LG: Do you prefer to be called General Batiste?

JB: John. I retired two years ago.

LG: Was that an adjustment to be called John?

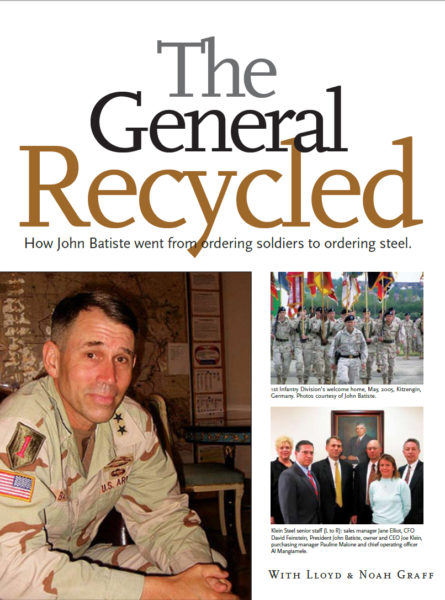

JB: It was a little bit, because for 31 years I was “sir” to everybody. But when I came to Klein Steel, I introduced myself as John, and it’s been that from day one.

LG: Can you tell us about the transition from managing 22,000 men in the First Infantry Division in Iraq in combat, to running a small-to-middle sized steel processor in Rochester, New York?

JB: I retired in November of 2005. I had worked in the defense industry, and there were options and opportunities that I could have elected to do if I’d gone to work for the big defense firms as an army lobbyist.

LG: Why didn’t you do that?

JB: I wanted to get to do the private, non-defense, for-profit kind of work, and I also knew I was going to speak out against the administration.

LG: You couldn’t do that as a lobbyist for the defense industry?

JB: I didn’t want to be encumbered with all that. So how did [this path] happen? There’s an organization in New York City called Leader to Leader [Institute]. Consultant Peter Drucker started it. One of the things they do is link retiring generals with the private non-defense, not-for-profit industry. Joe Klein, the CEO and owner of Klein Steel, had been looking for a president for about a year. He was at a retreat and ran into Peter’s No. 2, a wonderful lady by the name of Frances Hesselbein, and said, “Look, I’ve got this problem; I can’t find the right president.” She said, “I can help,” and within three days I was up in Rochester interviewing with Joe. I brought my wife up. We fell in love with the place. This company has everything I was looking for: integrity, high standards, and a focus on people.

NG: What was it like moving from an army base to the outside world of Rochester?

JB: You can live on-base or off-base in the Army, so we had bought homes in a civilian community in the past. But the people in Rochester received us really well. It was an almost seamless transition. It was easy. The family fell right into the city, right into Rochester, and everybody’s doing well.

LG: What are you involved in at Klein Steel?

JB: As the president, I’m involved with everything – buying; selling; operations, that is inventory control – taking the inventory, loading it. Processing is a big part of our business. We have burning tables, laser, water jet saws, angle masters, a whole range of processing capability.

LG: Did you know anything about the steel industry before you came in?

JB: I served for 31 years in an armored division, so I knew about artillery and a whole lot about steel but a different facet of the business.

LG: Hot steel.

JB: Yeah, in 2004, early 2004, when the 1st Infantry Division arrived in Iraq, we didn’t have very many armored vehicles. The thousands of Humvees and trucks needed to be protected, so I sent my guys out to Kurdish and Arab job shops to find steel and then get it cut, crudely but into the right shapes so we could bolt it on the sides of our trucks.

LG: So there are job shops in Iraq.

JB: Oh sure, mom and pop shops. You’d be surprised at how much steel you find. It’s all junk; I didn’t realize it at the time, but we picked the stuff up. It was a half inch thick of whatever chemistry, who knows. But they pull out their torch and cut it.

NG: They sent the Humvees down there unprotected?

JB: They were all unprotected with canvas doors or plastic doors, so we solved the problem ourselves.

LG: Which goes to the question of preparedness for the war. You were involved in some of the planning as an aide to Paul Wolfowitz.

