By Lloyd Graff

Gary Pletscher hopped out of his Ford pickup at 5:55 a.m. on November 10thand marched across the Thielman Drive asphalt, anticipating a 13-hour siege of problem-solving amidst the whispering of new CNC Schüttes, stalling steel swarf, and the twang of dimes and quarters being won and lost every second on gear blanks and fittings soon to be trucked to Detroit.

Welcome to a day in the life of Curtis Screw Co. of Buffalo, NY, now in its hundredth year of cutting metal. Pletscher is one of 300 guys and 29 women in Buffalo who make Curtis make money in the relentlessly demanding world of zero-defect, give back the gains, just-in-time automotive sub-contracting. Curtis’ hourly struggle for perfection of product extracted from sometimes balky machines and overstretched people is both heroic and mundane — the boring daily grind of grinding tools, checking prints and fighting the tides of surging material costs in battered Buffalo, a factory town annealed by the competition for profit in the ruthless world car market.

Through the tenure of only four owners since 1905, and 50 years of co-existence with the United Auto Workers Union, Curtis survives, even thrives — family owned — because of the flat-out commitment of employees such as Pletscher, 32 years with the company, and planning to make it to 42 in Buffalo, his home since birth.

Pletscher, like many of Curtis’ people, has deep roots in the company. His father-in-law started with the firm in 1954. He became a Davenport lead man and set-up man. His brother-in-law works on Acmes and Schüttes. His nephew started in the plant a year ago. Pletscher was in the union for 26 years setting up multis, rising to lead-man and trainer. In 1998 Ed LeClair, Curtis Screw’s vice president of operations, approached him to join management as an estimator. “Our estimator at the time was retiring, so I went there for six months, and because it was crazy on the floor, they asked me to go into project engineering. After that, our maintenance foreman was retiring, so they asked me to head up that department. I did that for a few years. Almost three years ago they asked me to go to production supervisor on multis.”

Line of Fire

Now at 5:55 a.m. on a bitter, slate morning, Pletscher walks into Curtis Screw’s $9 million dollar gamble, the 150,000-sq.-ft. plant on Thielman Dr. The old Niagara Street and Roberts Avenue factories are systematically disgorging their machines to Thielman daily. Pletscher’s task is to ensure that production will never be interrupted long enough to cause a product shortfall to a customer. The job requires limitless energy, an encompassing knowledge of the big picture at Curtis, and a microscopic eye for the details that make jobs run and, sometimes, not run.

Moments after entering the new plant, Robin Johnson, the night supervisor, briefs Pletscher on issues he encountered during the last 12 hours. Pletscher checks the paperwork that documents the evening production. He looks for shortfalls and problems to report at the 8:00 a.m. production meeting. He walks down the line of multi-spindles already installed at Thielman, talking to operators, listening for the alien growl of a National Acme with indigestion. An old 8-spindle is suffering a high-low clutch malfunction that has slowed production on part #3394 from 9.5 seconds to 11 seconds. Have to get that fixed today. A part from Jelenic Machinery is due in later via UPS to fix another flagging Acme, running component #4167.

Pletscher walks over to the two brand new Schütte CNC multis that were installed in September. They are a big part of the $9 million bet that the owning Hoskins family, president Paul Hojnacki, LeClair, HSBC — their banker — and the whole Curtis clan have placed on their future in the metal-cutting business in North America. The Schüttes cost $1 million each, and they are dedicated to making transmission gear blanks that are not terribly sophisticated, but are one of the core products that Curtis makes for automotive. They run some of those jobs that go on and on and on, year after year, with big volume. The management team decided that the gear blanks were parts that they absolutely could not afford to lose, and they were going to buy the best machines in the world to produce the parts fast and flawlessly.

Both Hojnaki and LeClair told me privately that they preferred to buy Euroturns, the Czech machine sold by Maxim of Dayton, OH, but the key engineers at Curtis preferred Schüttes, which were considerably more expensive than Euroturns. In the end, they yielded to the engineers because they were going to make the machines succeed, if they staked their reputation on the decision.

