metal, but he acknowledges its limitations in accuracy. In metal, 3D printing produces a part of similar quality to a casting, but without the metallurgical integrity to withstand the high stress of many aerospace applications. But for a fuel nozzle like the one General Electric makes for the aviation market, it’s quite appropriate.

To Mitch, the beauty of additive manufacturing is that it is an almost perfect fit for the digital, cloud based world that views inventory as intellectual property, not plastic or metal pieces. He has launched a growing partnership with UPS, also based in Atlanta, to strategically attack the traditional imperative of stocking stuff.

Mr. Free has a lot of experience in the digital world, having started an internet based quoting clearinghouse called MFG.com during the dot-com boom. His work with MFG.com helped him grasp the link between the digital world and the manufacturing world.

A few years ago he wangled an invitation to UPS headquarters through a social acquaintance, only to be ushered into the inner sanctum of top management because the shipping behemoth happened to be looking for somebody like him who saw the strategic implications of no inventory, inventory management, and had the knowhow to make it happen.

UPS has a five million square foot logistics center in Louisville, Kentucky. Besides being a gigantic hub, it is also where UPS stocks inventory for a multitude of clients waiting for orders. What Free, UPS, and its clients understood was that physically stocking millions of pieces of stuff is expensive. They asked themselves, what if rather than stashing it in bins, you just had the digital data in the Cloud which you accessed on demand and then made the widgets within 24 or 48 hours in Louisville, then shipped them from there?

This was the concept that Mitch Free and UPS envisioned at the meeting in Atlanta, and they have made it happen in their old Kentucky home. Free says that he has 100 machines in Louisville, mostly 3D printers making stuff virtually overnight with the orders coming online via the Cloud.

Mitch believes UPS lives in fear of their biggest competitor and customer, Amazon, gradually replacing them as a primary shipper. Mitch says it is extremely likely that Amazon is also experimenting in this arena as they focus on every form of delivery vehicle from drones to Uber. The more links they take out of the supply chain, the closer they come to owning it.

Mitch Free knows Jeff Bezos, the head of Amazon, because one of Bezos’s companies, Blue Origin (his space transport company) did business with his MFG.com firm and partnered with him in 2007.

As I sit here enduring the ups and downs of the high production piece part world, companies like Mitch Free’s, Amazon, and UPS are looking past the sclerotic traditional inventory-dominated world. Free acknowledged that 48-hour delivery for most things is still just a dream, but it is a dream that a lot of money is chasing. As 3D printing improves it will challenge subtractive machining, but will also work in tandem. On small quantity production additive manufacturing will take a bigger and bigger share. The metal or plastic will make the rough part and the CNC millturns will finish it. Companies will pay a significant premium for speed. For UPS and Amazon that make the spread for inventorying and shipping, it means huge money. For Mitch Free and others who can adapt to the 24 or 48 hour inventory world it could be the gold ring.

In a few years we will see robots fill the aisles in Louisville and other distribution hubs. More products will be designed from inception for digitization and there will be a huge business in digitizing old semi obsolete parts that do not lend themselves to physical inventory because their yearly usage is so low. Think of all the old Air Force planes or tanks that need low volume replacement parts.

This is going to be a huge opportunity for folks in the machining world. If it costs the same to make one part as 25, and companies are going to buy one piece at a time, it will change the economics of manufacturing. That future is already working in Louisville.

Question: How are you adapting to an inventory light world?