By Barbara Donohue

Today’s Machining World Archives November/December 2010 Volume 06 Issue 09

You can do a lot with what you have—and that doesn’t mean just your machines.

In these tough economic times you’re no doubt looking at how to bring in new business and increase revenue. As customers push hard for faster deliveries and lower prices, and move toward sending work offshore, what can you do to compete? Buying new machines may not be feasible, so what can you do to increase orders and raise productivity with your existing machines, without spending a lot of money?

Revival of a screw machine house

“We are not giving up on the industry,” said Matt Corcoran, president of Waterbury Screw Machine Products Company, Waterbury, Conn. “Rather, we’re focusing on what we’ve got here.”

A year and a half ago, Waterbury Screw Machine Products was definitely feeling the effects of the recession. In business since 1938, the company has been led by third-generation owner Corcoran since 1988. The shop, in the same location for many years, runs cam-type, single- and multispindle screw machines: Davenport, Acme-Gridley, and Brown & Sharpe. “Nothing is computerized,” said vice president Charlie Smith. The company makes products mainly for the electrical switch industry—lots of toggles, nuts and other small parts, primarily in brass. Surprisingly, 90 percent of their production is used in Mexico and Costa Rica, Corcoran said.

Smith, also a third-generation machinist, joined the company a year and a half ago. Since then, he and Corcoran have figured out how to breathe new life into the business and have seen revenue increase by a factor of two and a half. The changes they made could work for many shops that are feeling the pinch.

The right people

Corcoran and Smith restructured their personnel, building a workforce willing to work, pitch in, cross train on different machines, and stay positive. When the setup person for the 1 1/4” National Acme multi-spindle became seriously ill, Smith learned how to set it up. Then they made sure someone else learned. “The guy with 20 years on a Brown & Sharpe can train to be an Acme setup guy,” Smith said. “It used to be ‘my machine.’” Not anymore.

“They’ve got to have a sense of urgency: ‘We’ve got to get that machine back up,’” Smith said.

“We hire on attitude,” Corcoran said.

As sales have grown, the company has been able to hire, going from 24 or 25 employees to 43. “We’re providing good-paying manufacturing jobs in a down economy,” Corcoran said.

“We go on three principles,” Corcoran said. “We pay a fair wage, we provide good health benefits, and we understand that life doesn’t revolve around work.” Workers go to their kids’ games, for example, as long as they don’t abuse the privilege.

Stretch to meet the market

“We quoted parts that we previously wouldn’t have because they were too difficult,” Corcoran said. Now they can quote thin-walled parts, long parts, and different materials like steel and stainless steel in addition to the brass and aluminum they have traditionally machined.

“We run big or small orders,” Corcoran said. How small and how big? “From 50 or 100 parts, up to 9 million,” Smith said.

Tweak your process

Engineering the processes has cut cycle times. Smith pointed to a Davenport making small brass parts. This part went from a cycle time of 2 seconds to half a second. How? It had been using a steel-threading method, he said, so changing to a brass-threading method saved time. Also, he reduced the drilling time by half using a rotating drill instead of a fixed one.

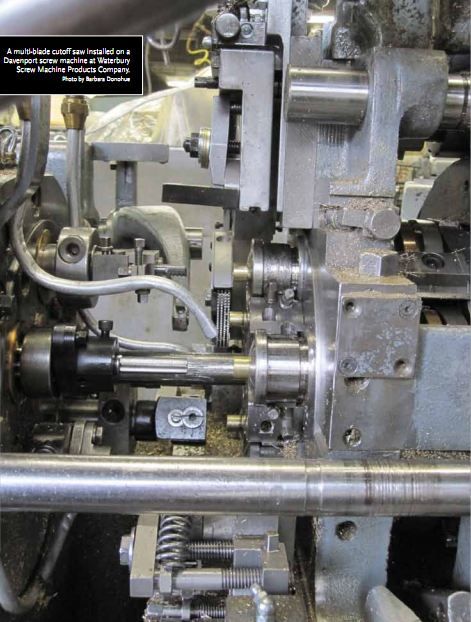

A thin nut made on a Davenport is now machined four at a time, connected end-to-end. Then a multi-blade cutoff saw separates them—so four parts fall per cycle. “If you can go from 1000 parts per hour to 4000, why not?” said Smith.

For flexibility, they plan tooling so a job can run on different machines. For example, one part runs on an Acme multi-spindle for large quantities and on a Brown & Sharpe for small quantities.

They look hard at machine setup time. On one machine, they got setup down to three or four hours, instead of two or three days, Smith said. He’s looking into using preset, datum-based tooling to help streamline the changeover process.

Up in the office, they’re bringing in software to help with scheduling.

Partner with customers

Waterbury Screw Machine Products is working more closely than ever with customers. Corcoran and Smith carry a Black-berry or iPhone in order to be available to customers around the clock. They make sure to stay in touch and spend face time with the customer when possible. Recently, Smith attended a customer’s four-day training session in Pittsburgh. Corcoran and Smith visit customers and customers visit them.

Partner with suppliers

They also pay suppliers promptly and work with them to maximize mutual advantage. For example, the company gives its tool business to LCM Tool, Waterbury, Conn., and LCM provides priority service, including one-day turnaround when needed.

