Today’s Machining World Archives March 2011 Volume 07 Issue 02

Interview by Noah Graff

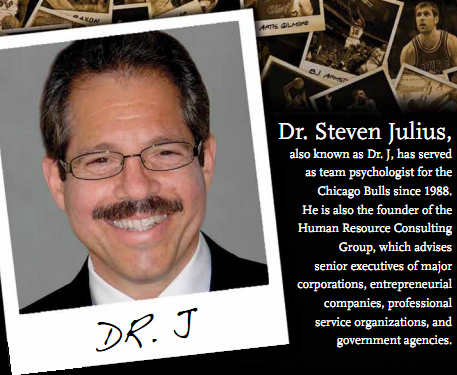

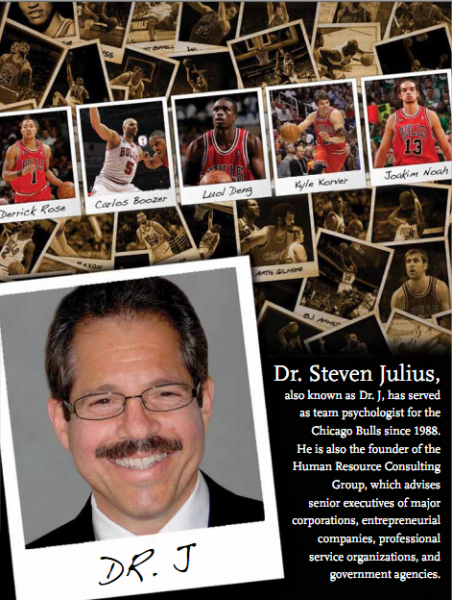

Dr. Steven Julius, also known as Dr. J, has served as team psychologist for the Chicago Bulls since 1988. He is also the founder of the Human Resource Consulting Group, which advises senior executives of major corporations, entrepreneurial companies, professional service organizations, and government agencies.

How did you become the Bulls’ psychologist?

SJ: I was brought in by a friend who had a relationship with the general manager at the time, Jerry Krause, to help out with some organizational issues. After that they began to ask me questions during the draft. It was the draft when Shawn Kemp, Stacey King, and BJ Armstrong came out. And from there the relationship simply grew.

So they wanted you to evaluate the players?

SJ: We evaluate players and determine their capabilities to not only make it in the NBA but also to adjust to going from high school or from a very short time in college straight into a professional job. The Bulls were one of the first teams back in the days of Tim Floyd to develop the Player Development Program. It helps some of the younger players with their adjustment so they can acclimate themselves, not just as athletes, but as independent self-sufficient adults in the pros. They learn how to manage their sleep, how to manage their money, how to find the right place to live, and how to manage their time effectively.

What does your job entail? Do you have therapy sessions with the players?

SJ: I spend the bulk of my time with the players, and even with the coaching staff, helping them on the mental aspects of the game—like managing stress, using performance anxiety as fuel rather than having it be like a stone tied around your neck, learning how to stay focused and to concentrate, and how to develop what we call “discipline persistence.” In particular, we teach players the importance of spending time dealing with the frustration of working on their weaknesses, rather than over-relying on practicing their strengths.

It must be a challenge to work with players who used to be “The Man” before the NBA but who now have to ride the bench.

SJ: Yes. One of the things we try to get across to these young athletes is that the time to work on their game may be in practice. They may not get a lot of playing time during the game. But every time they hit that wall and learn how to play through it or how to continue to practice as hard as they can as if it were a game, they are developing a level of maturity and emotional and mental toughness that will stand very well once the time comes for them to be in the game.

Do people come to you for help when they are in a shooting slump?

SJ: Oh yeah, over the years I’ve had people with shooting slumps come to me to learn how to work their way through it. It’s often not just physical, but mental. Sometimes they just have that momentary doubt because they are focusing on whether the shot is going to go in or out, versus figuring out how best to put themselves in position to take the right shot at the right time. All of sudden everybody starts worrying, “I’ve got to hit that shot,” rather than, “I’ve got to slice off that screen or that pick and roll just right so that when the ball comes I take my shot.”

Are the methods used to succeed in sports similar to those used to succeed in business?

SJ: It’s interesting that when I talk to the players as a group they’re more interested in hearing stories from the world of business than they are from the world of basketball. Just as the business [people] want to hear sports analogies. At first, I was a little surprised by that, but we all learn by example, and sometimes it’s easier to look a step or two outside of our own context to clear our minds and our biases and hear how things are done. Then we can reincorporate it into the way we operate.

What do you think of the old saying, “Chemistry doesn’t create winning, winning creates good chemistry”?

SJ: There are short-term [benefits] that come from winning that can overcome problems with chemistry. But over the long-term, there’s a reciprocal relationship between the two. It’s the mark of a good manager in business or coach on a sports team to recognize that the first thing you need to have to really get people to work together is a goal that they all can aspire towards. Something that’s emotionally elevating, that actually motivates people to sacrifice their individual needs for the good of the team. On really high performance teams, every individual on that team holds themselves accountable, not because they’re afraid they’ll be in trouble for failing, but because they’ll let their teammates down.