Today’s Machining World Archive: March 2006, Vol. 2, Issue 03

At first, Dan Miller thought the Saturday morning phone call was a late – and very bad – April Fool’s joke.

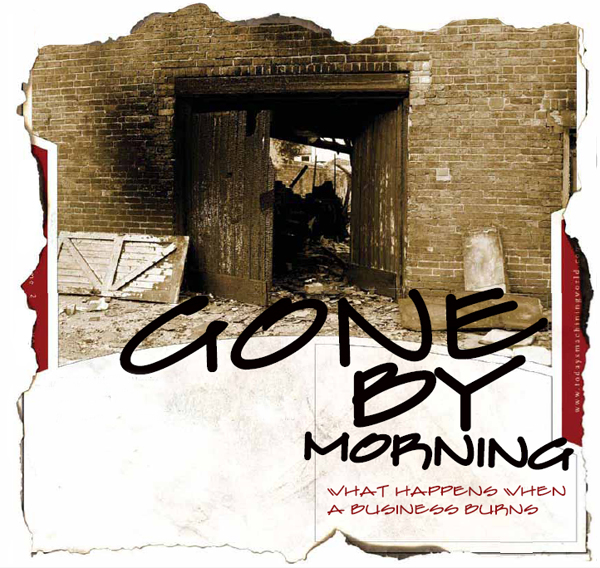

But, the April 2, 2005 call was not a prank. An employee was calling the owner of Extreme Industrial Knife, Inc., to say a fire was raging at the Salem, Ohio, machine shop. Reality sank in, and Dan Miller cried. He was certain his years of hard work had literally disappeared into the smoky air.

“I was totally devastated,” said Miller. “When I walked in and looked around, everything was covered in black. It looked like everything was on fire. I was out of business.”

The fire’s origin was at a critical piece of machinery in Miller’s shop, although the exact cause of the fire has not been determined. The CNC six-axis tool and cutter grinder machine had been running lights out the night of the fire, so no one was there to sound the initial alarm.

Miller knew the machine was so specialized that finding a ready replacement would be next to impossible. Soot and smoke had also impaired the shop’s other machinery. Maintaining the shop’s commitment of under-a-week turnaround for industrial knife sharpening would be impossible.

That day, Extreme Industrial Knife, located adjacent to the Quaker City Raceway, began its own race – for survival.

The situation Miller confronted is one that any business owner dreads. Prolonged downtime can result in cash flow disruptions. More important for the long-term, such disruptions can lead to the loss of business, as customers form relationships with new vendors.

For machine shops, the risk of fire is very real. Everyday production pits metal against metal in grinding, milling and other processes. As tools dull, friction builds up, creating a ready ignition source for lubricating and hydraulic oils. In mist form, oils are more easily ignited. The resulting fire acts like a blow torch and can’t be extinguished unless the fuel source or the oxygen that feeds the fire is eliminated.

Keith Domagala is engineering manager for Affiliated FM, a commercial property insurance company, whose parent company, FM Global, is known for its loss prevention research capabilities. FM Global statistics on insured companies indicate about 25 percent of all losses in machine shops are directly related to flammable liquid weaknesses. (Affiliated FM was not the insurance company used by Miller’s company.)

“Flammable liquids really drive fire losses in machine shop type occupancies,” said Domagala. “A lot of people think oils won’t burn, but when it’s atomized, you have all the fire you want. Whether it’s combustible or flammable liquid, once that liquid gets ignited, the hazard is really the same.”

The potential for fire damage is much greater with lights-out production because of delays in discovering a fire, according to Mike Angstadt, owner of DaBo-Tech, Inc., a Palmetto, Florida, distributor of special hazards fire suppression, control and detection products. Angstadt noted the phantom shift is the wave of the future, growing more popular as a means of countering lower labor costs abroad.

“That’s where they make their money,” said Angstadt. “It’s basically sheer profit. Even manned facilities are on a dramatically diminished scale. If only two or three guys are working, they can’t be in front of 70 or 80 machines. Once the fire starts and there’s no one standing right there, they’re never going to put out the fire with an extinguisher.”

Angstadt pointed out that it’s a balancing act between money saved in lights-out production and the increased risk of a fire going undetected until it creates significant damage.

“If the entire facility burns down, you’re looking at a quarter million to a couple million just to replace one machine,” said Angstadt. “Plus increased costs of replacement machines and increased cost of insurance.”

For Miller, 36, and his eight employees, the fire prompted a life-or-death struggle for the business. Manufacturing since 1987, Miller had relocated from South Carolina to his native state of Ohio in 2000 to open Extreme Industrial Knife. With sales of $750,000 in 2005, his company had developed ongoing relationships with customers across the United States in the plastic, paper, rubber and metal

working industries, providing prompt repair, sharpening and replacement of knives used in industrial machinery.

The morning of April 2, a total of 33 firefighters from six townships around Salem, midway between Canton and Youngstown, responded to the fire. The emergency call came at 8:10 a.m. Since the local volunteer firefighters were already gathered for a fund-raising breakfast, they were able to travel the 3.5 miles to the fire within seven minutes.

Firefighters quickly located the fire in an oil pit of the CNC machine and had the blaze under control in less than 10 minutes. Green Township volunteer fire chief, Todd Baird, said the fire had been burning for quite a while, although he was unable to pinpoint the exact time of origin. Four other businesses that lease space in the facility suffered smoke damage, along with the raceway business office, where Meow the cat, the track mascot, died.

