By Emily Halgrimson

Today’s Machining World Archives January 2009 Volume 05 Issue 03

A St. Louis program focuses on manufacturing’s thirst for skilled CNC machine operators to elevate hard-to-place workers.

The Manufacturing Training Alliance (MTA) in St. Louis, Missouri, faces a daunting task — turning minimally skilled workers, ex-felons, and even the homeless into hirable CNC machinists. Although the MTA in St. Louis has been functioning for 10 years, it’s only in the past five the program has made a sizeable contribution to educating the industry’s workforce. Jason Taylor, a recruiter for Aerotek Commercial Staffing Company, says when he first started with Aerotek, he had about a 20 percent success rate with MTA graduates getting hired after the 90-day probationary period. They now have about a 65 percent rate. “It’s very good [quality] now,” he said.

The program, which has led more than 500 new workers through its 16-week advanced manufacturing course, started after a local boy was injured in a drive-by shooting. The community decided that there was a need to work with at-risk youth in the area. “There was a lot of gang activity going on at the time,” said Jonathan Bolden, the vice-president of the MTA’s Education and Training Department. But over the years, with the rise in layoffs, the MTA has started focusing mostly on adults. Some young people still go through the program, but the average age is now about 28.

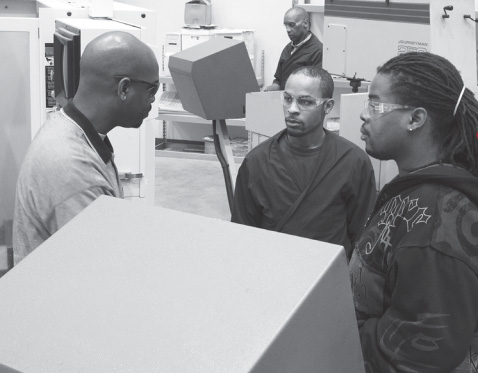

The MTA shop floor in the old Wagner Electric building on the run-down west side of St. Louis has nine machines in the shop. “We have two different types of mills and a 3-axis Tree-vertical machine. That’s what I like to start with. Then I step them over to the Vertical machining center where they get a chance to deal with automatic tool changers and different types of setup,” said Eddie Welch, the instructor of the advanced manufacturing class and a graduate of the program himself. The shop also includes a 2-axis horizontal lathe the students practice turning parts on.

The advanced manufacturing program teaches CNC setup and operation, and also has a prep program which includes forklift certification, OSHA certification and blue-print reading — completely free of cost. It also provides job placement and encourages its students to continue their education. “Even after you’re done here you can go through the CAD program and it’s all funded for you,” Welch said. “Then you have the background to continue into programming, master machining, or tool and die. This opens up a whole new world.” The 16-week course gives students the basics so they can get their feet in the door of the manufacturing industry. “You can learn theory in the classroom, but you have to be able to put your hands on it. Like anything else, it’s a skill,” Welch said.

The Loss of Jobs

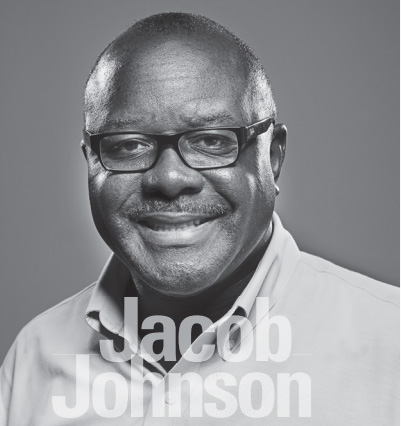

In 2000, when more and more manufacturing jobs were going overseas, many people wanted to shut the program down. “They said, ‘there are no jobs,’ and ‘we don’t think [the program’s] necessary,’ which told me that they didn’t understand manufacturing. Everything that’s not grown from the earth or drops from the sky has to be manufactured,” Mr. Johnson, the president of the MTA, said.

He believes that there will always be manufacturing in America but its necessary to be prepared for changes in the industry. “In order for us to compete we will need to automate and increase productivity,” he said. “And for minorities and women — it’s so hard for them in a downturn in the industry to even get in. Our program is 90 percent minorities and women. We target them.” There’s no other training institution in the region that claims to train people in advanced manufacturing for free, especially in 16 weeks.