Pletscher checked the numbers on the new Schüttes. He has some of his best operators on these machines. The CPK numbers were extraordinary in Germany, over 5. Jeff Kiepp, an engineer, went over to Cologne, Germany, for training. Schütte had service people on hand for weeks to qualify the machines. Ron Greco, a 27-year veteran, is running the machines on days, and Tim Kuta, who knows his stuff, is on nights, but they are machines, and they fail occasionally. Curtis can afford no failures on the $1 million Schüttes, so the company built its own dedicated part-checking machines to inspect each gear blank coming off of the CNC multis. The blanks roll down conveyors into the inspection machines. The inspection machines were designed and built by Curtis engineers P.J. Allen and Kenny Carmichael. They cost Curtis $46,000 each to make, but would have been $75,000 each to buy from a supplier.

More Than a Meeting

Pletscher needs the data on every machine at Thielman for the 8:00 a.m. production meeting led by Marty Nuara, the Niagara Street plant manager, who will run the combined operation at the new plant.

Pletscher wants to know what jobs are hot, what machines are ailing, what operators are available — everything — so he can match the right talent to the appropriate machines to get out the product. Curtis is able to juggle its customer requirements because it has depth of talent and equipment. They have built up extra inventory to cushion the move to Thielman. They haven’t missed a delivery schedule, despite the inevitable missteps inherent in moving machinery to a new location. But the moving process is hugely expensive.

The original working number was $3,000 per machine to move from Niagara Street and Roberts Avenue to the new factory. That figure was way too ambitious. With 200 major pieces, the move will probably cost $1.5 million at a minimum. Pletscher and Nuara have to keep an eye on every part number to make sure that no screw up is disastrous.

That’s why the 8:00 a.m. meeting is crucial.

At 8:00 a.m. Marty Nuara convenes the meeting at Niagara Street, the 100-year old headquarters plant on the Niagara River, overlooking the Peace Bridge and Ontario, Canada. It is seven miles from Thielman, but a century separates the multi-story downtown plant that has absorbed countless gallons of oil in its cement pores and the epoxy-floored — almost immaculate — new plant. Thielman somehow smells like Oreo cookies. Niagara emits the aroma of cutting oil, but after three seconds, who notices.

Gary Pletscher is on a speakerphone. Nuara runs the meeting at the big conference table near the kitchen. The supervisors plus Marty Schwarz, a 40-year veteran of Curtis who retired but came back to help with the move, sit at a table listening to Pletscher’s job and machine status report on speaker phone, then give their own update on their areas of supervision. They go over which machines are being moved and tell each other about every job in play at Thielman and Niagara Street. There is a problem with an operator with a bad absentee record. Nuara makes a note to bring the operator in for a disciplinary procedure. There are contract guidelines for such sessions. Curtis does not mess around with problems. They do not fester. This particular operator met with Marty Nuara that same day for a review.

Setting a Tone

Nuara is a young but seasoned 37-year old engineer who has moved up quickly at Curtis. He seems to live for this job. He grabs hold of problems like they are Lindt chocolates. My impression is that if Nuara ever had a couple of hours with no problems, he would invent one to tackle. Fortunately, for him, at Curtis, especially during a move, there are always plenty of issues to deal with.

Nuara is moving his office from Niagara St. to Thielman on this day. A few cardboard boxes prove adequate for his stuff; the wall photo of a pristine golf green will find its way to his office in the new building, as will his collection of favorite screw machine parts that he has collaborated on. I think every guy in the turned parts business has a treasured assortment of steel, brass and aluminum objects in a dish or drawer that symbolizes his life’s labor. To his wife or secretary they are shiny, hexagon flotsam, but to a real screw machine guy they are his jewelry, worthy of being frequently touched, even caressed.

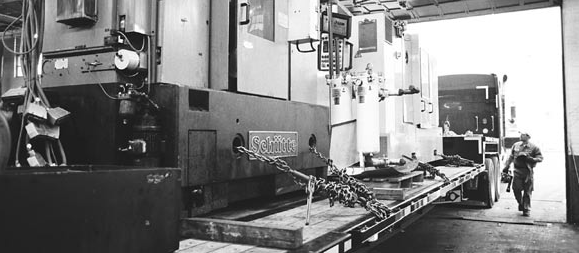

Underneath the second-floor conference room at Niagara St., the riggers are loading a 42-millimeter 6-spindle Schütte on to a flatbed for the trek to Thielman. A few hours earlier, it had been disconnected from its electricity and plumbing. Frank Augugliaro handled the job. Frank is also the UAW union chair at Curtis, a position he has held for six years.

