Sure, any old vise can hold the part on a machine table, but a well-thought-out workholding scheme can help you squeeze more chip-making time out of every shift.

Certain basic principles apply to workholding, whether you’re using your father’s 6-inch manual Bridgeport vise or an intricate hydraulic fixture. Dr. Edward De Meter, professor of industrial and manufacturing engineering at Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pa., does research on workholding. He outlined the basic functions of any workholding method as follows:

- Repeatably locate the workpiece with respect to your data reference frame.

- Restrain rigid-body motion of the workpiece—hold it down so it doesn’t fly off the table.

- Impart overall structural rigidity—prevent the fixture and workpiece from being a source of chatter.

- Hold the workpiece without excessively distorting it.

- Accommodate dimensional variability in the raw workpiece —often an issue with castings, forgings or weldments.

Many types of workholding devices, from simple collets and vises to complex fixtures, will perform these basic functions. But “workholding is not just holding the part,” said Wendy Kuch, product manager at Chick Workholding Solutions, Warrendale, Pa. “It’s a significant part of efficiency [in your machining operation].”

The workholding method is part of your whole machining system: the machine, the tool, the program, the operator and the workholding. All the parts have to function together in an effective way if you’re going to make the most profit from your machines. The key is maximizing the work you’re being paid for: removing material—making chips. To do this, you optimize the tooling, feeds and speeds. You’ll also want to minimize the amount of time the spindle is idle. That’s where your workholding choices can pack a big punch.

In the new workholding scheme, three Chick Pneu-Dex four-sided indexers were mounted on the machine table. Two workpieces were clamped in vises on each face of the Pneu-Dex units. These vises allowed machining of three surfaces of a clamped part.

The result was 24 workpieces on the table, three surfaces machined in each cycle and five times as much throughput on the machine. The time savings came from handling (two clamping processes instead of six) and “amortizing” any machining cycle overhead, such as the tool change time, over the 24 workpieces.

Workholding tailored to your needs

A wide variety of specialized workholding devices is available. You may find that a whole new approach to workholding—such as a vacuum table—would serve you well, or maybe a new type of collet or vise could meet your needs.

To hold thin-walled or delicate parts during turning, you can use a force-limiting chuck. The FL force limiting step chuck from Hardinge, for example, uses springs to limit the clamping force without having to manually adjust the drawbar force.

FlexC vulcanized collet heads, also from Hardinge, fit into an adapter and provide fast changeover using a special wrench. They have a wide gripping range to allow for stock variation. The rubber that fills the space between the segments of the collet helps keep chips and sludge out of the spindle area.

A vise with quick-release jaws that slide forward and back allow fast load/unload. The One-Lok single station CNC vise from Chick also offers a quick-change jaw system, which allows jaw changes with the turn of a single locking screw.

Besides collets, vises and other workholding devices, a lot of different accessories are available that can finetune your workholding to do exactly the job you need it to do.

For a better grip without having to apply a lot of force, you can use special rippers available from Fixtureworks, said Justin Gordon, general manager at the Fraser, Mich., company. To protect a polished surface or hold a delicate part, you can use grippers with a textured urethane surface. Grippers with a high coefficient of friction offer the hold you need with lower force. Fixtureworks also offers grippers coated with an abrasive diamond layer, which provides high friction for secure holding with relatively low clamping forces.

Some vise designs feature quickchange jaws, which help speed setup when changing over to a new job.

The Hydramax hydraulic piston vise jaw system available from Kurt Manufacturing Company, Minneapolis, Minn., provides one jaw with four to 12 hydraulically-linked pistons, which automatically and independently adjust when you close the vise, said Steve Kane, sales and marketing manager for the industrial products and engineered systems group. This allows you to hold multiple parts in a single vise, or to clamp castings or irregularly shaped parts. The opposite jaw is machinable aluminum, enabling you to provide pockets for locating the other end of the workpiece or pieces.

Finding savings

Looking at your process with fresh eyes can help you see opportunities to streamline machining a particular part. “One of the greatest tools is video,” said Chick’s. Set up a video camera where it can see the machining area. Run the program without a workpiece in place and record the whole cycle, including the part loading and unloading processes. Then, watch to see when the tool is cutting and when it’s not. You may be surprised at what you see.

Your machining center may feature one-second tool changes, but the total chip-to-chip time for swapping a tool out of and into the spindle may be many times longer. Chick’s Swann said he had seen chip-to-chip times of up to 11 seconds for tool changes. When you view the video, pay special attention to all that happens during a tool change.