There are approximately 1,300 new job openings a year related to manufacturing in the St. Louis area, and the MTA’s maximum training capacity is 120 students per year. So the MTA feels confident that they’ll be able to place 90 percent of those they train in jobs. “When you stop training and you start getting these contracts that are coming back from China and India, you must have a skilled workforce,” Mr. Johnson said. What works for MTA is the concept of getting people basic training and skills and finding them entry-level jobs in a short period of time.

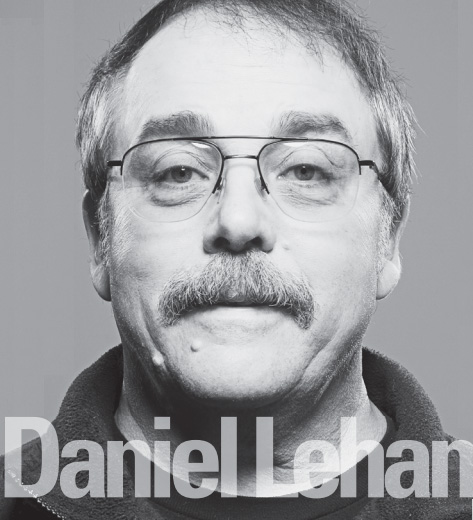

Daniel Lehan, a 60-year-old married man with grown children, was having trouble finding a job when he came across the MTA. “I was the tool designer for progressive dies for punch presses. You can’t find a position for that anymore. The economy’s so slow and they’re shipping all of that stuff over to China,” he said. After being laid off and unable to find work as a tool designer he took a job as a tool crib attendant. But the company made automotive parts and because of the recent economy, had to lay 38 people off — Daniel was one of them. “So I went ahead and got on unemployment. I knew it was slow, but I never knew it was that slow,” he said. In one of his job interviews they said if he knew how to operate CNCs he could be a part-time tool designer and then work on the CNC machines, too. So after seeing numerous ads for CNC jobs he thought he’d give it a try. “It’s worked out well because I have good math. Hopefully I can send out resumes soon with my graduation date, so they’ll know when I’ll be done. Then I’ll get a job really quick, because they place you here also,” he said. He’s hopeful he’ll get a job out of this but knows he’ll have to work at least another seven years before being able to retire. “Maybe 10 the way they’re talking,” he said.

The MTA claims to use the existing workforce/welfare system the way it’s supposed to be used. “When someone’s unemployed you find a way to give them a skill or some additional training so they can go back out and get reemployed,” Mr. Johnson said. All of the graduates finish with six credit hours at St. Louis Community College. “Some folks are the first generation college folks in the family. When they get that college ID I see a change in attitude. For a family that’s struggling and hasn’t had a lot of educational attainment, you go home and Mom or Dad are saying, ‘I’m a college student.’ It changes family attitudes about learning,” Mr. Johnson said. “That’s one of the biggest challenges: To change a blue-collar worker’s attitude about learning.”

Hope for Stability and a Livable Salary

Along with the lure of a higher salary, the potential for basic job stability attracts the students at the MTA to manufacturing. Earl Aitch III had a background in chemistry before landing himself in prison with a DWI. His hopes for regular salary increases are much higher after completing the program. “I’m going to get my experience where I have to, to get up there.” But he knows patience is necessary. “Nothing’s going to happen overnight. If I see a salary cap at any place then I know it might be time to, you know… put my resumé out there again,” he said. Even more important than salary for Earl knows he’d have a job in the future. “I’ve worked all my life, so money isn’t the biggest object right now — it’s stability.” Earl was in construction for some years, but wanted out of the back-breaking seasonal work. He’s willing to trade a higher salary for some regularity. “In a few years I can make at least $40,000, but that’s cool with me because it’s Monday through Friday and I get my weekends off, paid vacation and great health benefits. It’s the American way. That’s what you want,” he said.

