Today’s Machining World Archives March 2011 Volume 07 Issue 02

By Barbara Donohue

Creep feed grinding, a high stock removal technology, uses abrasives to cut any material you can think of, precisely and nearly burr-free.

What is it used for?

Creep feed grinding, an underutilized and maybe unfamiliar technology, is ideal for heavy material removal. It cuts difficult-to-machine materials, easily holds precision tolerances, and leaves few, if any, burrs.

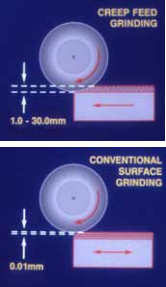

Creep feed grinding uses much deeper cuts and a decreased feed rate compared to conventional grinding. “Grinding is often thought of as a finishing operation. Creep feed grinding takes it to a whole new level by combining the higher stock removal operation with a finishing capability, all at once,” said Ken Kummer, CEO at Abrasive Form, Inc., Bloomingdale, Ill., a machine shop specializing in creep feed grinding.

What’s in a name?

So why, with all these advantages, isn’t everyone using it? The problem is its called creep feed grinding, said Stuart C. Salmon, Ph.D., president of Advanced Manufacturing Science & Technology, Rossford, Ohio, who has been called the father of creep feed grinding. “You’ve got creep in there, and worst of all, grinding, because everybody hates grinding.”

People who could use it won’t even read an article with grinding in the title, Salmon said. They will think, “Well, here’s a process that takes forever to remove hardly any material.” And creep feed sounds like it should be even slower. “Everybody thinks it has to do with grinding, but it’s really a high stock removal process,” he said. It’s milling, but with an abrasive tool.

Creep feed grinding was developed more than 50 years ago in Germany and has made inroads in Europe and in some shops in North America. But now the technology may be coming into its own. “Aerospace super-alloys give people fits. You can’t use conventional tooling on those. Then we start moving into the area of ceramics and cermet-type materials,” said Salmon. “Even something that sounds like it should be easy—whisker-reinforced polymer. If you try to fly cut or mill it, the plastic machines easily, but the fibers get torn out by the big cutter. With grinding, you get an absolutely smooth finish.”

No matter what you call it, this technology deserves attention. “I have not come across a material I cannot creep feed grind,” said Salmon, and as a longtime consultant in abrasive machining technology he’s seen a lot of materials. “One of the latest ones has been cermet materials for racing cars—titanium aluminide. It work-hardens if you try to machine it with big-chip machines, but you can grind it very easily.”

Big chip, little chip

“What’s happening with creep feed grinding is much like a milling process, but using a grinding wheel instead of a milling cutter,” Salmon said. It’s just making a lot more, smaller chips. “We’re taking a depth of cut similar to that with which you would use a milling cutter and plowing through material at milling-type speeds. And you say, ‘Well, so what? What’s the big deal there?’”

“A fine example is with a hand gun manufacturer. When the Brady [handgun] bill [passed] manufacturers couldn’t make guns fast enough. They had to look at how they could increase production,” Salmon said. One manufacturer looked at improving the process for milling the forms on each side of the barrel.

They considered creep feed grinding, but for the actual machining process, it was a wash. No savings. However, “milling left you with a gnarly looking surface and a big burr on the end of the part,” Salmon said, “Whereas the grinding process gave you a very smooth finish and virtually no burrs, which meant the hand benching and polishing of the gun barrels was minimal and the saving was huge.”

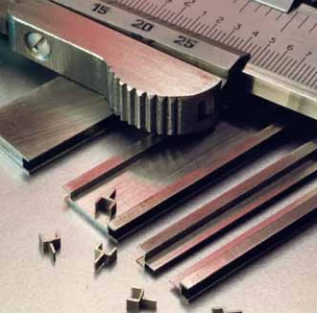

The process is economical in many ways. “Forms are normally ground from the solid with no pre-milling or forming required,” Kummer said. “If a part requires heat treating, grinding from the solid after it is hardened eliminates an operation and circumvents the distortion problems associated with the old ‘pre-mill then grind’ process. Furthermore, the process is close to burr free, and burrs can be an expensive problem.”

Unintentional discoveries

Edmund and Gerhard Lang first performed creep feed grinding back in the 1950s in Germany, quite by accident, Salmon said. They were experimenting with an electrolytic grinding process and “one day, so the story goes,” he said, “they forgot to turn the current on. The grinding wheel walked through the workpiece with no electrochemical anything.” Creep feed grinding was born from that experiment.

