I’d like to be able to say my health care adventure began when I was skiing in the Alps or rock climbing in Costa Rica, but the truth is not nearly as glamorous. I slipped on the ice while walking my dogs around the block on Christmas Eve day.

While I was falling everything went into that weird slow motion that precedes disaster, and I looked over at my left arm and saw it was awkwardly bent back. My hand was turned under, fi ngers pointing behind me and my palm up. I landed first on the top of my hand with the rest of me tumbling after.

Thus, like Alice down the rabbit hole, I was plunged instantly into the U.S. health care system bringing along a broken wrist, good insurance and much apprehension.

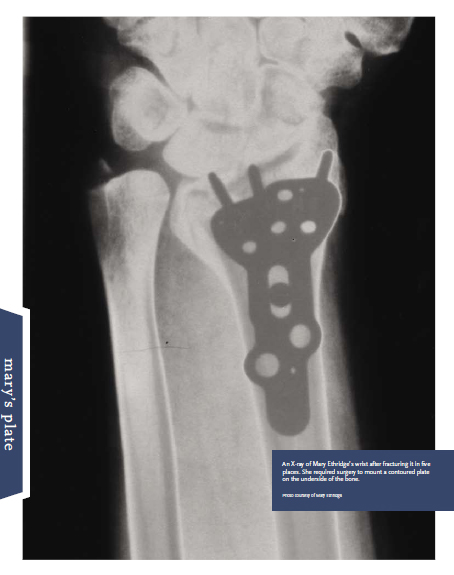

Fractures of the distal radius account for one-sixth of all emergency room visits, according to the American Hospital Association, but mine was an unusually bad break. My wrist was in five pieces and an ordinary cast wasn’t enough. The E.R. doctor told me I needed to see a specialist.

My insurance allows me to see any doctor I want, so I chose Akron-based Dr. John X. Biondi, said to be one of the best in northeast Ohio. I saw him the Monday after Christmas and spent that New Year’s Eve marveling at my brand new body part while I waited for the surgery. It is a contoured plate that sits on the underside (or volar side) of the bone. With the help of angled screws it holds the pieces of bone together so they heal.

America’s Broken System

With a broken wrist and lousy winter weather, I had a lot of time to watch television. Although I did see my share of Oprah and Dr. Phil, I found myself watching a lot about the efforts of politicians in Washington to reform our health care system. It is a system marked by ingenuity and skill, the kind that invented my plate and implanted it without complication. But it is also a system overrun with inefficiency and inequality, the sort that allowed me to have an operation out of reach of many others.

Total health care spending as a percentage of the GDP has nearly tripled in the last 40 years. There are more than 47 million people without health insurance in the country and millions more with inadequate coverage. As the recession drags on, the old employer-based system of health benefits is disintegrating faster than ever. Hospitals and doctors are already seeing a drop-off in patients as more people lose their insurance and put off elective procedures.

President Obama has promised to overhaul health care, but no one knows what form it will take. The uncertainty has almost fueled panic in the health care sector. The Dow Jones Medical Equipment Index fell 37 percent in 2008. Between November and December when the S&P 500 went down by about 9 percent the medical device index was down 18 percent.

What will be preserved and what will not? My broken wrist episode offered me an opportunity to take a closer look at the roles of the various stakeholders in health care. I found it akin to watching a parade through a fence, I could see it piece by piece but couldn’t grasp how the whole thing moves or behaves. Health care is not known for transparency.

“You Want to Know, What?”

“Usually people don’t take this much interest in their plates,” a receptionist at the surgeon’s office said when I asked if she knew where my plate had been made. She looked at me over the top of her reading glasses, just like my Dad used to when, as a teen, I’d pushed him too far. “I’ll have to check with the doctor, tell me why again you want to know this?”