When Miller arrived, he saw soot, dirt, oil and water everywhere he looked. The sight was terrifying. The odor of smoke was overwhelming.

Oily soot stuck to machinery like magnetized metal shavings. The sticky, corrosive mix filtered into machine crevices, blanketed ceiling tiles, crept into the light fixtures and dirtied snow outside the building. Water from fire hoses helped extinguish the fire but left puddles throughout the facility.

It could have been worse. An employee arrived at the shop for work in the morning and found it filled with smoke and fire. With quick action, the building was still structurally sound. But it was bad enough.

“It was like starting from scratch,” said Miller.

Miller and his employees, also known as the “Extreme Team,” banded together to try to recover the facility. They hired a fire damage restoration company. After the service ran up a bill of $50,000 the first day, Miller called a halt to the operation.

Then, Miller and his employees set out to do the dirty work themselves. Experienced machine operators in the area suggested techniques for restoring the machines. The Extreme Team hauled every single machine in the shop out into the yard. Using power washers, they meticulously cleaned stubborn soot from machine surfaces and components.

Because of the corrosive nature of the soot, actions often had to be repeated. They applied WD-40 on machine parts but had to reapply it just days later when the rust returned.

“We had to detoxify everything,” said Miller. “We had to clean up, re-wire, repaint and put back together everything – all that good labor stuff. We replaced insulation and put in new light fixtures. Geez, it took a while.”

After a solid week of work, the team started putting cleaned equipment back in the building. It took at least two and a half to three months before the company was settled in again.

Miller needed more than muscle power to deal with the heavily damaged key piece of equipment.

“When you have a fire and get a piece of equipment ruined, if you [bought] that equipment for $100,000 and you [depreciated] it over five years like we had, then you get next to nothing,” said Miller. “So you get rid of it and get a piece of equipment that’s even older cause you can’t find any other. Then, you purchase a piece of equipment at the end of the year.”

“You’re already down, and just because you had the thing depreciated and on the books, it looks like you’ve made more money than you did,” continued Miller. “You have to pay Uncle Sam his chunk. That was the worst thing.”

Miller had insurance, but didn’t receive any emergency money for at least three weeks. Nine months later, he was still awaiting a settlement with the insurance company as litigation proceeded on the fire cause.

The business was squeezed to the breaking point. Miller has no doubt he would have been out of business if not for an acquaintance, whose personal loan provided desperately needed cash flow during this time of hardship.

“We were very fortunate to get one machine up within a week, and we had very understanding customers,” said Miller. “We were also fortunate to get back most of our customers.”

Today, Miller said his operation is still not 100 percent, and the employees continue to cope with interruptions.

Before the fire, Miller didn’t have automatic sprinklers or any other fire suppression systems. He began investigating prevention products after the fire and settled upon a fire suppression system that encapsulates each machine.

Business owners like Miller are confronted with an array of fire suppression options. Nothing, however, can substitute for the first line of defense; automatic ceiling sprinklers, said Affiliated FM’s Domagala. In all, 90 percent of fire losses are controlled with 10 or less sprinkler heads opening.

Also important is training employees, whose actions can avoid and control loss. In addition, companies should consider flammable liquid safety interlocks and shutoffs to eliminate the fuel source. Affiliated FM’s Domagala also recommends special protection systems on high-value equipment. With orders of new equipment, Domagala urges business owners to seek less-hazardous fluid. Affiliated FM’s parent company, FM Global, is currently conducting research on water-mist type systems for protection.

One fairly new fire suppression system by Firetrace of Scottsdale, AZ, uses flexi-tubing and a pressurized delivery system of suppression agent, either water, foam, dry chemical or gas. Initially invented for vehicular and laboratory fires, the system was soon updated to protect other small, enclosed areas, such as machinery. Within a span of less than four years, the company has fire suppression systems in more than 10,000 machines worldwide, says Scott Starr, Firetrace marketing manager.

“With high-value equipment, you want quick detection and quick suppression using clean alternative gases like CO2 or Halon,” said Starr. “This approach quickly puts out the fire but does not contaminate the oil so you can get quickly back into production.”

Mitsubishi, ships all its EDM equipment to Firetrace for retrofitting with the suppression system. The minimally invasive system, which uses tubing to cover all potential ignition areas within the enclosed area, can be installed usually from $1,000 to $2,000 for smaller machines, said Starr.

Quick detection and minimal harm from the extinguishing agent are critical because machine shops seek to return to normal production as fast as possible after a fire, said Angstadt. He also said a big question in the industry is the use of cutoffs, since the potential for machine tie-ups and breaking of machinery parts exists during the shut down.

“Some dry powders are so fine, they get inside bearing surfaces and cause degradation; the machines don’t work as well, so you’re almost looking at replacement,” said Angstadt, who recommends cooling gases to his clients.

“I’ve worked with about half a dozen clients who’d lost machines to fire previously,” remarked Angstadt “After installation of the fire suppression system, there’s been a record of 100 percent extinguishment of the fire. And, there’s no downtime other than changing out bits, putting on a new fire tank and starting the machine back up, where it’s allowed by local fire regulations.”

For Miller, the April fire was his first. In his opinion, one is too many.

“Zero is a better number,” he said.