Danny Books stands looking like the live version of a some toy soldier from the 19th Century, ready to bayonet the unworthy standing before him. He presses his implement forward and the lathe wheel in front of him whirrs and shudders. The metal on the lathe splays outward into and out of a bigger bell-like shape, the implement pressing tightly at its middle so he gets it just right.

Breathing deeply and adjusting his protective glasses, Books stands back a bit and shuts down the lathe. A closer look at that bayonet-like implement shows that it looks like one of those old baseball bats from the 1950s, the ones your dad had in the garage and taped up for you for your first pee-wee league game. It was too big, too put back together, but it was from Dad, so you took it to the game.

Turns out, it is about the same for Books. “Well, yes, it is a baseball bat,” said Books, who is the chief guy making the bells for trombones, tubas and other large horns for the E.K. Blessing Company, one of the largest purveyors of student band instruments in the world. “I hollowed it out and filled it in with something stronger, and put foam padding on it wherever it fits into me. “High tech, huh?” said Books, with a trombone-like laugh. You almost expect Professor Harold Hill to come down Beardsley Street in front of the Blessing plant in this mid-sized Northern Indiana city, pumping his baton and leading the River City Boys Band. Just down the street, the Elkhart River does drain into the St. Joseph River at Island Park, and while Meredith Wilson didn’t set his show, The Music Man, in Elkhart, he could have.

For Elkhart has long been, and continues to be, the center of band instrument manufacturing – primarily student band instruments – not just in the United States, but in the world.

“It all started with C.G. Conn, who was quite the guy in 1875 around here,” said Vincent McBryde, who has worked for several of the Elkhart music businesses and now consults for Blessing, while also being one of the folk historians of the business.

“Conn was a cornet player and got into some altercation where some guy hit him in the mouth,” said McBryde. “That is, as you may imagine, not good for a cornet player. He developed a real sore, so he invented a mouthpiece with a cushion.”

McBryde said Conn’s cornet reputation soared, and whether it was because of the new cushioned mouthpiece, or just general practice, other cornet players weren’t going to take any chances.

“They all said, ‘Can you make me a cornet with that mouthpiece’,” said McBryde. “One thing led to another and he started making them here. Other manufacturers came here – the Selmers who made clarinets and Gemeinhardts who made flutes, and the Lintons who made oboes and bassoons.”

Randall A. Johnson is the president of Blessing, the company his great-grandfather E.K. started in 1906, trying to perfect valves in a cornet.

“We’ve made everything over the years, but we have mostly concentrated on brass instruments,” said Johnson. “Things have consolidated and broken up and gone every which way here over the years, but we still believe it is a good American business, and we like that many companies have chosen to stay here.”

It is not all completely cheery and “Music Man”-esque in Elkhart. Some of the manufacturing – or at least the assembly – has gone off-shore. The factories generally work one shift – more often than not 6-to-2 or 7-to-3, so everyone has family time or tavern time at the end of the work day.

But, still, while other manufacturing areas have become ghost towns, and solid mid-20th-Century places like Detroit and Cleveland and Harold Hill’s hometown of Gary, Indiana, are near-unrecoverable, Elkhart thrives on tradition and spunk – and sometimes what seems like impossibly homespun ingenuity.

Like Todd Hesselbart who stamps the brand names on the Blessing horns. This is no automated stamping machine. The trumpets and trombones and mellophones are too delicate and oddly-shaped to go through such a stamper, McBryde said. So Hesselbart invented a better way. He hooked up a 1950 Plymouth steering wheel to a roll-stamper, to have a big handle to grab onto while lining up the instruments.

“I eye it up and clamp it down,” said Hesselbart. “I go back and forth, back and forth, so every letter is just right. A lot of the work here is people who have done it for ages eyeing it up. It is not anonymous. It is a craft.”

Taped-up baseball bats? Ancient Plymouth steering wheels? What century is this place in?

“We are in the business of giving first-time people the best possible instrument we can,” said Mark Hutchins, vice president of marketing for Gemeinhardt, a 60-year old purveyor of brass and woodwinds, mostly flutes and piccolos, primarily for the student market, where Blessing and Conn-Selmer, the largest music business in Elkhart, also send the majority of their wares. “For a while, people thought that eBay or Wal-Mart were going to kill us with cheap $150 flutes, but it just hasn’t happened.”

Primarily, it hasn’t happened because of the way most people – primarily school kids – get their first, and even second or third, instruments in North America.

According to Dan Del Fiorentino, the historian for the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM), based in Carlsbad, CA, while Elkhart was a center for band instrument manufacturing for decades before World War II, it began to thrive even more soon after the war.

“First, even in the 1930s, the band instrument business was big,” he said. “It was the era of the big swing band, and every little town had its own band, not to mention all those that traveled. There were 900 traveling territorial bands in the swing era. They ended up coming to Elkhart lots of times for their instruments.”

After the war, said Del Fiorentino, various governments had to figure out what to do with veterans.

“They made a lot of them teachers, but they had to find subjects to teach. Music seemed like a good one,” he said. So governments supported music education and, like Harold Hill in the fictitious early part of the century, they needed instruments to give the potential students.

Perhaps the popularity of The Music Man when it hit Broadway in 1957 was because in the decade before – and decades to come – each set of parents to rent their kids instruments, just as they bought them in the play and movie, had gleams in their eyes that one day their kid would be the next Tommy Dorsey or Benny Goodman or Al Hirt. In any case, it gave a new life to places like Blessing and Conn-Selmer, which went heavily into the student instrument business.