Plating? “I’ve never seen parts plated so fast,” Smith said. For rush jobs he can get one-day turnaround as a preferred customer.

Metal is arriving all the time. The shop uses 25,000 to 35,000 pounds of brass per week, 2,000 pounds of aluminum and 2,000 pounds of steel. “We pay in 10 days,” Smith said.

By making the rest of their business strong, Corcoran and Smith pave the way for the machines to do what they’re capable of.

Old machines still at it

Across the country in Northern California, Tim Haendle, owner of Timson’s Screw Products, Willits, Cal., since 1975, also has a “quote-everything” attitude. “We don’t turn any-thing down,” he said. “We do the tough stuff. That keeps us alive.”

“We do everything—center less grinding, thread rolling, milling.” His number one customer makes air brakes for heavy trucks. Other customers come from the aircraft and valve industries.

Haendle runs 20 Acme multi-spindles and some Brown & Sharpe screw machines. The capacity range is from 7/16” to 6” stock. “We use the Acmes for taking material off,” he said. “We basically use our CNCs for finishing work.”

“Learn to run your old machines,” Haendle said. “There’s nothing wrong with them.” He talked about a 1 1/4” diameter aluminum part he makes for the gas valve industry. In 14 or 15 operations it’s hexed, slotted and thread-rolled.

“We’re talking a 10-second part, complete.”

A friend of his was taking a CNC machining class at the local community college, Haendle said. He gave the friend a complex brake system part he makes on a screw machine in 12 seconds. The friend showed the part to the CNC teacher who looked it over and said it would take two minutes to make—10 times as long.

“They’ve never proved to me they can make parts any faster,” Haendle said.

Haendle recently paid $499 on eBay for a used six-inch 6-spindle Acme from an East-coast bearing factory that was moving out of the country. One of his customers helped him find shipping for it that didn’t break the bank.

“I started with old machines and still have old machines.

There are 60- and 70-year-old machines still putting out product,” Haendle said.

Fixer-upper

Richard J. Marsek, president, Maintenance Service Corp. (MSC), Milwaukee, Wis., a rebuilder of large machine tools, has a rule of thumb: “Any machine that costs less than $400,000 new is not a candidate for a major rebuild, nor is any machine [whose rebuild] would cost more than 60 percent of the cost of a new machine.”

However, your machine might not need a total rebuild. “Money is needlessly spent on a total rebuild or buying new when only part of the machine is a problem,” Marsek said. “What is cost effective is attacking the problem areas of a machine.”

Specific issues will point to problems. Tolerances going out in a certain place show where the ball screws or ways are worn, for example. “If you have a problem with a clutch, we’ll find that. Noise? We put a quiet hydraulic pump in. We do smaller chunks and see if it solves the problem,” said Marsek. “You can spend $50,000 to fix the machine, instead of $500,000.”

Marsek has seen old-style machines used in very up-to-date applications. One customer in the nuclear industry had MSC rebuild a number of manual milling machines. The customer uses duplex milling heads to remove large amounts of material from two sides of the work pieces. “They are making high-end nuclear components on [machines] folks would laugh at,” Marsek said.

CNC for Brownies

Retrofitting older machines with a CNC control can be a cost-efficient option too. AMT Machine Systems, Columbus, Ohio, has CNC retrofits for Brown & Sharpe Ultramatic #2 or #3 screw machines. The CNC controls allow faster setup and operation.

AMT’s ServoCam UltraSlide provides CNC actuation of the turret slide, precisely synchronized to the existing camshaft. According to Greg Knight, vice president for machine tools at AMT, this provides a typical increase in productivity of 40 percent. ServoCam UltraTurn CL replaces all cams with CNC actuation and provides a servomotor spindle drive for speed control and indexing.

New CNC option for old-style Hydromats

Until the 1990s, Hydromat rotary transfer machines were, as the name implies, operated hydraulically. The company changed to a CNC format in the 1990s, said Kevin Shults, director of marketing at Hydromat, Inc., St. Louis, Mo. You couldn’t retrofit CNC on a hydraulic machine until recently when Hydromat introduced RS and SS controls.

The Epic RS controls up to three Epic tool spindles on one Hydromat machine, or a number of tool spindles on several machines. The retrofit includes a tablet computer with programming software installed. You program on the tablet computer and then upload the programs onto the tool spindle modules. The Epic SS provides control for up to six Epic tool spindles on one Hydromat machine.

Machines, but more

Yes, you may be running older machines, and maybe you wish you could replace them all. But even if that’s not in the cards right now you can still make the most of what you’ve got and keep the orders coming in and the parts going out. Some general principles can help:

- Make sure you have staff that is willing to work and think.

- Stretch the kind of work you’re willing to do.

- Partner with customers and suppliers.

- Continually improve your processes.

- Update, rebuild or repair equipment as needed.

You’re in the machining business, but there is a lot more to it than just the machines.

1 Comment

Excellent article……and inspiring.

As a shop owner since 1982, I have ‘aquired’ many older machines, and have been able to utilize them in some unique applications to efficiently make parts cost effectively.

A few stay set up for just one job. Sometimes clever can be just as profitable as investing in

the latest technology……or pretty darn close anyway….

dk