In the 1970s, Salmon was working at Rolls Royce and made his own surprising discovery. “Then I came along,” he said, “not trying to find any particular process. I was doing some analysis of why creep feed works the way it does. I decided if I could maintain the grinding wheel’s sharpness, I could analyze a little more of what’s going on.” So I continually dressed the grinding wheel as I was grinding with it, and all of a sudden my specimen material, which was supposed to be unmachinable, was machining like butter—there was never a burn or a burr on it,” he said.

“I just kept increasing the feed rate and [went from] feeds of millimeters per minute up to meters per minute. That’s how the continuous dress creep feed process came up,” Salmon said.

Wheels

“Traditional creep feed grinding demands a high-porosity grinding wheel. It looks very open, and you could almost pick the grains out of it with your finger. It has the delicate skeletal structure of a grinding wheel, because it needs lots of room for the swarf. The uninitiated [might say], ‘This wheel—it seems as if I just sneeze at it, it falls apart—how can it machine material as fast as a milling cutter?’ In the creep feed process, I’m spreading [the force] over a very large area—it’s actually much lower, if you look at [pressure], than it typically is for a conventional grinding wheel [high force over a small area].” Aluminum oxide and silicon carbide are the usual abrasives.

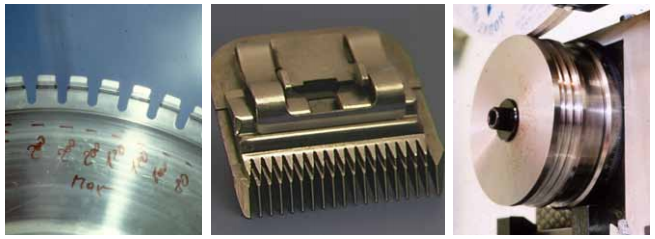

Wheels using superabrasives—cubic boron nitride (CBN) and diamond—made possible a new type of creep feed grinding: high efficiency deep grinding (HEDG). These wheels made of metal have a single layer of the superabrasive on the surface. Run at extremely high speeds, the HEDG process rapidly removes material in fine, dust-like particles, so you don’t need the porous wheel, and it doesn’t require wheel dressing.

Do not try this at home

Some who hear about creep feed grinding will try it on their own conventional grinding machines by taking a heavy cut, Salmon said. But this provides disappointing results, and then they may reject the creep feed concept. Creep feed grinding requires the proper combination of the right machine (rigid and high-powered), wheel (extremely porous, designed for the job), coolant delivery (high pressure and in the right place) and other factors. People in the business will tell you that any one factor can ruin the process’s efficiency.

Grinding tolerances at milling speed

“Anything that is a form-milled process if you think of it, is so easy because grinding machines hold to less than a thousandth. You say, ‘Oh, easy. Plus or minus half a thousandth, that wouldn’t be too difficult, either,’” said Salmon. “But if you said those sorts of tolerances to a milling person, it would be, ‘Oh my goodness—I need to make a way around that.’”

Applications

A common type of application is “putting slots into a pump rotor for a vane pump,” Salmon said. “To put in the slot accurately, straight, with no burrs, is difficult to do with a milling cutter, but with a grinding wheel you can just plunge it in, and go on to the next one.”

PGM Corp. uses creep feed grinding for parts used in many different industries, including firearms, copiers, pumps, and actuators, said Todd Hockenberger, corporate vice president, at PGM Corp., Rochester N.Y., a shop that offers creep feed grinding. His company uses the process for surgical and other blades, giving a nice, sharp edge. Using creep feed grinding to make the blades for a bagel cutter allowed them to produce the serrations and the edge in one shot, he said.

Abrasive Form specializes in blades for turbines, for both aerospace and power generation, Kummer said. The company’s 50 creep feed grinders also crank out parts for other markets, including medical, dental, automotive, pulp and paper, heavy machinery and hand tools.

A problem-solving technology

“It is exciting when people see the process. It’s quite an eye-opener, especially if they have some difficult-to-machine material—here’s this monumental problem they have and all of a sudden this wheel walks right through it,” Salmon said. “And relief comes over their face. It’s really quite something.”

“I would say that if you mill or turn or broach, maybe you should consider creep feed grinding,” Salmon said. You can check out the technology by contracting work to a shop that specializes in the process.