JB: I was, early on. I left him in June of 2002, and the Iraq War started March of 2003. But I’ve been very vocal about this debacle for the past 18 months. I’ve testified five times in Washington. I’ve written many Op-Eds. I’ve spoke to many groups. We went about this totally wrong.

LG: Why was the intelligence so bad?

JB: I think this administration had a preconceived agenda to take on Saddam Hussein before they were even elected.

LG: So that overrode any intelligence that they may have had.

JB: Sure, it overrode all reason.

NG: Even before September 11?

JB: Absolutely, and I’m a Republican. It breaks my heart to say this. They were bound and determined to take down the regime of Saddam Hussein before they were elected into office.

LG: Wolfowitz certainly knew the background of Saddam Hussein and how he, through his tyrannical rule, was able to run Iraq with all the various factions. Yet you have the invasion and you have seemingly no expectations of what’s going to happen after Saddam is toppled. In retrospect, this is hard to believe.

JB: It is. The administration completely ignored the lessons of history. History books are replete with problems and examples of the challenges of this region called Mesopotamia. The British Empire had had a mess on their hands in the last century. It’s amazing they went back in with us. This region is so

divided. It’s defined by Arabs and Kurds and Sunnis, and tribes against tribes. They hate each other. There’s also an element of criminal activity that really resembles Mafia, gang warfare.

LG: At what point did you see it degenerating into a civil war?

JB: Our 1st Infantry Division was there in January of 2004. By March of 2004, we knew we had a budding insurgency on our hands that was rapidly metastasizing. The turning point for me was probably the elections of January 2005, where it became clear to those of us on the ground the high voter turnout rate had nothing to do with an appreciation for democracy. It was all about protecting turf. It was all about the Shia block voting one way, the Sunni block not voting in those days, and the Kurds who were deliberately changing the demographics around Kirkuk so they would own the oil for the future breakup of Iraq; it was important to them to have all that treasure.

LG: Do you see any chance of putting Humpty Dumpty back together again?

JB: Here’s the problem that we’re in now: I often equate a comprehensive national strategy to a four-legged stool. One leg is diplomacy, regional/global diplomacy to pull things together. Another leg is the political reconciliation work that has to happen, and that again is regional. It goes well beyond Iraq, and it’s global to some extent. Another leg is the economic reconstruction of this unbelievably poor country. Again, that is more than Iraq; it’s regional; it’s global. The fourth leg is the military. A strategy without all four legs will not succeed. The seat on this stool is what’s called “The mobilization of the United States of America” behind the important work to defeat worldwide Islamic extremism. That’s what it’s all about. This is not about Al-Qaeda in Iraq. Al-Qaeda-like organizations are in over 60 countries of the world and they’re gaining in strength every day. The problem is we have a failed strategy. It is dependent almost entirely on the military because the other three legs are ineffective and poorly managed with no leadership, and the country’s not mobilized in any way, shape or form. So I don’t know what the hell we think we’re doing.

NG: Is there any way to apply diplomacy with Al-Qaeda?

JB: It isn’t diplomacy with Al-Qaeda; it’s diplomacy with the rest of the region and the world. The fact that we don’t have a diplomatic mission in Tehran is unbelievable. The fact that we haven’t reopened our embassy in Syria is unforgivable. The fact that we haven’t designated a special envoy to pull together the moderate Arab nations in the region to be part of a solution is a tragic mistake. This administration doesn’t understand diplomacy. We haven’t done the work to politically reconcile the country. We haven’t done the work to economically rebuild it that needed to be done. There’s no indication in Iraq that they’re going to reconcile, and the Shia government in power is absolutely incompetent. Our guys are right in the middle of this and nothing good is going to come out of it.

LG: Do you think we are retracing the steps of Iraq now with Iran?

JB: Don’t know. But we need to proceed very cautiously. Iran is not Iraq. It’s a much bigger country, more people. It is homogenous; it’s all Persian. Most importantly, our military right now is in trouble. I was down at Fort Hood Texas last weekend, and what I saw was an army in decay. We can’t keep this up much longer. This is serious when you consider that there are problems out there in the world that we cannot respond to right now. We have no strategic reserve.