Augugliaro is a pragmatic guy. He has worked at Curtis for 32 years. Curtis has 11 pay grades for union workers. He is in the top grade. Though Curtis is union, it has very few of the rigidities you see at a Ford or GM plant or, worst of all, McCormick Place in Chicago.

Augugliaro has a good working relationship with LeClair, but you do see clear boundaries between union and salaried workers. Management wears oxford shirts and ties, though engineers do not wear ties, generally.

When it comes to how the union works at Curtis, Augugliaro describes it this way: “If a guy has a problem, he’ll come to me, and we’ll talk about it. We’ll look at the problem, and if he has a grievance, then it’s up to me to go to management and talk about it. We don’t have a lot of that, but it does happen. Same thing if you have a guy that is being brought in for disciplinary reasons. I’ll know what happened in that meeting, why they are getting together. Things like those. ”We don’t really have an apprenticeship program here, but everybody here is cross-trained,” continues Augugliaro. “That is how guys come up. There are eleven pay grades in the system. One is the lowest and eleven is the highest. I am an eleven. Those grades are based on how you test, your experience, and how long you’ve been here. I’ve been here for more than 30 years, so that makes a difference. But if you learn your job and the jobs of others, you have an opportunity. That is the one thing that I tell every guy here. You have an opportunity. You have to take advantage of it. And there is almost always overtime. We don’t have mandatory overtime here, but if guys want it, they can take it. ”Augugliaro is a team guy. He negotiated hard on health insurance coverage, (100% paid by the company) but he has a strong interest in Curtis being successful. He is very happy that the company is making the investment in the new plant.

As important as the Thielman building is, the purchase of the four new CNC Schütte multis is perhaps an even bigger symbol of its commitment to the future. The company was almost completely out of space, which had to eventually be addressed, but they did not have to buy the fancy new CNC multis to run gear blanks. Investing in the sophisticated new screw machines was a sign to the employees that Curtis was really going for it, and they were doing it right here in Buffalo.

Both Hojnacki and LeClair had fathers who were union men. They are Upstate New York guys, not Harvard MBA’s. The Hoskins family lives in Buffalo, and John Hoskins, Jr. is working daily in the company. For a guy like Augugliaro, this is comforting.

Paying the Price

While the production meeting was droning on, Lynn Leas (pictured above), purchasing manager, was checking on steel pricing and deliveries. Basic prices for 12L14 have gone from 33 cents per pound to 65 cents during the year. Curtis cuts primarily steel, though aluminum is gaining share as steel prices continue to escalate. Leas is dressed in pink, from her Adam’s-apple-covering turtleneck down, short hair, piercing eyes and a verbal tone that says “don’t mess with me,” without ever having to say it. She has a degree in psychology. She’s been doing purchasing for 16 years, and knows the suppliers well. Curtis’ primary supplier is Laurel Steel of Burlington, Ontario, which is run by Lane Pate, a 40-year pro. Curtis is also a partner of Laurel’s in a non-leaded steel product that competes with 12L14.

She commented about her suppliers, particularly Laurel. “Lane Pate has been pulling his hair out about the price increases in the market,” she notes. “If Lane didn’t see it coming, certainly I didn’t. They said prices were going to go up in 2004, but we never could have anticipated this.

Never. So you’ve got guys going for their Social Security and checking their pensions, steel sales people, because they just can’t stand the pressure. I’ve heard guys say ‘I’ve been doing this for 40 years, that’s enough, I can’t take it anymore.’ The pricing is one thing, but it’s promising deliveries that are not forthcoming, because the mills are just booked solid.”

I asked her if she plays golf, because I know that golf and selling steel go together likes horses and manure.

“No, the steel guys don’t take me out golfing. I don’t golf,” she says. “I do an occasional lunch, but I don’t fraternize an awful lot with salespeople, and I think that’s a good thing. I don’t want myself, or my company, beholden to anyone.

I have very good friendships in the steel industry, but I need to be prepared at any moment to sever the business relationship, and I want to be comfortable doing that.”

