Today’s Machining World Archive: June 2007, Vol. 3, Issue

Coil springs, flat springs and wireforms perform varied functions in many types of mechanical assemblies

Springs are “flexible members that store energy,” according to the Handbook of Spring Design published by the Spring Manufacturers Institute, Oak Brook, Ill. Other definitions of springs highlight their ability to return to their original shape after being compressed, extended or otherwise distorted; one definition describes this quality by saying a spring is a device that has “memory.”

Whatever the size, shape or material of a spring, its useful characteristics are its capacity for storing energy and its ability to provide force by purely mechanical means in a limited space. Springs can take on potentially damaging mechanical energy, act as fasteners, or provide power to do useful work.

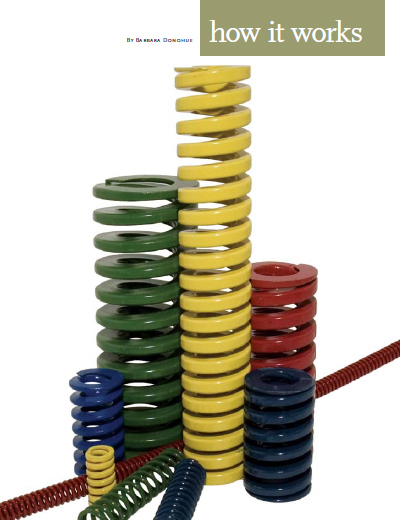

Familiar coil springs, made from wire or bar, work in compression or extension, or in the case of torsion springs, in rotation. Wire can also be shaped into “wireforms,” which often function as clips or torsion bars. Flat springs are made from strip stock bent into shape. Spring materials range from high-carbon steels to copper alloys to titanium to high-temperature alloys, depending on the application.

Here are several kinds of springs you may encounter. Other types and materials are available.

Coil springs

Push, pull or rotate. The most familiar springs are those made from coiling wire or bar into a helical shape.

Compression springs are wound with spaces between adjacent turns, so the coils can move closer together with increasing compressive force.

One application of compression springs is deployment of ram air turbines in aircraft. This turbine generates electricity when the plane loses power; the pilot presses a button and the turbine pops out from the belly of the plane, said John King, manager of engineering and sales at Atlantic Spring Division, MW Industries, Ringoes, N.J. The springs that do this are made from titanium bar one inch in diameter; the springs are about one foot high and eight inches in diameter, he said.

For another aircraft application, Spring Manufacturing Corporation, Tewksbury, Mass., makes tiny compression springs wound from 0.010-inch Inconel wire. Hundreds of these small springs maintain a seal inside jet engines, said company president Roger Desmarais.

Compression springs specially designed for use in die sets are available off the shelf. The springs are designed to fit in a hole and over a shaft, and are usually color coded to indicate strength. They are usually made of rectangular wire, which maximizes the amount of material in a given space, reducing the stresses in the spring, said Mike Kime, manager of product engineering/quality assurance at Matthew-Warren Spring Division, MW Industries, Inc. Logansport, Ind.

Extension springs are designed to be pulled on, and generally are wound with no space between the coils. They may be wound with or without an “initial tension,” which requires the pull on them to be above a certain level before the spring will extend. You can find extension springs in such applications as overhead garage doors, spring scales, and screen-door springs.

Torsion springs store rotational energy and provide torque. A torsion spring is usually wound with a small space between turns to prevent the friction that could occur if the coils touch each other.

Familiar applications include mouse traps, spring-type clothespins and the clips on clipboards. Torsion springs can do heavy lifting, too. On the Trident submarine the hatch covers are five feet in diameter and two feet thick, King said. Yet one sailor can open the hatch unassisted. The springs? Beryllium copper torsion springs made from one-and-an-eighth-inch-square stock.

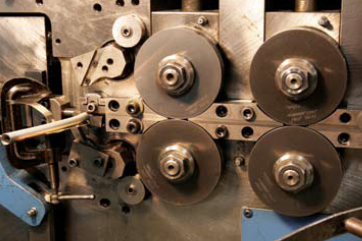

How they’re made

Coil springs may be wound from most any diameter wire, but commonly spring manufacturers will work with wire in a range of, say, a few thousandths to within a fraction of an inch. After winding, most coil springs are treated to relieve the residual stresses from winding. For example, stainless steel might be heated to 500 degrees F for an hour, said Desmarais.

Larger wire is hot-wound. Kime said his company winds up to two-inch-diameter wire, and anything over five-eighths is hot wound.

Some of the largest springs ever made, King said, were the compression springs used in construction of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) installation at Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado, which opened in 1966. To help protect the facility from a nearby nuclear blast, it is supported on springs wound from four-inch diameter bar, four or five feet high and over two feet in diameter, King said. At the time the facility was built, there was no equipment available to wind springs that large, King said, so special machinery had to be developed to make the springs.

Flat springs

Any part made from thin stock and used to provide energy storage or force can be considered a flat spring. Often they are stamped or made on four-slide machines (see “For more information” sidebar) to make complex shapes for such applications as clips and electrical contacts.

Spring washers make up a special class of flat springs. Spring washers are installed around a bolt, rod or shaft. hey can provide force to create a preload or prevent threaded fasteners from loosening, for example. These include familiar split-ring washers, wave washers and slotted-washer designs, as well as Belleville washers.