LG: I read a piece where you drew a parallel between the salesmanship that you had to use in Iraq with regional sheiks and local heads of clans, and the salesmanship that you have to use in the U.S. at Klein Steel.

JB: The selling skills with respect to steel as I’m learning them are not dissimilar to selling ideas that we sold in Iraq to political and military leaders.

NG: What ideas were you selling to people in Iraq?

JB: The notion that they needed to come together as one, that they needed to think of themselves as Iraqis first, not as an Arab or a Kurd or a Sunni or Shiite or a member of one tribe versus another tribe. They needed to figure out how to take their pain away, and it was something that they needed to do for themselves.

NG: Were you able to do that?

JB: To some extent. I used the power of persuasion lots of times in convincing them there was a way out of this morass they were in. In early 2004 there were examples where we were being successful.

LG: With General Petraeus and Ambassador Crocker, do we have the right leadership in place at this point?

JB: Dave Petraeus is a wonderful Army General; I’ve known him for years. I have a great respect for him. But there is no military solution in Iraq. Remember, he is just but one leg of this four-legged stool in this administration that has utterly dropped the ball in developing a regional strategy to combat worldwide Islamic extremism. Until this administration or the next develops that strategy, we’re in trouble.

LG: I’d like to go back to being in business versus being in the Army. One of the great catch words in American manufacturing is lean manufacturing. Do you think the Army is lean?

JB: I think that the First Infantry Division that I knew in 2003 to 2005 was about as lean an organization as you could get.

LG: In what respect?

JB: I was in Kosovo for 14 months, Turkey for four months, and Iraq for 13 months in that period working hard. There could be no wasted effort. There was no room for inefficiency because we were too busy.

LG: Tell me about the chain of command in the military versus the chain of command as it’s practiced today by you and the company you work for.

JB: There was a misconception at Klein Steel before I got here that I would be all about command and control, be very centralized and domineering and be very dictatorial. Nothing could be further from the truth. In the Army, the good units are very decentralized. There’s lots of input from subordinates. Great units are decentralized and leaders are not afraid of subordinates making mistakes because that’s how they learn. So my techniques today are precisely the same as they were when I was the Commanding General of the 1st Infantry Division. I value input. I want dissent. At some point there’s a decision made and then we all go do it, but up until that point there’s a freewheeling discussion, and during the execution of a mission it’s always decentralized to the lowest level. You give your subordinates what they need to accomplish the mission and you get out of the way.

NG: What’s the difference between the Army and civilian business?

JB: The biggest difference, and this is something that’s getting better and better at Klein Steel, is the element of discipline. That is to say, once a decision is made people proceed in that direction whether they agree with it or not. In private business that’s not always true. Talking to my peers in business in Rochester, there’s a tendency far beyond the decision point for passive aggressive behavior. The challenge of leaders is to figure out where this is going on, who the resisters are, and get rid of them.

LG: It strikes me that in the military, at least out in the field, you have to have built-in redundancies because people get hurt; they get killed; they leave. In lean manufacturing, one of the problems is lack of redundancy.

JB: You’re exactly right. There were multiple levels of redundancy in the military where you could plug them in all very quickly. In lean manufacturing, one person could make a huge difference if he or she is sick. Klein Steel is a very lean organization. As a Commanding Officer, I had a personal staff and another dozen consultants, from security people to cooks to take care of things. I don’t have any of that right now. It’s a lean organization in every respect. That was something I had to get used to.

LG: Do you think that’s necessarily good?

JB: It’s not bad.

LG: There’s a guru I’ve listened to a lot who always said, “Frank Sinatra didn’t move pianos.” The idea is that you should do what you do well and let other people fill in the holes.

JB: I certainly delegate as much as I can. At the moment I’m doing my own schedule, my own calendar, and answer my own phone. I think that’s okay; that communicates to people that Klein Steel still has an entrepreneurial ethos. It’s not extravagant. It’s not spending money where it doesn’t need to.