Student instruments can be junior-sized pieces – like flutes with smaller keys, or trombones whose longer tubes do not stretch so far out. More often, though, they are more sturdy versions of delicate professional instruments using, for instance, silver plate or harder brass instead of a higher grade of silver or more malleable metals.

“The design differences are really small, though,” said Hutchins of Gemeinhardt. “A student flute that sells for $400 has 300 moving parts, the same as the professional’s $30,000 instrument. What is important, though, is that first instrument has to sound good, or else there will never be a step-up instrument and, in the end, a professional instrument. If you do too much mass production, that won’t happen.”

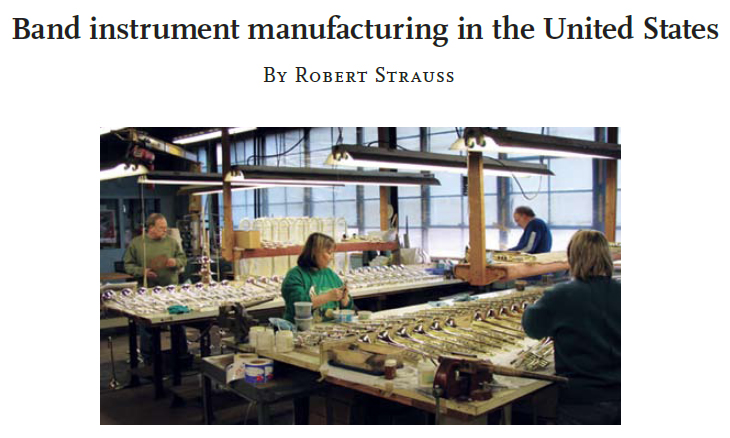

At the Blessing plant, as many as 60 workers could have some hand in making what seems like a simple trumpet or trombone. While not everyone uses that taped-up baseball bat or the Plymouth steering wheel, they are not using sophisticated machinery for the most part.

Curtis Perry, for instance, has, for the last nine years, worked primarily as the person who makes sure the valves on Blessing trumpets line up correctly. He takes three valve casings and wires them together, often just using a simple jig to do so.

“After a while, you can just see how to wire them,” he said. “You have a case for a set number and they all get their acid bath to clean them up. I can do 200 of these a day without a problem. Then it goes on to the next person.”

There are a lot of soldering guns and assembly stations and a seemingly incredible amount of people who “eye up” things. Amazingly, the levers for the spit holes in the trumpets and trombones are bent to the correct angle by people putting them in vises and turning them just so.

There are a lot of soldering guns and assembly stations and a seemingly incredible amount of people who “eye up” things. Amazingly, the levers for the spit holes in the trumpets and trombones are bent to the correct angle by people putting them in vises and turning them just so.

“These are just people who know what they are doing,” said McBryde, going from work station to work station as if the factory tour were a trip through a Disney ride. “They are the people of Elkhart and this seems to be what we are good at here.”

They are also good at – and this is hardly surprising – playing the instruments they produce. The marching bands at the three high schools in the city routinely win state and national competitions.

“We have an active municipal band, which is a great amenity for a community our size,” said Kyle Hannon, the vice president for public policy at the Greater Elkhart Chamber of Commerce. “Also, a New Horizons Band started a couple of years ago. It is made up of retired people who just want to pull their instruments out of the attic and start playing again.”

At Gemeinhardt, the workers, both in management and labor, really take their playing seriously. All 60 people at the company play an instrument of some sort, and the Chief Executive Officer, Gerardo Discepolo, is an accomplished flutist with a doctorate in musical studies.

“I am a flutist,” said Gemeinhardt marketing man Hutchins. “The fellow who runs the clarinet department went to Julliard. We are a musician-run company and we believe that is important for trust.”

The music business in Elkhart has also had some spin-offs. McBryde said that Blessing, for example, gets its primary metals from Anderson Silver Plating, which was founded in Elkhart in 1948, just as the boom in student instruments started. Jesse James Babbitt learned his trade early in the 20th Century at C. G. Conn, and 80 years ago started his own clarinet and flute mouthpiece business – the JJ Babbitt Company. Now the company, with just 40 employees, all in Elkhart, manufactures 300,000 mouthpieces a year, and is run by William R. Reglein, Jesse Babbitt’s grand nephew.

Still, Gemeinhardt, as other companies in Elkhart, has decided to “partner” with off-shore firms. Hutchins said that all the parts of its flutes and piccolos are manufactured in Elkhart, but a lot of assembly is done in Taiwan.

“We ship the parts over and then quality check the instruments when they return, so we keep that here in Elkhart,” said Hutchins. “But, yes, in order to keep costs down, we have decided to take advantage of what Taiwan and the rest of Asia has – cheaper unskilled labor. We keep the skilled jobs here.”

Hutchins said that the price point he and the other student instrument manufacturers in Elkhart have to keep is $20-25 a month for rentals. They sell their instruments to distributors, who then go to schools in hopes of getting those first rentals.

“After that, we hope to rent what we call step-up instruments – the next more sophisticated models,” he said. “You hope there is a third step, the one where the students go on long enough to buy the instrument.”

That, in turn, he said, makes the next generation rent, and the cycle continues. Fortunately, according to Hutchins, most school systems still support music education, and as long as that happens, it seems that Elkhart’s businesses will survive.

“The town is also a center for RV design and manufacture, and because Miles Laboratories – the originators of Alka-Seltzer – was an Elkhart firm, and is now owned by Bayer, there were drug businesses, too,” said Hutchins. “But the music business is in our blood here. It is an American manufacturing success story, and we like being a small part of it.”