Belleville washers, look a lot like plain washers, but they have a cone shape, so they deflect slightly as a load is applied. They provide a great deal of energy storage or force in a very compact package. They are used where very high load and very low deflection are required, such s providing high bearing preloads on large truck or agricultural transmissions, or in clutch applications, said Kime. When stacked up in various orientations, Belleville washers can economically provide even higher loads in relatively small spaces.

Often manufactured from high-carbon steel, most Belleville washers are made in stamping presses. Very large ones need to be machined, Kime said, such as the Belleville washer eighteen inches in diameter, with an eight-inch ID.

Winding up

Power springs, also known as clock springs, are an effective use of space, providing a lot of torque in a small area, King said. Now that most clocks don’t have springs, these are perhaps most familiar as the key-wound power for wind-up toys. They have a spiral shaped flat spring retained inside a housing. These springs are sometimes used in specialized applications such as farm equipment and large valves, King said.

Constant-force springs

With most springs, the force goes up as the deflection increases. But consider your retractable steel tape measure. You pull it out of its housing, and it pulls itself back in. It may be 25 feet long, but it’s about as easy to pull out the twenty-fifth foot as it was the first. This is an example of a constant-force spring, said King.

All kinds of retraction and counterbalance applications use constant-force springs. For example, a constant-force spring retracts the fabric tape barriers that keep you in line at the bank. Today’s double-hung windows use constant-force springs to counterbalance the sashes, instead of the old system of weights, ropes and pulleys.

How are constant force springs made? King said the process was invented in the 1930s, and is similar to curling the ribbon on a gift package. High-strength stainless steel strip is run over a sharp edge, and it curls up into a cylinder.

Other springs

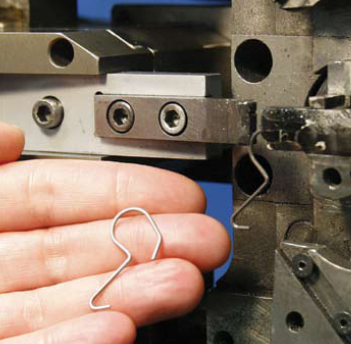

Wire shaped to a functional form can serve as a clip. Familiar wire forms are hairpin or horseshoe clips, paint can hooks, and paper clips.

Often thought of as fasteners, snap rings or retaining rings, are actually springs. They are commonplace in mechanical applications such as vehicle transmissions. However, they also turn up in some surprising places – implantable medical devices, for example. Spring Manufacturing Corporation makes a slender titanium ring about an inch and a half in diameter that retains a plastic insert in a hip joint replacement.

The force be with you

Most types of springs provide a force that increases with increased deflection. You have to exert more force as you push or pull the spring farther. In their working range, basic compression and extension coil springs have a consistent, or linear, relationship between force and deflection. Pull or push it twice as far, and you have to exert twice as much force. With variable coil spacing or spring diameter, compression and extension springs can be designed with more complex force/deflection characteristics.

You measure the behavior of torsion springs as a force/angular deflection relationship, and flat springs each have their own complex force/deflection relationship. Constant-force springs, as mentioned above, provide a consistent force over very long deflection.

Design

The spring is often the last part of the design a customer will look at, said Desmarais. The designer wants a certain load in a certain space, and sometimes this load is more than can be accommodated in the desired space.

The design of a simple spring includes the material, wire diameter, spring diameter, number of coils, pitch between coils, treatment of the ends, as well as the desired working load, space available, temperature, type of loading, etc. Your spring manufacturer can check the spring design to make sure the spring will operate in a stress range well below the material’s ultimate tensile strength, and can withstand the operating conditions.

Visit to a specialty spring manufacturer

On the shop floor at Spring Manufacturing Corporation in Tewksbury, Mass., you can carry on a conversation in a normal tone of voice. Here, metal parts are being fabricated, but there is no raucous sound of metal being cut, or thunder of stamping presses smashing metal into shape. A few spring-making machines quietly form wire into coils or clips, and long lines of benchtop pneumatic presses stand ready to bend metal, step by step, turning strip into flat springs, or wire into wireforms.

Company president Roger Desmarais started the business in 1979, and now, with about a dozen staff, produces custom springs for many applications in this 12,000-square-foot facility. Major markets for the company’s products include medical devices, aerospace, and semiconductor manufacturing.

His company specializes in custom springs, Desmarais said, but this doesn’t necessarily mean they have to be exotic or difficult to make.

“All springs are different and designed to work in a [particular] application,” Desmarais said. “The key is to never design a catalog spring into a product without having a specialty spring manufacturer look at it. Catalog springs can get expensive,” he said, as there usually isn’t very good pricing on high quantities.

Desmarais told about one medical device company that had, over time, bought 50,000 small springs with ground ends from a catalog before they called him when their catalog supplier was out of stock. He quoted the spring, but also looked at the application and noticed it didn’t really need the expensive secondary grinding process. So, besides receiving volume pricing, the customer could do without the ground ends. “We saved them a lot of money,” Desmarais said.

Different kinds of springs turn up just about everywhere. “There’s hardly anything manufactured that doesn’t have a spring in it,” said Kime. If you have need of springs for a project or assembly job, especially in volume, or to unique specifications, talk to a specialty spring manufacturer early in your design process.