A dozen or more people would ask me that question during the course of my information gathering. Wariness and weariness seem to have replaced confidence and optimism in the health care industry. It’s not really surprising given the current financial structure of health care in the United States. In the case of medical devices (such as my plate), selection, purchasing and reimbursement make their way from manufacturer to patient under the influence of various stakeholders, including hospital (or surgery center), supplier, physician, distributor, payer and patient. Each stakeholder has an agenda that is often in conflict with other stakeholders.

I began unraveling the story with the person who designed my plate. As it turned out, I didn’t have to go far, just downstairs from my surgeon’s office. The plate was designed by Dr. David B. Kay, a physician who, along with my surgeon and other doctors, owns the Crystal Clinic where I had my surgery.

Where My Plate Came From

I had stumbled by accident, literally, into one of many hot-button issues in health care—physician entrepreneurship. The United States has about 5,000 ambulatory service centers such as the Crystal Clinic. An ASC is a health care facility that specializes in providing surgery, including certain pain management and diagnostic services in an outpatient setting. They’ve seen steady growth since the first one opened in Phoenix in 1970. About 22 million procedures will be performed in the centers this year, up from 6 million in 1999, according to the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, a trade group in Alexandria, Va. Doctors own at least part of more than 90 percent of such centers in the United States. Physician ownership accounts for two-thirds of doctor-owned centers while joint ownership with hospitals, corporations or a combination make up the rest.

Using hundreds of CT scans of wrist bones, Dr. Kay and his biomedical engineering team came up with a composite model of a wrist and used CAD software to develop the OrthoHelix DR Lock—my new body part. They created a tool kit that holds not only three sizes of plates (short, standard and long) for both left and right wrists, but also 2.4 mm screws, 2.0 mm pegs and 3.5 mm locking and non-locking screws. The screws are blunt-tipped and partially tapered at the top to prevent tendon irritation and add strength. They also include color-coded tools, such as an angled screwdriver, designed to make implanting the plate as straightforward as possible.

The plate itself is a roughly T-shaped piece of 316 LVM stainless steel, curved slightly and studded with screw and pinholes. Kay chose stainless steel instead of the titanium common in other plates because it’s been shown to reduce the chances of irritation and tendon adhesion. “We had to accommodate a broad range of knowledge and surgical skills,” said Kay. “No doctor has or wants to spend a lot of time struggling to master the procedure.”

Surgeons pay only for the plate and screws they use from the kit and the rest is sent back to OrthoHelix for re-sterilization and re-use.

Derek Lewis, vice president of research and development for OrthoHelix, said the plate is about $1 worth of steel but estimates that they pay the manufacturer about $300 per plate.

“It’s easy for people to look at this and say it’s just a piece of metal. They don’t realize the millions of dollars that went into its development—the seven engineers who spent months working on it, the machine time it takes to produce it,” he said. “Then there are patents and liability issues that add to the cost. That’s what you’re paying for.”

Manufacturing Medical, Not an Easy Task

Once OrthoHelix came up with the design for the distal radius plate, they went seeking someone to produce it. The manufacturer had to be certified by the Food and Drug Administration and have sophisticated enough equipment to machine the intricate design. A microscopic f law could mean surgical failure, complications and potentially, fines and lawsuits.

They considered manufacturers in China but found that not only were there quality and turnaround concerns, but the price wasn’t much different.

“We need to tightly control and monitor the manufacturing of our devices. That would be a lot harder to do if it’s manufactured in China,” said Dr. Kay. “Any cost savings just aren’t worth it.”

OrthoHelix uses several manufacturers across the country for its various hand and foot implants. The distal radius lock plate is machined at RAM Medical Solutions LLC, a division of RAM Precision, a second generation family business in Dayton, Ohio.

President Rick Mount is the son of the company’s founder who started the business 35 years ago in the family garage. The company’s traditional base was food and beverage container manufacturing, but Mount felt that business was reaching its maturity and there wasn’t much room for growth. In contrast, sales of orthopedic implants rose an average of 9 percent annually over the past five years and are expected to reach more than $15 billion this year according to a study by the Freedonia Group, a Cleveland-based research company.

