What do you do if you are running a major pharmaceutical firm and a team of your employees comes to you with stunning news that an aging drug of yours, soon to lose patent protection, may be a treatment for Alzheimer’s?

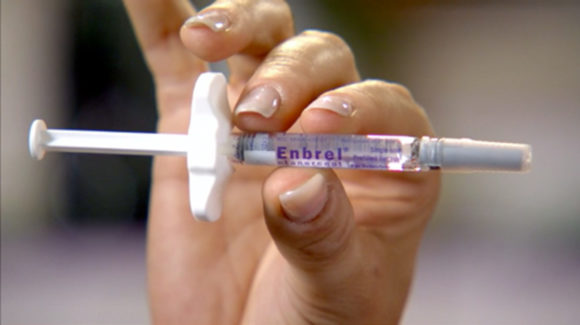

It happened at Pfizer in 2015. A team was analyzing death insurance claims for users of its products, including the rheumatoid arthritis drug, Enbrel. The computers were checking for the possibility that Enbrel might have had a peripheral benefit for its long-time users. To their amazement, they found that very few Enbrel patients died of Alzheimer’s. This was not clinical study data. The FDA would have laughed at it if somebody had brought it to them. It was serendipity, not science.

But for Pfizer, it might have been a clue, as crude as the data was, that Enbrel could hold a key to a treatment for one of the most awful maladies in the world. And they owned it–but only for three more years until the patent expired. Then it would be open season for the generic jackals in India and elsewhere to copy for pennies.

Researchers within Pfizer pushed for a massive clinical trial, at a major cost, to scientifically determine the effectiveness of Enbrel in preventing or at least slowing the devastating effects of Alzheimer’s disease.

Management spent three years mulling whether to pursue further studies. It was a long shot at best, they figured. None of the other research in the field targeting amyloid plaques had proven a statistical effectiveness when compared with pure chance.

The cost of a clinical trial on Enbrel as an Alzheimer’s treatment would be enormous. And what if it was the magic bullet? In three years, the generics would eat your profit. And if it failed like all of the others had, the stockholders, pension funds, and hedge funds would have your scalp.

In 2018, they killed the idea. Enbrel for Alzheimer’s was a dead issue.

There was insider outrage against Pfizer for not exposing their initial findings from the insurance data.

The American firm, Biogen, in collaboration with a Japanese drug maker, Eisai, did decide to continue their pursuit of a cure based on amyloid plaques. Last week, a major clinical trial for their patented drug finally showed a significant benefit versus a placebo.

It raises a terrible moral question.

Insiders at Pfizer knew about the Enbrel dilemma. By some accounts, many people in the company were appalled that Pfizer didn’t even come forth with the death claim insurance data, which might have pulled more firms onto the Enbrel path.

Pfizer never explained their reasoning for the decision. Most likely, money was the primary rationale. What would you have done in their position? The likelihood of success was remote. So many other efforts had failed, but they knew about the insurance claim data.

And now Biogen, who would not give up, has their drug, Lecanmab, which actually seems to work on the plaques.

In these situations, should the government step in for the greater good of the people? Should there be subsidies? Should patent protection be extended?

Is return on investment the ultimate issue for drug makers? What would you have done?

Questions:

Should there be government funded Warp Speed programs to cure ailments other than Covid-19?

What would you have done if you were in charge of Pfizer?

Note: Bob Ducanis, a long time reader and commenter of this blog, provided the idea and the impetus to write this article. Much thanks, Bob.

4 Comments

A boyhood friend of mine, born on the same day as me died of Alzheimer’s disease at 74. We were in Cub Scouts together. Norm’s Mom was den mother. We went to high school together. Norm was the team manager of the high school basketball team I played on. Reading the material Bob Ducanis sent me infuriated me and pushed me to do this blog for TMW. I think Pfizer at least had the moral obligation to publicize their insurance data on Enbrel and Alzheimer’s. It might have saved three years. Merck and Roche are close to disclosing positive research on their drugs. It is a race against death and misery.

Yes, Pfizer was wrong and we do need help from somewhere. My husband was just prescribed two drugs costing over $1,000 month and I have one that’s over $40,000/year. Mine gets covered by insurance but his are out of pocket. Thank you for covering such a range of interesting topics.

Lloyd,

I have had 2 close relatives and several acquaintances suffer with this disease; I believe it is harder on their loved ones. As to your question, I think it would depend on several variable factors.

I’m sure you are familiar with the Springfield Armory of the 1800’s, where government agents freely spread good ideas between every gun maker in the area. I’m sure it made it harder to dominate that industry, but was great for the country. And the big names then are still bankable brands today.

Maybe taking federal money to develop drugs should require something like a fiduciary designation, where the public good comes before or at least along with shareholder good.

Generics help the rest of the world run, yes maybe at the expense of the US consumer, but that’s only due to the relative greed of big pharma. Pfizer made 40 Billion in Profit in 2015. Their profit margin is 80%. There is room for them and other companies to make money, lower prices, and still help the rest of the world.