An unexpected discovery from watching videotaped time studies, Swann said, was that it took four times as long to blow the chips off a setup than to clamp and unclamp the part. His company and others offer vise products with a fully sealed base to keep the chips out.

Making the most of your workholding

Many shops use whatever workholding device they happen to have or whatever comes with a machine, said Sue Draht, marketing/customer service manager for workholding at Hardinge Inc., Elmira, N.Y. “They make the application fit the workholding, instead of making the workholding fit the application.”

Giving some thought to your workholding method can make a big difference in your profitability. You may end up using some of the many standard workholding products available, modified versions of them or even custom fixturing.

People often forget to take into account their workholding needs when they purchase a new machine, Kurt’s Kane said.

The workholding could be a complete package supplied with the new machine, said Rick Schonher, product manager for workholding at Hardinge Inc. If purchased at the same time, it can be included in the financing. With the FlexC collet program, he said, he has recently found customers requesting a quote when they’re purchasing a machine.

If you encounter a challenging application or suspect that an existing process could be improved, it can pay off to consult with workholding suppliers to see if a new or existing product could do the job. “If we can get in on the initial [production planning],” said Draht, “we can sometimes offer solutions they didn’t think about because they didn’t know products were available.”

Though fixtures and vises and chucks and collets may seem like passive participants in the machining process, they can help you get more production out of your machines and make a big difference in your bottom line.

*************************************************************

Light Activated Adhesive Gripping

A new technology for fixturing complex workpieces

At the Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering, Pennsylvania State University in University Park, Pa., Prof. Edward De Meter has developed a new workholding technology designed to solve fixturing problems with complex and/or delicate parts. Light Activated Adhesive Gripping (LAAG) is a conceptually simple approach, using adhesive to hold a workpiece to a fixture.

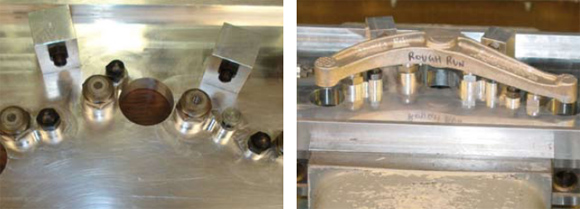

The LAAG process works like this: provide a fixture composed of a base plate and standoffs that locate the workpiece at as many points as needed. In strategic locations, provide flat-topped grippers that clear the workpiece by about 0.003”. Each gripper has a ceramic core that can transmit ultraviolet (UV) light. Place some UV-curable adhesive on the tops of the grippers and set the workpiece into place. Shine intense ultraviolet light through the center of the grippers to cure the adhesive, and the part is fixed to the base plate,

ready to machine.

After machining, release the workpiece from the grippers by simply lifting up on it with a tool, or twist the grippers to break loose the adhesive. Use hot water or other means to clean any adhesive residue from the grippers and the workpiece. Then you’re ready to do it again.

Though the adhesive provides 6000 psi of grip, no clamping forces are applied to the part, so LAAG holds the workpiece in its free state, without any deformation. For delicate parts, the twist-off release method can be used, which subjects the part to very little stress.

No vise or other fixture covers any part of the sides of the workpiece, so LAAG allows access to the top and all sides of the part. If you need access to the bottom of the part, you can use a fixture plate with a cutout/picture-frame configuration.

LAAG is ideal for complex, low volume parts for which you don’t have specialized fixturing. Parts that are extremely complex to hold,

impossible parts you can’t hold mechanically, parts that start out as castings, or forgings where the geometry may vary. In a conventional workholding setup, if you can hold them at all, complex parts may require an operator to spend 15-25 minutes setting up

clamps and adjustable supports, De Meter said.

Master Workholding, Inc., Morganton, N.C., offers a commercial version of the LAAG system. The basic equipment to get started with LAAG—a setup station, special UV lamp, etc.—costs $20,000 to $25,000, according to Keith Cline, engineering manager at the company. Once you have the setup in house and learn to use the LAAG process, however, you can put together a fixture for $6,000 or

$7,000, he said, where a hydraulic fixture to hold a complex part can run $30,000.

“We’ve had customers come in and say, ‘There is no way we can machine this in one setup—we’re using seven or eight setups,’” Cline said. Using a picture-frame fixture plate on a trunnion to allow access to the bottom of the part, some of these customers have indeed been able to machine the whole part in one setup, he said.