Mount started RAM Medical in 2002. It’s not an easy segment to enter, Mount said. First he had to earn FDA certification, a time and money consuming process.

He expanded his production capabilities with nearly $2 million in new machines. They include several Makino model S-56, 5-axis vertical machining centers with wireless touch probe and laser tool settings, 8- and 14-axis Swiss screw machines including a Citizen L20 Type VII 8-axis Swiss Screw machine with high pressure coolant and magazine bar feeder and Citizen M32 Y 24-axis Swiss with high pressure coolant and magazine bar feeder, and an Anca TX7 CNC tool and cutter grinder. He also enhanced his CMM capabilities with a Sheffield Endeavor CNC CMM, and a Micro-Vu Vertex Optical CNC video and touch probe measuring system. He bought two Vibra- Hone FSV-025 tumblers, new jig and rotary grinders and a 3-5-station nitric passivation system.

“What made this kind of investment sensible for us is that our employees already had the precision skills necessary to do medical machining,” he said. “The container side of our business is even more precise than the medical, so we already had the talent to handle it.”

Because the OrthoHelix distal radius plate is contoured and the holes are angled, machining them is a complex process with a cycle time of nearly two hours. Mount said it would take 12 different setups per side just to do the holes if it weren’t for his 5-axis CNC machines.

He said his company produces “hundreds if not thousands” of distal radius plates for OrthoHelix at a time. The number of machines used in a run depends on how quickly they need them.

Mount said it’s hard to say whether his profit margin has improved since he took on the medical business.

“Everything we make gets plowed back into the business. We’re always investing,” he said. But since the launch of RAM Medical, Mount has been able to add 10 new employees and a second shift. Medical contracts now account for 25 percent of his business.

So What’s the Bottom Line?

Neither Mount nor OrthoHelix was willing to reveal how much RAM Precision is paid for manufacturing the DR Lock plate. No one at the clinic was either able or willing to tell me what they paid for the plate, but Lewis of OrthoHelix said it usually runs between $800 and $1,800, depending on the size of the plate and screws.

Finding out what I was charged was a bit easier. The Crystal Clinic billed my insurance company $3,850 for the surgery, $1,727 of which was the cost of the implant. The rest was the surgeon’s fee, anesthesiology, operating room fee and medications. Insurance paid the clinic 63 percent of what it asked: $2,457 for the entire, of which $1,088.01 was for the implant.

My insurance company wouldn’t talk about how it negotiates with suppliers, but I asked a former colleague of mine in the industry if this was standard reimbursement. He declined to talk specifics, but offered me some insights.

“There is no such thing,” he said. “We negotiate differently with different providers. Some of them want to play hardball and others accept what we give. What we pay just depends partly on that.”

Reporter’s note: My wrist and I are well; our healthcare system remains broken.

2 Comments

Nice Article…

Actually, it sounds like your procedure and all went pretty well.

Seems like pretty advanced health care for less than $5000!

I not sure that’s the best example of how the system is broken.

I had spine surgery after a fall a few years ago and the total cost was over $100,000.

I only have complaints about the mess of dealing with the Insurance companies. The stack of paperwork my wife had to keep track of was over 3 inches thick; and we were still dealing with unpaid claims two years after surgery.

If we ran our company as inefficienty as that, we’d be out of business in less than a year.

So, yes, I agree that the Health Care System is in need of some sort of repair

My story did not have the same happy ending. Eight months ago, I had an ortho helix plate implanted in my foot. After surgery, I developed MSSA. It is May and I have now had three surgeries for debridment. I have been on various different antibiotics since the surgery, all to no avail. I will soon be having a fourth surgery to remove the hardware, which at this point seems to be the culprit. So, after many months of lost activity, countless medical bills, enormous amount of time lost from work and facing the consequences of long term antibiotic use, I am hopeful that the removal of the hardware will resolve this issue once and for all. Good luck to anyone that is facing a similar situation. I was a healthy person prior to receiving this implant.