Interview by: Noah Graff

Today’s Machining World Archive: May 2010 Vol. 6, Issue 04

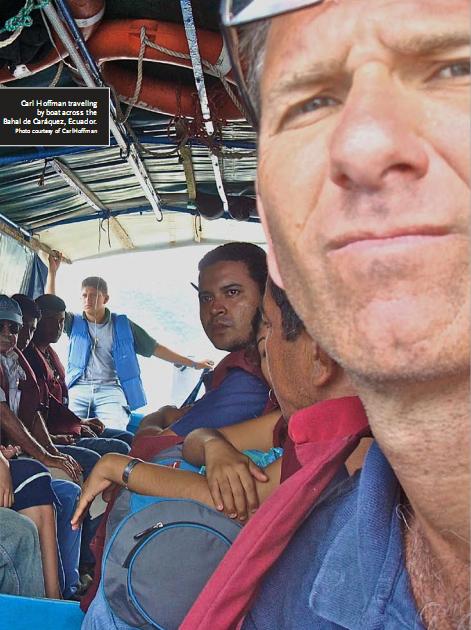

Carl Hoffman’s new book, The Lunatic Express, chronicles his travels throughout Asia, Africa, South America and the U.S., where he attempted to travel by modes of transportation commonly used by the natives, which were notorious for discomfort, tardiness and poor safety.

How did you get the idea for the book?

CH: I’d been traveling a lot for work over the last decade in places like the Congo, Sudan and South America. I saw minivans and trains just packed with people, and people riding on the roofs of trains. My journalist sensibility was asking me, “who are these people, where are they going and why are they moving around?”

How did these people look at you, as they were traveling out of necessity for work and you were this American traveling alone to document an adventure?

CH: They looked at me with incredible curiosity and openness. Most of these people don’t travel alone. They travel with family members. Most people spend very little time in their whole lives alone. They sleep in big piles in a one-room apartment or a shack somewhere, and then they have this incredibly long commute in a crowded minivan or matatu or train, and they have a job that’s full of people. They kept asking me, “Are you alone? Why are you alone? Where’s your family? Why are you here? Why aren’t you traveling in first class, or why aren’t you flying?”

Tell me about some of the ways you traveled. Which ones were the most dangerous?

CH: The Cuban airline, Cubana, statistically has one of the worst safety records. The plane from Toronto to Havana was a marquee fight, so it was a brand new shiny airplane and the stewardesses were all beautiful. But the fight from Havana to Bogota was a different beast. It was an old Russian Ilyushin, and the seat backs didn’t work, people were smoking and stuff was flying out of the overhead bins. I also traveled on busses, auto rickshaws, bicycle rickshaws and ferries, which are ubiquitous in certain places like Bangladesh and Indonesia.

They get incredibly packed with people and they have no life vests and often no lifeboats.

When did you feel most in danger?

CH: The scariest thing probably was when our bus broke down in Afghanistan in the middle of nowhere. Everybody got off to stretch their legs and I got up too. As I was going to go outside an Afghan guy I was traveling with said, “No, don’t get out. This is a really bad area.” That was when I realized that I was really treading a narrow line. Of course, 10 minutes later they got the bus going and off we went.

At the end of your journey you took a Greyhound bus from Los Angeles to D.C. How did that experience compare to the rest of your travels?

CH: In some ways that was the worst leg of my trip, not because the Greyhound buses were particularly dirty, they weren’t, or late, they were wealthily on time. America just looked like a very grim place. The luggage of choice for Greyhound passengers was a plastic garbage bag, quickly stuffed with a few clothing items. But when you’re on an India train or you’re on an Indonesia ferry in steerage, they’re eating such good food and they’re praying and they’re dancing. But I think one has to be careful about over romanticizing the lives of the Third World. They’re not lonely, but they live very difficult lives

Did you see much manufacturing going on during your travels?

CH: Well, one really cool thing throughout the Third World is the amount of small scale manufacturing and small scale human enterprise. In Bangladesh, you can walk down the street and there’s nothing but bicycle rickshaw shops, and guys are welding and banging and doing it in bare feet without shirts. It’s hot, and they’re building things. I had a bicycle messenger bag and its zipper was broken. One day I was just sitting around having tea in the park with some shoe shiners and an ear cleaner that had I buddied up with. One of them suddenly pointed at my zipper and he grabbed my bag and went at it with a little wax from his kit and a razor blade. And with incredible care, he fixed my zipper. It’s the sort of thing that only a poor Indian in a park would do. We don’t fix a zipper. We take it in and send it away, and maybe they send back a new one or they rip the whole zipper out and sew a new one in. This guy fixed it. They have a whole mentality and culture of fixing things and building things, and it’s kind of been lost here.

Find out more about Carl Hoffman’s new book and travels at www.lunaticexpress.com.

1 Comment

I like the comment about the lost art of fixing and building things…. I thank my father for making sure that didn’t get lost in our family. I like fixing things if they are broken, partly to see how they work but also to keep my “manufacturing” state of mind working. Sure it might be less expensive to replace certain things outright or send them away to get repaired, but that’s not the point. A lot of people forget that….. Even if you are not soley self-sufficent it is still good to know.