LG: Political question: Do we really want to find Osama bin Laden and kill him?

JB: Gosh, it would’ve been nice to get him in Tora Bora back in 2003.

LG: What I’m really getting at is, isn’t he a convenient symbol of terrorism?

JB: Sure, he’s nothing but a symbol, and he would be replaced multi-times over. You’ve got to remember, Al-Qaeda is a very decentralized organization. There are plenty of Osama bin Ladens out there. His legacy is going to live on whether he’s alive or dead.

NG: Is he a uniter for terrorists?

JB: Sure he is. But again, he’s going to unite whether he’s alive or dead. Do I think we need to get him? Yes, and I think that we diluted the main effort when we went into Iraq.

LG: Do you use the term “war on terrorism”? To me it’s a term that has lost its meaning.

JB: I don’t like that term at all. I prefer to describe it in terms of a struggle against worldwide Islamic extremism.

LG: I agree, and I think that this is a significant error that this administration has made, as well as most politicians. It has become a meaningless code to me.

JB: It’s meaningless, and on top of that, the nation is not mobilized behind it. So what are we doing? Yesterday I was at the Mittal mill in Conshohocken, outside of Philadelphia. Here’s this great mill that’s pumping out armored plate for the military. They produce a lot of steel, but a big chunk of what they do is armored plate for the MRAP program. But Mittal has no idea what the requirements are next year. It’s a big guessing game, and these MRAPs should’ve been built two years ago.

LG: What is MRAP?

JB: MRAP is the Mine Resistant, Ambush Protected vehicle the Army and Marine Corps are buying to protect soldiers. The industrial base is in no way mobilized; there’s no leadership at the national level to provide our soldiers what they need. There are something like seven companies now competing for the design of the MRAP, and what may very well happen is they’ll all get a piece, so there will be seven different designs and an unbelievable array of chemistries and thicknesses of armored plate that our mills have to produce, and that’s not very efficient.

LG: It’s very interesting talking to somebody who’s living in both worlds. It seems like you still spend a lot of time on military-related affairs.

JB: It’s difficult to escape. I find myself doing that kind of work at night and on weekends, 60 hours a week or more is Klein Steel.

LG: When you talk to clients, are they primarily interested in steel or do they want to talk to you about the war?

JB: It’s a combination of both.

LG: Did you expect that?

JB: Not when it comes out of left-field. I’m focused on selling steel and on relationships with customers.

NG: Does it get annoying?

JB: No, it’s not annoying. Part of this is educating the American people on what’s going on.

LG: Is the Army in decay or simply stretched farther than its real resilience enables it to be stretched?

JB: The two go hand-in-hand. I joined the Army after Vietnam in 1974 out of West Point, and my comrades and I spent 10 years rebuilding a broken Army. That’s what we’re facing now.

NG: From what I’ve read, you don’t think we should have a precipitous withdrawal.

JB: No, we can’t. It’s kind of funny, I’m a Republican and based on my campaign for 18 months, all of the Democrats think I’m on their side. It isn’t black and white. We cannot allow Iraq to fall into some huge humanitarian crisis. We can’t allow Iraq to be dominated by Iran. There’s strategic interest that we have out there. It starts with a regional strategy that we don’t have now, and from that there’ll be military tasks that make sense. For example, we may want to station troops in Kuwait for a while. We will have to protect whatever diplomatic mission we have in Iraq. We’ll want to go after Al-Qaeda like organizations wherever they are. Now that doesn’t mean that we have to put troops in Baghdad. But we have strategic interests in the world so we can’t just walk away. The other thing is, to leave Iraq will take at least a year of deliberate withdrawal. It ain’t going to happen over night.

LG: Do you think over the next year to 18 months this is going to all be decided?

JB: Or, it’ll be punted down to the next administration – which is really criminal, because more of the same equates to losing another 80 to 90 Americans every month, and hundreds wounded every month for no reason.

LG: Could you see yourself running for office?

JB: At the moment, no.

LG: Thank you so much, John.