Jason Taylor of Aerotek has two offices in St. Louis and focuses on staffing the manufacturing sector. He said that one of the reasons a company would look to hire from a place like MTA instead of a traditional vocational program or tech school is that a lot of his clients are looking to fill entry-level positions and a lot of the students who are coming out of the MTA are okay with making $10 or $11 per hour. “You go to some of the other technical schools in the area and [graduates] are looking to make $18, $19 or $20 per hour right out of school,” he said. Taylor says that’s just not realistic. “I’d say that maybe one out of 10 is going to find that job making $20 per hour. The individuals who come from [the MTA] I wouldn’t say are less qualified, but they do come from a different background, and they’re okay starting out at $10 or $11 or even lower, to get their foot in the [door at a] company,” he said. He thinks a lot of the manufacturing companies hiring right now appreciate that, and he thinks that some of these individuals will probably work even a little bit harder than some of the other applicants. “They have a little bit more to lose if they’re not working than someone who comes from a trust fund,” he said.

Eddie Welch says part of his job is placing students into companies that not only provide room for advancement, but also a livable starting wage. “A lot of companies come in offering $8 or $9 per hour and I kind of push them out the door, because you can’t live off that,” he said. The normal starting wage for MTA graduates is $12 per hour.

Who’s Hiring?

Even though the U.S. is experiencing record job losses, there are still people out there recruiting qualified employees. Jason Taylor of Aerotek has clients give a specific job description to him and he tries to fill that position. “CNC is one of our biggest [job openings] right now, actually machining all around,” he said. “We are most definitely finding an increase right now.” But he also says that the majority of the individuals who come out of the MTA pro-gram don’t start CNC jobs right away. “CNC is not the only thing we work with. We have other jobs like drill press, punch press and brake press, maybe something more entry level.” A lot of these individuals just want to get their foot in the door in some manufacturing company that maybe has a CNC machine, so that down the road they can move up to it, he said. Jason has been recruiting MTA graduates for five years and he says the training program has grown a lot. “They’ve turned it around. Quality has been phenomenal,” he said.

Eddie Welch thinks that the higher age of his students is attractive to employers. “We have an older crowd that has already been through that young stuff,” he said. “They’ve worked before and some of them have kids — so they’re more focused, even though they might have had a little trouble in their past.” He thinks that sometimes those life experiences make you humble. “If they weren’t already, they are now,” he said.

Connection to the Industry

One strength of the program is that the curriculum is based on what the companies who are hiring say they want in new employees. “We have an advisory board where a lot of shop managers come in month to month and actually tell us what they want and expect from their employees,” said Welch. As a result, the MTA is constantly changing the curriculum so the students are more marketable. “We don’t just teach the CNC operations here. We teach the set-up side of it too, so there’s a little more skill involved,” he said.

Nowadays the biggest trait employers are looking for is a strong work ethic. Welch can have someone who knows shop math, someone who’s had experience in the shop and knows blueprints, but a company won’t want that person if they aren’t at work every day, aren’t on time and aren’t reliable. “I give my students a little pep talk at the beginning of the class. A job is a job, I don’t care if you’re at McDonalds or wherever. You’re going to have to be there every day and on time, or you’re not going to have a job,” Welch said.

Jameca Harris is a young, single mother. She says that she likes that few women do machining. She’s also appreciative that the MTA offers job placement. Before starting the program she worked in the culinary field. “I wanted a change so I thought this might be interesting,” she said. She’s hopeful that she’ll find work. “I don’t know how easy it’ll be but I’m willing to do whatever it takes,” she said. She discovered the MTA through the Missouri Career Center. “A lot of people are out of work and it’s kind of scary. But I think in this area it might be a little easier to find a job,” she said. Jameca thinks that a lot of people who are competing with her for the same job may not have the same kind of training. “You know, we’ve got to do a lot of math and the others won’t have the same experience. Sometimes people are scared to go into a job because they know they don’t have the training. This makes you more confident,” she said.

Challenges

Challenges

Like any other program set on changing the fundamentals of people’s lives there are obstacles. The class starts with 15 students and after the first four weeks is typically down to 12 because of a strict attendance policy. “We work for the students but also for the employers, so when we send them to somebody they got to be ready to go,” Mr. Johnson said. “If you can’t come to class on time you aren’t going to come to work on time.” In eight weeks the MTA usually graduates seven and 90 percent of those are placed in jobs.

The students also have to pass a series of drug tests, which for many turns out to be a challenge. “We have two throughout the training. I guess they don’t have this true belief that the test will catch them,” Mr. Johnson said. “I’ve heard the excuses, but every employer will give them a drug test.” Even so, there are always some who think they’re going to get by. Some companies even give hair follicle tests, which will sometimes find traces of drugs from up to six months before. “For those employers, we know who we can send to actually get through the interview process,” Mr. Johnson said.