Putting A Plan In Place

At 10:15 a.m., Hojnacki is driving from the Niagara St. plant to the new Thielman Dr. operation. It takes 10 minutes in his Lincoln Navigator SUV, but it has been a long journey to get into this building. Paul has had his eye on this plant for several years. He knew that the two old buildings that Curtis occupied were inefficient, cramped, and impossible to keep clean and lean. Thielman had been occupied by for Trico, the windshield wiper company. The building was a great fit for Curtis in almost every way; 150,000 sq. ft. of pure, open space, allowing 20,000 ft. for expansion — extra land for future growth, high ceilings, heavy floor, adequate office, accessible location for employees. It was built in 1991.Hojnacki had told the owner that he would be interested if it ever came on the market. The building opened up last summer and he gulped, because the timing was not quite right. Curtis was recovering from a difficult 2002. He figured that buying the building in 2005 and moving late in the year would be perfect. He told the building’s owner that he was interested but not quite ready, and asked him to give him a heads-up if another company was hot for the building.

Hojnacki is a planner. He is meticulous. When you meet him, you notice every blond hair on his head is perfectly combed; his shirt is unwrinkled whether it’s 6:00 a.m. or 6:00 p.m. One employee described him as a “neat freak.” He does not leave things to chance. He keeps a second pressed shirt in his closet for afternoon meetings. Before we met in his new conference room, he did a quick polish of the wood conference table himself. One can imagine him practicing 10, 12, 14, 16, 18-ft. jump shots by the hour when he was playing basketball for Buffalo State College in the early ‘80s.When the Thielman building hit the market he developed a business plan to present to the Hoskins family. The treasurer of Curtis, Stan Kaznowski III, was experienced in putting together financing packages, having done it for the earlier expansion at Roberts Ave. and the 1998 purchase of Sheldon Precision, a Swiss screw machine company they own in Connecticut.

Curtis already had a strong banking relationship with HSBC, the dominant bank in Buffalo. Kaznowski arranged a $600,000 grant from New York State and $1.05 million from government agencies at fixed low interest rates, plus tax incentives, property tax abatements from the county, and discounted electricity. The building was in an Empire Development Zone, which meant that they would pay no sales tax. Eliminating redundant people by consolidating two buildings would pay the mortgage.

So Paul and Stan figured out a way that Curtis could pay for the property if the Hoskins family would say “yes” to the project. The seller of the building was true to his word. Another buyer wanted the property. He told Paul that he had to have an answer. Hojnacki knew that the Thielman plant was an enormous opportunity. Building from scratch would take more precious time and be even more expensive. He knew that Curtis must buy this plant even if it was a year too early. Hojnacki had been talking to John Hoskins, Jr., the son of the owner, about the need to consolidate and move the company ahead. John Jr., now 34, has been working at Curtis for five years in several capacities, and gets along well with Hojnacki and LeClair, who run the business.

Hojnacki knew that Hoskins Jr.’s support would be essential in getting, John and Sue Hoskins to back the decision to buy Thielman Dr. John Hoskins, Sr. had bought the company from his wife’s father, Harry Smith, in 1977. But he had been pulling back from management of Curtis for 12 years, and rarely came in.

So last February, Hojnacki and Hoskins, Jr. traveled to Florida to visit the elder Hoskins’ to convince them that, at the age of 64, they should bet the company on buying Thielman, consolidating the two Buffalo plants and, by the way, ante up for four brand-new CNC Schüttes at a million bucks a pop to run the core product, transmission gear blanks.

With John Jr. at his side and the thorough business plan to justify the timing, Hojnacki won their support. A few years earlier, when John Jr. was spending most of his time singing with his rock band in a room right over the Roberts Ave. factory, this scenario might have played out differently. But with his son now a player in the company, and Hojnacki confident about the future of Curtis, the Hoskins’ family blessed the project. Hojnacki and Hoskins ascribe to that “grow or die” view of business. John Hoskins had bet big in ’77 when he borrowed the money to buy out his father-in-law. He bet the company in the late ‘80s when he bought 13 Hydromats to make fuel injector housings by the tens of millions, and at 64 he bet again on Hojnacki and his vision. My impression is that Hojnacki has the complete confidence of the Hoskins family. I can only speculate that the family also made a tacit calculation that to keep him on board long-term, they had to go along with this plan. A guy like Hojnacki, at 42, is a hot commodity for the headhunters.

“Grow or die.”

All in a Day’s Work

When Paul arrives at Thielman, he receives a progress report on the chip-handling problem they have been struggling with since the installation of the in-ground chip system. One of the big productivity improvements in the new plant will be the elimination of the onerous, oil-spilling, hand-pushed chip carts that plague the old Niagara and Roberts factories. Trenches were cut into the floor at Thielman, and a state-of-the-art chip-removal system by Mayfran International was installed. Unfortunately, it has been troublesome so far. The Mayfran man has been virtually living at Curtis for weeks, debugging the apparatus. Meanwhile, the steel swarf still gets stalled on its way to the massive crusher and spinner, which are to extract the cutting oil for reuse in the screw machines and prepare dry, salable chips for the scrap processors. It appears that the harpoon in the trenches needs to be changed to a smaller size to push the stalling chips and oil to the final destination.

Mayfran will get it right, or they will not get paid. Soon an InterSource chip system will arrive to process aluminum. The two metals must be kept pure of one another.

Mayfran will get it right, or they will not get paid. Soon an InterSource chip system will arrive to process aluminum. The two metals must be kept pure of one another.

Hojnacki confers with Bob Filipski, maintenance manager, who has been bouncing from one issue to another since 5:30 in the morning. Filipski is the point man for the move to Thielman Dr. He is an organizational sorcerer, juggling contractors, Curtis employees and fighting the fates to make the move work. The original plan to move four or five machines per day has been scaled back to two per day, and that is ambitious, while keeping the production going. Bob is a workhorse. He has a degree in electrical engineering and an MBA. He prepared a 3,000 line item plan for the move, which has been shelved for now. At this point, he is valiantly enduring the burn out of 14-hour day after 14-hour day, hoping to be able to go to Disney World with his 6- and 8-year old kids before the end of the year.

At 12:30 p.m. at the Roberts Ave. plant, an informal meeting of engineers and foremen is dealing with a situation. There is a hot job that is being run. It must be shipped the next day.

The problem is that the proper dunnage, the shipping-storage material specially made for that part, is not on hand. Without it, the parts quickly stain from the oil residue. The customer may refuse oil-stained, non-conforming parts.

Larry Krajewski, engineer, along with Brian Boneberg and John Englert, confer in a cubicle near the conference room. Should they suspend running the part until the dunnage arrives? The problem with that idea is that they have no open machines if they get behind, and it could mean another set-up. They consider a gamble, using temporary, improvised dunnage that is for another part. Nobody has a better idea at the moment, so they dispatch troubleshooter Krajewski to jerry-rig the dunnage.

At 1:30 p.m. at Niagara St., three guys traverse the labyrinth of the 100-year multi-story building to get to the fire escape overlooking the Niagara River and Peace Bridge to Canada. This view of the water and the occasional stunning sunsets is one the insiders’ perks at the old factory. Some of the Niagara veterans are already mourning the loss of their special views and the summer strolls to the nearby marina for a hot dog at lunch.

Moving is a gamble. Aside from the money, Curtis faces a cultural challenge that Renee Terreri, the head of human relations, is acutely sensitive to. Niagara St. has been the elite plant, where the headquarters is located. The expensive Erie-Swanson assembly machines are there. The CNC turning equipment is there. There is a slightly different attitude from one plant to the other — more direct supervision at Roberts, while Niagara has the expectation that the experienced men on the floor can figure things out.

I am reminded of one of Parkinson’s Laws, the pithy observations of British writer C. Northcote Parkinson. He believed that jerry-built, improvised old plants were more productive than highly organized new ones. Part of Hojnacki’s plan to pay for Thielman is to eliminate up to 50 redundant jobs, which could save $3 million per year. Some of the job losses will be temporary employees, and some will be salaried. No operators will be pruned. Terreri expects several retirements from people who do not want to deal with the change. She is now dealing with complaints from men who have already made the move who object to a new rule about garbage can placement on the shop floor. At the old plants, every man had his own garbage can. At Thielman, one can serves two operators.

The Thielman factory area has no windows, no river, no fire escape. It does have a beautiful eating area and green tiled locker rooms for men and women. There will be tradeoffs. Many guys are complaining about a 10-minute longer commute. Chuck Fischer, 35 years with Curtis, runs a chip system. They won’t need his job at Thielman, but he has been invited to stay on in a different capacity. He may just hang it up.

The Corporate Quilt

Back at Thielman, Hoskins, Sr. has arrived because there is going to be a photo shoot for this article, with employees who have other family members in the company. Hoskins looks fit, and is welcomed by many of the veteran employees who are working in the plant, as well as others who have arrived for the picture. There is a sense of the long-gone star player coming back for an alumni basketball game at the old high school that has just built a new gym. There is still familiarity with the people, but you start to feel like an outsider at the institution where you used to be the star.