Ex-offenders face special challenges. “It’s a target population that has a lot of issues and barriers in front of them,” said Jonathon Bolden. “It’s really hard.” That’s one of the issues the MTA is fighting constantly: Finding employers who are willing to hire ex-offenders. Often employers say “we hire on a case-by-case basis,” but again and again the ex-offenders are sent out there and the door is slammed in their faces. “Those employers we have had success with — those are the ones we focus on,” Mr. Bolden said. But the MTA is always looking for new employers that will hire ex-offenders. It’s a constant recruiting battle.

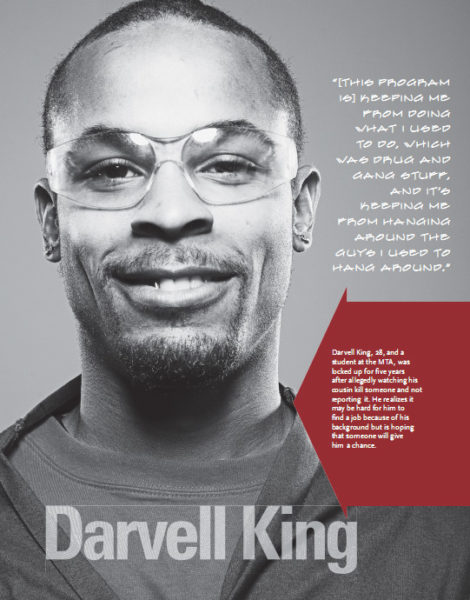

Darrell King, a 28-year-old man, has been in the program for 10 weeks. He says he was locked up because his cousin shot somebody when he was 12 and Darrell saw it. “I didn’t report it, but they said I was supposed to tell them. For five years I was locked up. Before that I worked in telemarketing, I worked for a country club, in fast food and a cleaning company,” he said. Darrell started a program in auto mechanics but didn’t like it. He knows it might be harder to find a job with his background because a lot of companies have zero tolerance for felons, but he hopes that someone will see his experience with the MTA and give him a chance. “This program’s keeping me from doing what I used to do — the drug and gang stuff, and it are keeping me from hanging around the guys I used to hang around.” You eventually get there, he said. “My grandma use to tell me there’s always a storm before the calm.”

Jason Taylor notes that there are some individuals he can’t help because many companies have strict policies when it comes to backgrounds. “A lot of the violent offenses, there’s just nothing I can do about it,” he said. In Mr. Bolden’s experience, many times when a company hires a violent offender, it’s a job where there are going to be other violent offenders. “And it’s going to be a job that may be quite demanding. You got to prove something, but that’s with any job,” he said.

Some recent grads get frustrated when looking for a job because it can still be really difficult to find one, especially if you’re an ex-offender. Welch tells the story of one young woman who can’t seem to get a break. “In my last class I had a young lady of 30 who was a violent offender, but she was 17 at the time. She really had a challenge to get employment. She had four kids and was a much different person. She could just not get that door to open for her.” As far as he knows she hasn’t been placed yet.

The Future

The Future

The MTA has seen steady growth since its inception, and it is believed that current layoffs in the U.S. will increase the demand for training. “We have a small staff of six, and I believe that with the current layoffs we will need to double our capacity and double our staff,” Mr. Johnson said. The U.S. Bureau of Labor predicts a rapid increase in the need for jobs in the coming years, and MTA people are hopeful that manufacturing may be able to step in to fill some of that need. The hope at MTA is that the new President will bring in an era of growth and stimulus. “There’s definitely a change around here since the election. You can see a bit more hope,” said Eddie Welch. Early on in the program the MTA’s grant was cut and the program was forced to close its doors for several months. “When the grant got cut the last time I was here. That was when we had just put Bush in office. They cut the grant that was training people that was working and generating tax money around here,” he said. “It was like, what do we do now?”

“This place is really changing lives,” Welch said. “I’ve had people in my class that were actually homeless.” One student was living under a bridge, and every day Welch let him keep his clothes at the school. “We have a shower back in the bathroom, and every day he’d come in and work and do what he had to do. Then he’d take a shower and go on back under the bridge,” he said. He eventually ended up going to work and bought himself a house and car. “It’s that kind of thing that makes me want to keep doing this,” Welch said.