A significant portion of engineering and management of the company have a military background. Most of the staff is from Buffalo. People stay a long time and develop friendships. They have family ties in the company. It is a beautiful thing to feel the tightly-knit fabric of Curtis of Buffalo, 100-years old.

Moving Forward

After the photos are over, we move into the Thielman conference room for an interview with Hoskins, Sr. He is modest about his achievements in building the company. He is more comfortable talking about his leadership of the advisory group of citizens who make key decisions at Buffalo State University. Hojnacki talked more than Hoskins did about the direction of the company. I ask John Sr. about the company’s dependency on automotive work. The essence of his reply and Hojnacki’s amplification is that they do automotive because they are good at it, and had geared up their capabilities to such a high level that automotive volume was just about the only work that they could do and still make money. The strategy was to add more volume to stay ahead of the overhead cost creep.

I found this interview the most disquieting time I spent at Curtis. Hoskins Sr. and Hojnacki were committed to automotive. Or were they both just stuck with automotive? The company mantra they reiterated was “grow or die,” and I am thinking, why not “change and live,” or “diversify and prosper?” Curtis is brilliant at what they do well, which is high-volume, high-precision, 100% in-spec automotive components. And in 2005, they are clicking with good orders and amazing efficiency, yet Hojnacki, LeClair and their head of sales, Greg Gutowsky in Detroit, are living the nightmare of continually fighting with their best customers to allow them to pass through their appalling increases in raw material costs. Curtis has spent decades building their relationships in automotive. Programs are planned several years in advance. Big Automotive and Tier One have cut back on their vendors. Curtis is on the short list and they depend on each other. And right now they are in a painful, strenuous wrestling match, which they are both losing, over the pricing of components. Paul, Ed and Greg know that if they cut their margins, they could fail. The buyers threaten that they will not accept increases. If Curtis loses their programs they could fail. It is a mess. Every day feels like being in the Roman Coliseum of Detroit. Hojnacki checks the Wall Street Journal and American Metal Market when he comes to work to see if the metal prices have changed.

When your business is cutting 100 million perfect steel pieces each year, every steel penny is huge. So here they are at Curtis, locked into the domestic car business, moving into a new building, paying off four new million-dollar Schutte CNC multis and dueling with their best customers over raw material wounds that they have no control over.

“Grow or die?” Maybe that is why the Hoskins and Hojnacki interview felt uncomfortable for me.

Engineering Solutions

It is 3:00 p.m. and Kenny Carmichael, head of engineering, is trouble-shooting an assembly machine, which was recently moved into the new plant. Kenny is one of those mechanical savants who have the gift of understanding how machines really work. He can fix anything, build anything and think it is the greatest privilege to get paid for doing it. He is one of the “glue” people who hold Curtis together when the dark forces are pulling it apart. Hojnacki and LeClair regard Kenny as a kind of company treasure, preferably to be hidden from outsiders’ view, someone who almost magically heals machines and solves manufacturing problems.

Today’s problem is a few alien parts, which were shipped to a customer without the required spanner wrench holes. It is a bizarre problem because there were only a couple of bad parts, but it has happened once before, and the customer is furious. The customer says they are going to require every new part to be inspected by an independent inspector for an additional 10 cents per piece. Ouch

Kenny knows a solution to the problem. They must build a part-specific inspection machine so this will never happen again. They can do it. It just costs money and takes time. This kind of machine is something Curtis is good at. They have a young engineer named P.J. Allen, who is getting to be pro at designing and building these. Making such machines could even become a new profit center for Curtis if they choose to share their expertise. Carmichael recently took a learning trip to the Iscar cutting tool plant in northern Israel. Iscar’s facility is brilliantly automated, enabling them to export $500 million worth of highly competitive cutting tools around the planet. Kenny is a person who has a variety of interests, from machining to jazz to military history. He is a former Marine with the demeanor of the proverbial Sunday-School teacher. For him, Thielman means lots of new fun things to do, and more opportunities to learn all kinds of good stuff.

It was Carmichael and other engineers who convinced Hojnacki and LeClair to buy the new Schütte CNC multi-spindles. They have several Euroturns in their plant, but the engineers prefer the solidity of the Schuttës and find them easier to repair. When the decision had to be made on the buy, management deferred to the people on the floor, particularly Carmichael. It speaks volumes about the decision-making at Curtis and throughout the machining world that I know. The successful firms use a collegial decision-making process. The operators, set-up people, engineers, maintenance staff, all contribute to buying decisions. Top-down, authoritarian decision-making usually fails in the long run. Very often, decisions are tossups, so it is up to the people on the floor to make them work, no matter which way they go. Curtis seems to live by this approach.

Carmichael described his role at Curtis as being a mentor to the other engineers: “One rule that I try to have for myself is not to solve problems alone, but have someone with me go through the process so they know the problem-solving process, and then, they not only get the result, but know how to get the result next time,” he says. “Then I try to develop the engineers instead of being what a traditional engineer is by nature — quiet and working alone. I want a team that can support each other. I’m fairly hands-on, but what I try to do is get the engineers to do it. I try to get them to be mentors of operators to push down the information and abilities.”

Carmichael accompanied Paul Hojnacki on the recent Precision Machined Products Association trip to China, so he understands the challenge of Chinese competition. He has traveled widely in Europe and observed sophisticated shops there. Curtis is continually looking for innovation in the super-competitive environment they work in. With the consolidation of the plants at Thielman, the company will have 20,000 sq. ft. of vacant space to grow into. Cutting redundant workers will help pay for the move. Using the open space profitably confronts Hojnacki, LeClair, Carmichael and the sales staff.

Constant Competition

Hoskins, Jr. and LeClair told us several times that Curtis’ competitive advantage is its ability not only to make machined components of consistent accuracy, but to deliver assembled components to its clients. Through the years, Curtis has invested in sophisticated assembly machines from Swanson-Erie Company in Erie, PA. These machines may cost several hundred thousand dollars to buy, but the payback for Curtis, with its high-volume automotive assemblies, is immediate. Curtis needs to find more of this kind of work, because it is relatively invulnerable to foreign and domestic competition. Automotive likes the assemblies because it simplifies their lives .I can imagine opportunities for assembly of high-volume parts of this nature in medical, telecom and military work, for example. So far, Curtis has stuck to automotive. It will be interesting to see if the sales operation will be able to use the leverage of assembly capability to push beyond purely automotive-related business.

At 4:00 p.m. a quality meeting is breaking up at Roberts Ave. Joe Manzella is director of quality at Curtis. He has held this job for 18 months, since coming from Siemens in Virginia. He is from Buffalo, and glad to be back home. He has lived in automotive throughout his career. He considers automotive the Major Leagues of the machining world. Super competitive, no defects allowed, tight pricing — bring it on. He says it was easier at Siemens because they were the big guy who could squeeze the Curtis-type vendors. But having worked on both sides, he knows what a company like Siemens goes through with its customers and suppliers. He knows the pressure on top managements, and he knows how one bad 25-cent part can be a nightmare for a company like Siemens or Ford. Manzella works closely with Rob Gauchat in sales to meet the needs of clients. It may be paperwork and documentation that keeps a customer happy, or the knowledge that Curtis only uses the best steel available. Manzella’s title may be quality, but he is a critical member of the sales team also.

Manzella is going through seemingly endless PPAPs as they re-qualify parts after moving to Thielman. In some cases, the big customers are total sticklers, and in others, they are more trusting of Curtis’ professionalism, and cut them a little slack if a label is occasionally missed, as long as the part is to the print. Manzella knows the game, and is unstinting in pushing the zero-defects mantra on the floor. After all, this is the Major Leagues.

At 6:00 p.m. at Thielman, the night shift people have taken the reins. Curtis can run 24-hours a day with two shifts and what they call the “continuous operations” people. They are the swing-shift people who take over the hot jobs that require 24-hour production. This group enables Curtis to keep overtime under control while not wearing out the operators over the year. It requires a lot of juggling by supervisors and operators to make this work, but Curtis has refined the process over many years. Tonight, two guys from night shift are attending a Union meeting, but Robin Johnson has everything under control. He has worked a variety of jobs at Curtis through his career, and relishes nights because he has less back up than he would on days — just the way he likes it. Nuara is having another ad hoc meeting with engineers. Carmichael and Krajewski are smiling their way around the plant, looking for glitches. The swarf is moving smoothly at the moment towards the big Mayfran spinner.

It’s starting to snow a little in Buffalo. What could be nicer? Bring it on.

1 Comment

Do any of you know where an operator can receive training for swiss turn machines in Erie PA?